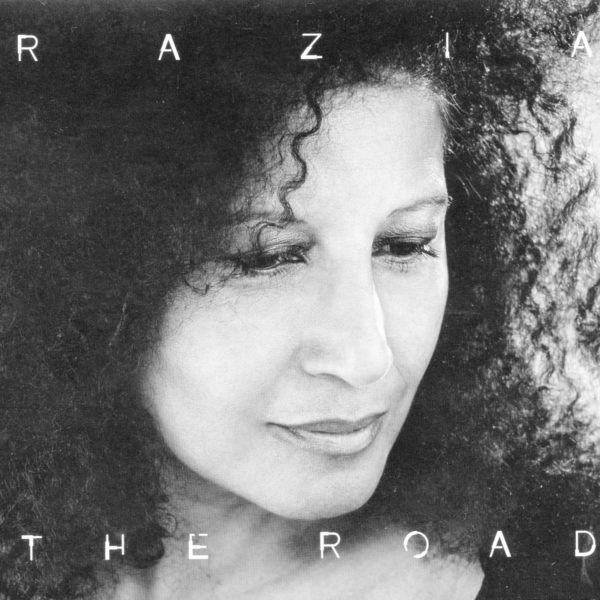

Razia Said was born in Antalaha, in the heart of vanilla country in northeast Madagascar. She has lived in many parts of the world, including Harlem, New York, which has been her base for some years now. Razia recently released her third album, The Road. It’s an unusual album, a departure from her earlier works in that it is more spare and intimate, and more personal. The album was conceived and essentially created in Antalaha, where she had returned to be with her ailing grandmother, Tombozandry. These days, Razia spends lives part time in St. Lucia. But Afropop’s Banning Eyre caught up with her on a recent stay in New York to discuss The Road. Here is their conversation.

Banning Eyre: Good to see you again, Razia. Tell me the story of how this album came to be.

Razia: The Road came to be like this. It was in September, 2016, I got a phone call saying that I had to rush to Madagascar because my grandmother was in bad shape. She was just about to turn 92 she was not feeling well. She was dying. So my aunt asked me to rush to Madagascar as my grandmother and I are very close and she wanted to see me before she went.

So, of course, I hop on the first plane. I remember I was moving from one place to another the day before, but I hopped on the plane and arrived in Madagascar. My grandmother was not at her best, and I thought she was going to go within a day or so. But eventually, seeing me I guess kind of resurrected her. And she ended up living another four months after that. But within about 10 days, we kind of realized that she was coming back to life. So I decided stay with her until the end. She needed me there, so I stayed.

Because I stayed there much longer than I expected, I decided, okay, this is the perfect time to channel all this energy in all these emotions into music. I'm in Madagascar after all. I had played before with the guitarist Raledy during the Wake Up Madagascar tour in 2014. We had spent some time on my terrace in Harlem playing some music together. And I remember with Jamie, my ex-husband, thinking that this would be a really good person to write music with. So I decided to call Raledy and see if he was available.

Tell us who Raledy is.

Raledy is this amazing guitar player from the northeast of Madagascar, from Anatsui exactly. He is a farmer when he's not performing. He's an amazing player. He has a band himself. He does salegy, he's one most important salegy guitar players. He has played with Jaojoby since years ago. And it seems like Jaojoby is having a hard time letting him go with me, just because he's such an amazing, amazing guitarist. But not only guitarist. He's just an amazing creative person.

So I got in touch with him, and he said, "Yeah, when you need me there?" Within 24 hours he was in Antalaha, and so was Harvey, from Surinam, the my drummer and the producer of the album. We decided that the three of us were going to lock ourselves in for a month and come up with some stuff. That was already a lot of music that I had written before, but some of the stuff, three songs, were really written on the spot. So we rented this place and we just stayed there for three months and worked from basically 9 to 5, sometimes 9 to 8—every day, and we came out with the music on The Road.

Did you set up a little recording studio in the apartment?

When Harvey got to town, he brought his little toys. We just had a small preamp and a computer with enough memory. I couldn't believe the stuff we got with just that. We had the microphone that I work with, a Neumann microphone. But that's all we had.

One microphone?

One microphone. And it’s really a microphone for performing live. It's not even recording microphone. We recorded most of the guitar tracks direct. I brought my guitar, this Gaudin that I really like. And I knew that Raledy really liked that guitar also. So he recorded just with that. We had the cajon, and a keyboard that we had bought in Antananarivo, something that was not too expensive. So that was the setup. And we were recording in the area in town close to the bazaar, the market. There was a tire shop right next to us. You could always hear clink, clink, clink! It was like, "Oh God, this is going to go on the recording."

But eventually, because the guitar was direct, it was fine. There was only one vocal from the recordings we did there, which was “Nave,” a salegy where we really wanted to have the atmosphere of the place. I had Raledy coaching me on how to sing salegy the way it's supposed to be sung.

