The following is excerpted from interviews with University of KwaZulu Natal lecturers Sazi Dlamini and Kathryn Olsen, and SABC veteran Welcome Nzimande. Note that the speakers use the terms maskanda and maskandi pretty much interchangeably. Sometimes maskanda describes the music, and maskandi the musicians, but the usages are not always consistent with that. These excerpts come from interviews conducted by Afropop’s Banning Eyre in Durban, South Africa, in January 2019.

SAZI DLAMINI is a lecturer, but also a musician who has recorded with his group Skokiane.

Maskanda’s Beginnings

Maskanda is now recognized as a style of music. The term itself comes from Afrikaans word, musikant, which is “musician.” Before it crystallized into describing Zulu musicians, it meant anyone who played an instrument. For example, in Johannesburg's urban milieu of swing and jazz, musicians who worked the streets at night and got stopped by police had to prove that they were musicians to the police, and this was often by playing on their instruments—saxophones and trumpets—before they could get their ID stamped to say: “O.K., you are a musikant and you can go your way for the night.”

But with the consolidation of ethnic groupings, there was a push to define black South Africans according to their ethnicity—there was ethnic radio, and so on—there was a lot invested in creating an idea of independent cultures. And "maskanda" came to describe Zulu traditional music played on instruments.

Maskanda was originally a solo style, solo musicians playing their street music on concertina or guitar in the countryside, or in hostels with the men singing. But they disappeared quite quickly, and so with production, the style got orchestrated into ensembles in emulation of mqashiyo, a style of mbaqanga that followed the jazz era in the 1960s.

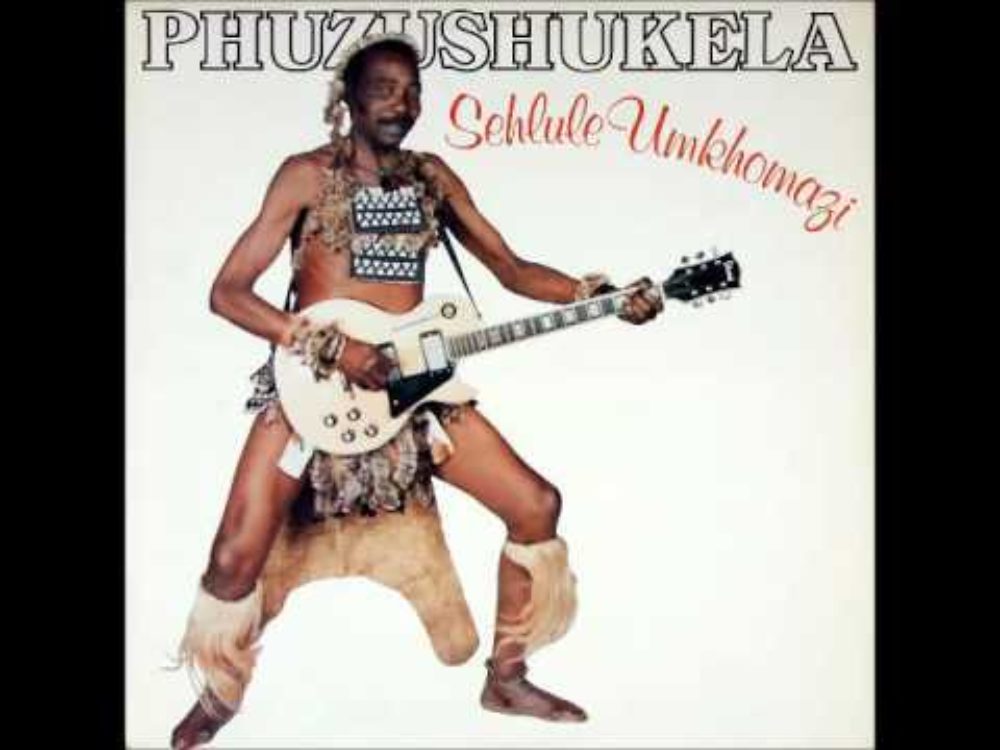

Phuzushukela (1930-1982)

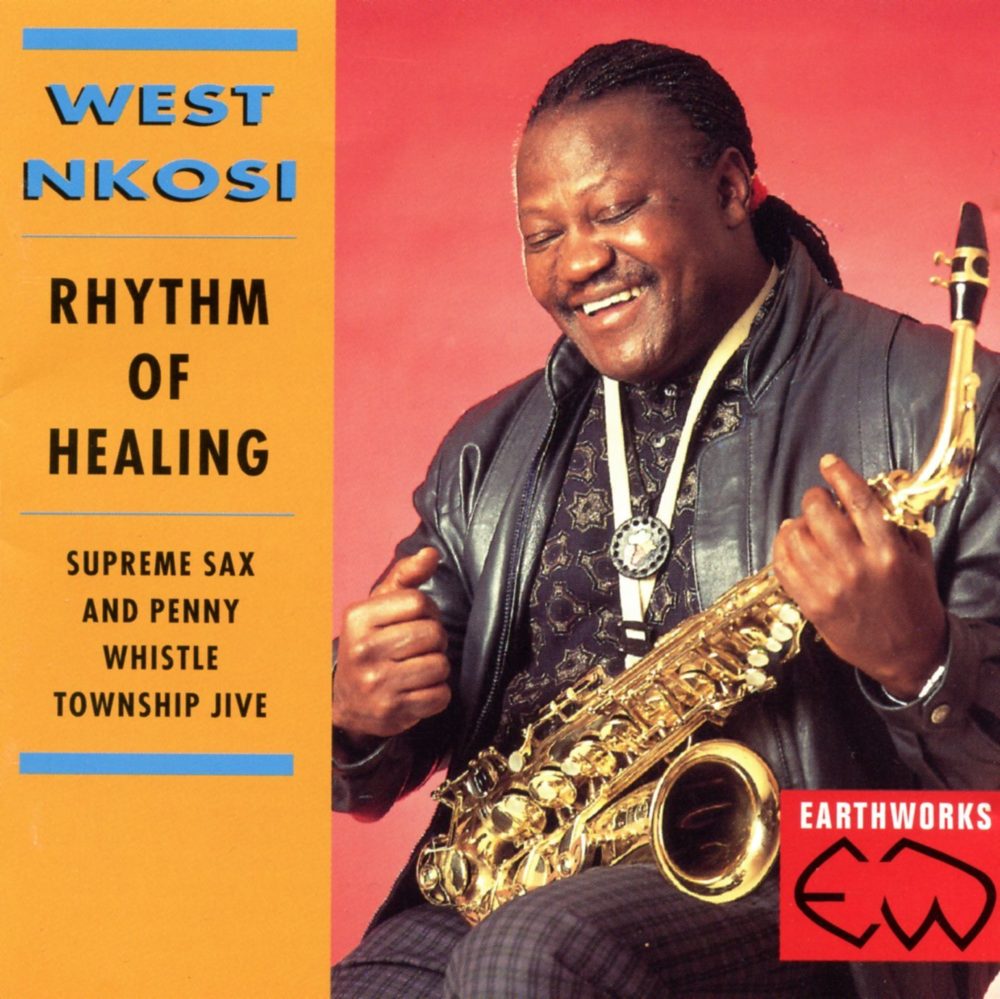

Mqashiyo was kind of hot in the early '60s when the likes of Phuzushukela—that's the earliest maskandi guitarist—were discovered. His real name was John Bengu. He was from Nkandla in Zululand, but he was working in Johannesburg, and so when they started recording, mqashiyo producers wanted to emulate the power and popularity of mbaqanga, so they came with bass, drums and backing vocals. West Nkosi and his contemporaries' producers were responsible for this, and it was very much embraced by the early ethnic radio. So they sang in Zulu and it got categorized as maskanda. I would say that only came about in the early '70s.