That’s a sweet track, really uplifting.

Yes. And after we recorded it, we thought that even if we heard a little bit of “kong, kong, kong” from the tire shop, it's not a big deal. Because it was bringing some real atmosphere to the whole thing. But everything else after that we recorded here in Harlem, in the basement, with another Neumann microphone.

But the core spirit was captured there.

Yes. The whole thing was captured right there in Antalaha.

Tell me about the songs you are inspired to write there.

Well “Nave” we wrote there. And “Ayo” was written there. That's a song about my mother. Because my mother was there as well. My grandmother was not feeling good, so everyone came from all over the world. My mother, who usually lives in France, came to be beside my mother there, and I had my aunt there who raised me with my grandmother. I had my father, who doesn't speak with my mother. All these dynamics were going on within about one mile at most from where we were. So I wrote “Ayo” there, and “Lalagny Araiky,” which means “the only road.” That’s a song about the course of one’s life from childhood to death. And also “Remandreny,” a song of thanks to my grandmother, and really to all parents who raise children in uncertain times.

“Ayo” is interesting because you are singing to your mother, maybe even saying things in the song that you would not say to her in life—or things that would be harder to say.

Yes. I'm going deeper into expressing the feelings that I probably never got a chance to tell her. Because there was always this kind of block about being too expressive emotionally. We never got there. We got to the point where we say we loved each other, which was really good. That was before I got married. We had a discussion, and we got there. But other than that… you know, I still have actually to get her a copy of the CD, because she doesn't want to hear it.

Why not?

Oh, because it is coming from me.

Well, maybe she will get a surprise when she finally does hear it.

I know. I can't wait to have her really listen to it and pay attention to the words that I'm saying, which I think would make her feel good. But all these songs really came together while I was there. Also “Tsy Lany” about my grandmother, as I was seeing her disappearing. It's just saying that when you are so attached to somebody, to see them going, you don't want it to just end there. You can't believe that is just over. I felt like I had to write that song to say that love goes beyond. Whether you're there or you're not there, love just keeps going on—there’s kind of this infinity about the feeling of love.

One of your these uses a lot of proverbs.

Yes, that's “Filongoa.” That is a song from a person called Beanala. I really love his writing We did “Kajio” together, one of my favorite songs from the last album, Akory. We got together, and he said, "I have this sketch of a song. Let's work on it." And that became “Filongoa.” I thought it was a really good idea to use some proverbs from Madagascar that talk about friendship, and how alone you are much less than if you are in a group. I thought it was also appropriate, because we kind of created it all together. It was a good friendship song.

That's the song that Lionel Loueke plays guitar on.

Yes. What happened with this song is that we didn't have the time to put Raledy on it properly. When we were in Antalaha, we were living together, doing everything together. And I'm coming with this New York energy: "Okay, we’ve got a be efficient. There are some deadlines here. We've got to finish all the songs." [laughs]

And on top of that he wasn't used to eating like we do. “You guys, you put so much oil in your food." Because in Madagascar, we eat with no oil basically. Oil is expensive, and we don't put it in our food. So when you do the romazava, which is this dish made out of leaves, you can put some meat or fish in it, and the oil that is going to happen is what comes from that fish or meet. But I put olive oil everything I eat. So after a while, he was like, "I cannot take this oil anymore." It was really funny. So that was kind of the inside story of all this pressure that I was putting on working a certain number of hours a day, because I knew that we had very limited time. He had to go back. And then the food situation. It was very funny.

So “Filongoa” we didn't get to finish it. So for that song, we recorded Raledy in Antananarivo, because he had a gig there. We recorded him in a studio, but somehow, we didn't have the feeling anymore what we had in Antalaha, so we decided it didn't fit. Then when we came to New York, Harvey said, “Let me ask Lionel. I think he'd be great on this song. Let me contact him to see if he's going to do this.” Lionel is a friend of Harvey’s, so we contacted him, and he said sure. So we did it, and it gives a little bit of extra flavor. It's funny, because now the album is being looked at closely by the press in Madagascar. They are saying is has this "Pan African" thing, which is mostly given by Lionel’s playing, and also in “Mbola Velogno,” at the end where it turns into soukous, which is not Malagasy per se. So these are the two parts of West Africa that we borrowed with Fred Doumbe. Mamadou Ba plays the first part, of “Mbola Velogno” and it's Fred at the end. We think Fred is one of the best soukous players as far as bass playing goes.

Raledy is used to playing salegy. But you were encouraging, even pushing, him come to play things he was not used to. Talk about that.

That was part of the stress, because he was used to just going into the salegy. That's the natural thing for him. So he was saying, "I cannot do this. This is so complicated!" He would say "Maybe you should get a classical person." And I'd say, “No, this is the whole idea. We want you to do it. Using the salegy approach to this classical, or whatever you call it. He was calling it soul. “I'm not a soul player. I cannot play soul music.”