But imagine the early maskanda musicians being open to tradition on one side—the migrant workers with indigenous traditions—and then urban listeners raised on school culture, church culture and Western music. There is certainly a distinction in the forms of music, not only in structure, but in terms of the harmonic sound. For example, Western popular music is defined by cadential, diatonic I-IV-V harmony. Traditional harmony is often based on alternating fundamental roots, just a second apart, or a minor third apart, as in mouth-bow music, just fundamental notes. But of course how it’s structured between leading voice and chorus makes for quite a complex sound.

Some of the newer forms of maskanda draw more from Western contemporary styles. There’s a name for that, shiyameni. It's the name of the river dividing Natal-- Colonial Natal and Zululand Natal, as early colonial structuring divided society. Some people ended up on the colonial side working on farms, and often running from being ostracized. They did not want to be identified as traditional. So they changed even the dances, their way of singing and shiyameni is one of the styles that came out of that.

Zulu Guitar

Pretty much as soon as Europeans arrived, they brought portable instruments like guitars, concertinas, harmonicas, accordions. These are as old as the encounter. Not everyone who picked up those instruments was traditional. There were other ways of playing Zulu guitar, African guitar. They were outside of tradition even then, taking on more Western influences and forms, urbanizing styles.

Maskanda itself changed. It wasn't a picking style at first. It was strumming. But when production began, and recording, the doyen guitarist, Phuzushukela, started to pick. Even he started small. His early recordings, especially the solo ones, did not have a lot of introduction, not the elaborate ukapika that has come to characterize maskanda. Just one line. Nor did they have the elaborate praises in them.

Maskanda Today

In commercial terms, as a trending sound, maskandi have disappeared, because they are not recognized or appreciated. We are talking more about nationally recorded broadcast phenomena. But maskandi playing is kind of a national thing. There are still a lot of maskandi who are unrecorded and play in the shade, in the old way. This morning someone was phoning me down from south coast and saying, "Hey, Dlamini, there's a young man here who is about to put away his guitar. And he is a very good maskanda player. What can you do?" Because he was expecting me to have some ways of promoting him, showing him what to do with his thing.

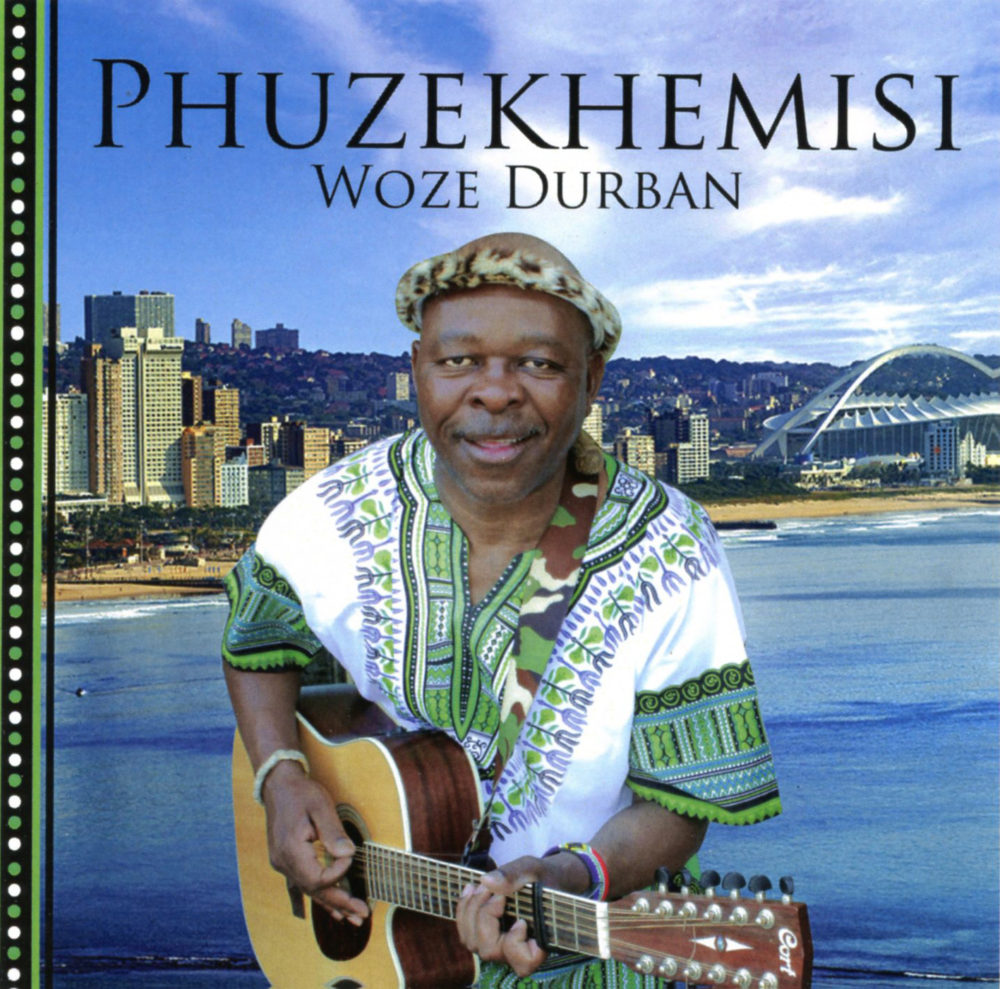

I suppose people have been misled into thinking culture is there for fame. If you play well, you deserve to be like Phuzekhemisi, you deserve to be rich. Whereas, like I say, it's something that you play with your family, around a fire or when you're going to see your friends.

A lot of maskanda is being recorded now. Don't get me wrong. There's still guitar, but it's not so much in the tradition of maskanda. It's very influenced by popular styles like soul and hip-hop.

Shiyani Ngcobo

Shiyani is very important to me in his appreciation and preservation of some of maskanda’s original forms and sensibilities. He was among the earliest contestants in a kind of competition that was looking to revive maskanda. It was sponsored by a brewer, a sorghum brewer. And it was a collaboration between radio broadcasting, and a kind of ethnomusicology initiative.

Of course, the recording industry was another partner, aside from sponsorship, that was putting a recording as one of the prizes. But the competition attracted a lot of grassroots participation, solitary maskandi artists. Shiyani comes from that wave, that very early wave. And he won. He was supposed to go and record ahead of Phuzekemisi. They come from the same part of the south coast. But Shiyani fell ill. He had to spend time in hospital, by which time I think there had already been two rounds of competition that put on the pedestal, on the limelight, Phuzekhemisi and Mfaz’Omnyama, among the most leading maskandi, so he remained unproduced and unrecorded [until 2003].

And also, I suppose he had much more opportunity to develop as an original maskandi, a solo maskandi, by which time there was enough interest to want to find the roots of maskanda and to remember it as a solo art. And so he became appreciated as a maskandi near the end of his life.

Phuzekhemisi

For a good decade, maskanda was just an ethnic music played on one station, the Zulu station. But then, towards the 1980s, in the mid-'80s, the resistance movement, especially the worker movement, was trying to draw on popular imagination. And they started engaging popular traditions like maskanda. So among Phuzekhemisi’s earliest outdoor concerts were for COSASTU, the Congress of South African Trade Unions. So he came in the most integrative phase of maskanda, where it was becoming relevant in the broader struggle, and also may be, in a way, filling in the cracks between tradition and modernity. That was the time when maskanda was becoming nationalized in a way. Its power was drawn to express a certain patriotism, beyond Zuluness.

[Note: Phuzekhemisi has produced 20 wonderful maskanda albums, and he did perform once in New York as part of Carnegie Hall’s South African Music Festival in 2005. When Afropop met him at the time, he told us that his name “was derived because I was working and not allowed to drink at work. I used to hide my beer at the chemist, at the pharmacy. So it means ‘the one who drinks at the chemist.’”