I would want arpeggios. And he would say, “I'm not used to arpeggios." And I would say, “Oh come on. It's going to be good. Try it. And after a retake he would say, "It's hard. It's hard. But it's beautiful.”

How do you think he felt at the end.

I think he was just glad it was over. “You got it? You got it? You happy?”

Thanks Razia. It’s a lovely album. You know, this story got me reflecting again on the way death is observed and processed by people in Madagascar. There are elaborate, multi-day funerals, remembrances rituals years later, including the famidihana, where an ancestor’s bones are removed from the family tomb, washed and rewrapped amid music, dancing and feasting. You don’t find rituals like this in many parts of the world. But it's a striking feature of spiritual life in Madagascar. Why do you think that is?

Why do I think that is? I never asked myself that question. But we are very much connected with this whole turning of the dead ritual. When people die, once they’re decomposed, we wait about 2 to 3 years, and then we wash the bones. We wash the bones and then rewrap them in cloth. And that is the time when they're totally free, and they can fly. Because all the time before that, they've been kind of imprisoned in their bodies. That passage, which happens with a sacrificing of zebus [cattle]. There’s a question of how many Zebus can you afford to kill? Because you have to feed the whole village, or five villages. Actually, we are going to do this for my grandmother. I think we will wait three years. That would be January, 2021.

Such a powerful ritual. And I know that the long tsapiky funerals held in the south of Madagascar involve a similar focus on ancestors. People drop everything and travel long distances to attend these events.

Yes. And the tombs in the South to have these beautiful sculptures and artwork. It's the passageway to eternity.

It seems like there's a special attachment to the land itself.

Oh yes. In Madagascar, the attachment to the land is powerful. Very powerful. Like they say, if you own a piece of land, you cannot sell it. I own a piece of land in Tamatava. And I've been thinking I'm not sure what I want to do with it because I don't think I'm going to live in Tamatava anytime soon. And my grandmother said, “But you cannot sell it. Because this is your land.” They say that wherever they buried your umbilical cord is where you're supposed to be buried as well. So like my umbilical cord is somewhere next to a river in Antalaha, and this is where I am expected to be buried.

So there is this a very powerful connection with the land in Madagascar. And I think that's why one of the president's big mistake has been selling land to Korean or Chinese companies. The whole of Madagascar just went completely berserk. “What? Selling our land?”

It’s the same way with the tavy, the slash and burn agriculture. It's something that we were raised with, and it's customary from way back. So it's very hard to make people understand that this is destroying Madagascar. That something that is so deep that even if we played it every day on television, every day on the radio, it's just hard to change these habits. I don't know what it will take. But it will take a lot.

Such a tough one. Sometimes you find situations where societies are wholesale throwing away tradition, and that is also terrible. As my friend Thomas Mapfumo has often said, you have to look at traditions and decide which ones to keep and which ones to abandon.

Exactly. You have to make a selection. Because sometime it's really been negative part of life, and it’s putting us in danger.

But I think those Malagasy traditions around death are socially healthy for the most part, because they bind communities together. I say that just to make a contrast with slash and burn.

Oh yes. I'm totally for those ancestor traditions. I'm not so happy about cutting the heads of the zebus with a machete… But there's also a lot of beautiful chanting that goes with these events, a lot of music. It's a magical time, very spiritual, very deep.

Well, we have gotten far away from your album. Madagascar music is so specific. This record has a lot of different influences in it, but it still has a strong Malagasy identity. People who love it are crazy about it. But it’s had a hard time finding a big audience here.

Yes, the rhythm of Malagasy music makes it a little bit difficult for people to digest. It is such a specific sound coming from there. Either you fall totally in love with it, or you don't get it. I see a lot of my friends who play other kinds of music, music from Mali, music from Senegal. Somehow, it’s easier for the Western public to digest those sounds. Madagascar music remains a little bit hidden. Like Madagascar is.

I think it has to do with history. The reason that music from Mali and Senegal is easier for us to get is that we’re connected those places through history. That's where so many of the African-Americans came from.

That is true. But we're trying. We can only do what we love to do, and hope that it breaks through. Maybe on the next album I should do a little more English. I love to write in English. That could be one way.

You have just spent a couple of months are promoting this album with live concerts. How's that gone?

It's going pretty well. When people actually get to the shows and hear the music, they love it. There's been a generally positive reaction. They love the introduction of jazzy things in it. Bringing the strings and people love it.

You have a cello in your live ensemble.

Yes, and upright bass, violin. So we’re looking at the future. I don't think it's something's just related to me personally. The future of the music in general. It has to be this kind of multimedia thing. That’s why we are working on videos for these songs. This is what really resonates. People react to that. So it's challenging. But I like challenges.

Well, it’s a beautiful album, and we look forward to those videos.

Yes. They are coming.

Thanks so much, Razia

Thank you.

Related Audio Programs

Related Articles