Phuzekhemisi also told us about his breakthrough song “Imbizo,” produced by West Nkosi in 1990. “It’s about the traditional leaders who were calling people and asking for money before the ANC was banned. So I was complaining about that. Every time they call on us to pay money, and we don't know what that money is going to. That's what made this one successful. And the song made them to dub me "The People's Voice," because I sing about the plight of the people in the rural areas, how they are struggling.”

Unfortunately, in 2018, Phuzekhemisi got caught up in the violence surrounding maskanda, and has faced a charge of murder.]

Maskanda’s Messages

Maskandi have never been overly political in their texts. More egalitarian, popular, talking about the plight of men generally, the position of women. Not protesting, but actually just pleading for things to stay as they are. A man is a big man, and better if he has more wives. And I don't think it helped that maskanda became nurtured within an institution of the radio that sought to assert the similarity of ethnicities.

A lot of maskanda practice and expression seems not to be fully aware, or to grasp, what the rest of humanity is about. That's why they fight. You know, they are misogynistic in their approaches, and often express views that are kind of backwards. They are great, but when you listen, the issues, you know, they are not penetrating into the issues of the day.

The kind of production that maskanda used was an imposed structure. They dared not to criticize anything. They were relying on being broadcast on national radio. But I must qualify that by saying that Shiyani [Ngcobo], who was never commercially produced, was very outspoken about issues that touched him. His lyrics were always to the point. Governance. Corruption of officials. AIDS. Social behavior. Very, very penetrating. He was never subject to production censorship of any kind. He spoke things as he saw them and felt them.

Maskanda Violence

The taxis play a lot of maskanda. In the taxi industry, one of the forms of patronage is certainly music. The contemporary big names in maskanda aren't necessarily close to the traditional aesthetic. Some of them have taxis on the road and enter the fray, running the passenger routes. They have to arm themselves. They have to be violent. Fearsome.

BHODLOZA "WELCOME" NZIMANDE is a longtime player in South African pop, a broadcaster of many years at the South Africa Broadcasting Corporation, who has been honored with a doctoral degree. Welcome is very proud of his achievements and has strong opinions on many subjects!

Isicathamiya and Maskanda

I am the guy that started working with the SABC in 1978, in August. I am a teacher by profession. When I started, I was just like everybody else who was interested in the international kind of music, from the colleges in the high schools. I thought this was the thing that was going to be good for us. But when I came to the SABC, Ukozi FM—during the time, it was Radio Zulu—my mind changed. I said, “But this is a Zulu station and we are not playing Zulu music.” I thought this was something funny.

I said, before blaming myself or blaming anybody, let me take an initiative of moving forward with this. I started focusing on maskandi, which is the traditional music, and isicathamiya [Zulu a cappella choral music]. They gave me isicathamiya, they felt it was the music that was good for my voice. I had to play artists like Ladysmith Black Mambazo. I promoted Black Mambazo extensively.

In isicathamiya, we had Empangeni Home Tigers, the King Star Brothers… They were the first, even before Mambazo. Oh, they were very good. But they didn’t go to the commercial side of it. They were merely on the starting side when the SABC were recording, not commercialized versions. It was just unfortunate. And we had Solomon Linda, this guy who came up with “Mbube,” which was translated as “Wimoweh” overseas. We had many isicathamiya acts. They were quite popular at the time, and they were promoted by an announcer in Johannesburg called Alexis Buthelezi. He is no more now, but he was very good at promoting them. I was still at school when I was listening to that isicathamiya program at night, starting from 10 or 11 o’clock at night.

Maskanda Production and Promotion

West Nkosi produced a lot of those early maskanda records. He was good. He was damn good. I remember when we started Phuzekhemisi no Khetani. He is the one that was very good producing those guys. And I still remember that. Because these guys came to me and said, “We are struggling. What can we do?” And I connected them with West Nkosi. But unfortunately, this other guy Khetani died. It was a car crash.

But when I started with maskandi, it was not popular. In fact, I was derided by my colleagues at the radio station. This is 1970s and coming into the '80s, and they were deriding me. Those who are still alive, they still say it today. “Hey, we were deriding you when you are playing these things, but we didn’t know was going to be this big.”

I promoted isicathamiya. I remember, we had a program on Radio Zulu. We had some competitions in different genres, isicathamiya, mbaqanga... Maskanda was not featuring at all. And then there was like Brenda's [Fassie] kind of pop music. Then one day, the powers that be of the SABC, of Radio Zulu, felt it was important that we also feature maskanda, because I had started promoting maskandi In 1982. So by roundabout 1984, they were starting to feature maskanda. It still didn't do that well, but it was coming.

You’ll find Black Mambazo comes up number one. I remember a guy who went overseas and he came back and he said he had a concept of Black Mambazo there. This rhythm: [hums in the manor of Ladysmith]. People fell in love with it overseas. They couldn't even know the meaning of what was said, but they fell in love with it. And I told Black Mambazo, "You are going to go overseas one day.” And Joseph Shabalala laughed at me. He said, "No. Who are we to go overseas?"

Then Paul Simon showed up after two years. I still remember. There were going to Germany. [Sings in German] They were practicing German now! And I even said, “It's not very important for the language. It's the rhythm that is important. If they hear what you're singing, they fall in love with it.” So we were proceeding very well with Black Mambazo at that time, because it was traditional music, and they were really making some marks.

But I still pushed on with maskanda. I wanted to find a strategy to promote it. Because most of the people, even our people in the rural areas, they didn't like it. They didn't like it. It's the stigma. Being uneducated. “You are useless people.” And they didn't fall in love with that. And I said, "O.K., I must have a strategy." And so I said, "This is the year of maskandi." Because I know if you say this is the year of something, people start listening. They started listening, and they started watching. And I started saying to the maskandi artists, “Raise the bar. Try and come up with things that are going to be interesting to the fans who are going to be following you."

And I spoke to the fans as well. “Try and love your people. Look, the best guitar that this guy is coming up with.” I started analyzing the lyrics themselves, and I started promoting that. Then we started with the gold discs. I remember in 1982 in August, we had two artists got the gold disk for the first time. That was Nganeziyamfisa and Khambalomvaleliso, and then Mzikayifani Buthelezi. They got the gold discs for the first time as maskandi artists. In 1987, we came up with SATMA, the South African Traditional Music Association. Joseph Shabalala was with us in that.

Then in 1989, we gave a chance to the ladies. I said to the ladies, "This is an opportunity. I hear now the boys are singing about their guys.” You see, a guy that has got a small voice would sing… [Sings high “Oh, my love.”] You are saying, “my boyfriend." A boy is saying "my boyfriend." And I said, it must be a lady that says that. Ladies, now you must take your place, and sing maskanda. There are maskanda musicians now like Izingane Zoma, Imithente and many others that have come on board. I pushed until it happened. In 1992, they were there, and really competing with the guys, up to this day

Maskanda Boasting

These guys sing, and they also talk. It’s called izibongo. They talk about their places. “I am so-and-so. I come from wherever. My king is so-and-so…" And all those things. By the way, they were nearly disqualified by the SABC when they started to do that. The powers that be felt that they were promoting themselves. “They are advertising themselves. They have to pay!” And I came in. I intervened and I said, "I'm happy that you have called me, because you would have done the wrong thing. These guys are doing it this way. It is natural for them in their tradition to talk about their indunas, their kings and their chiefs, to talk of their mountains and their homes. If you are going to stop them doing that, you're going to be killing their creativity.” They really listened to me and they let it go.

Then Stimela [the late guitarist/singer Ray Phiri’s band] came up and they also did that. They sang and called their mountains and all those things, and then the SABC started saying, "No, but these are not maskandi. These are merely promoting. They’re advertising!” Then they disqualified them, and Stimela did not continue with that.

Maskanda Unity

[Note: There is a history of intense, even violent, competition among commercial maskanda musicians and their fans.]

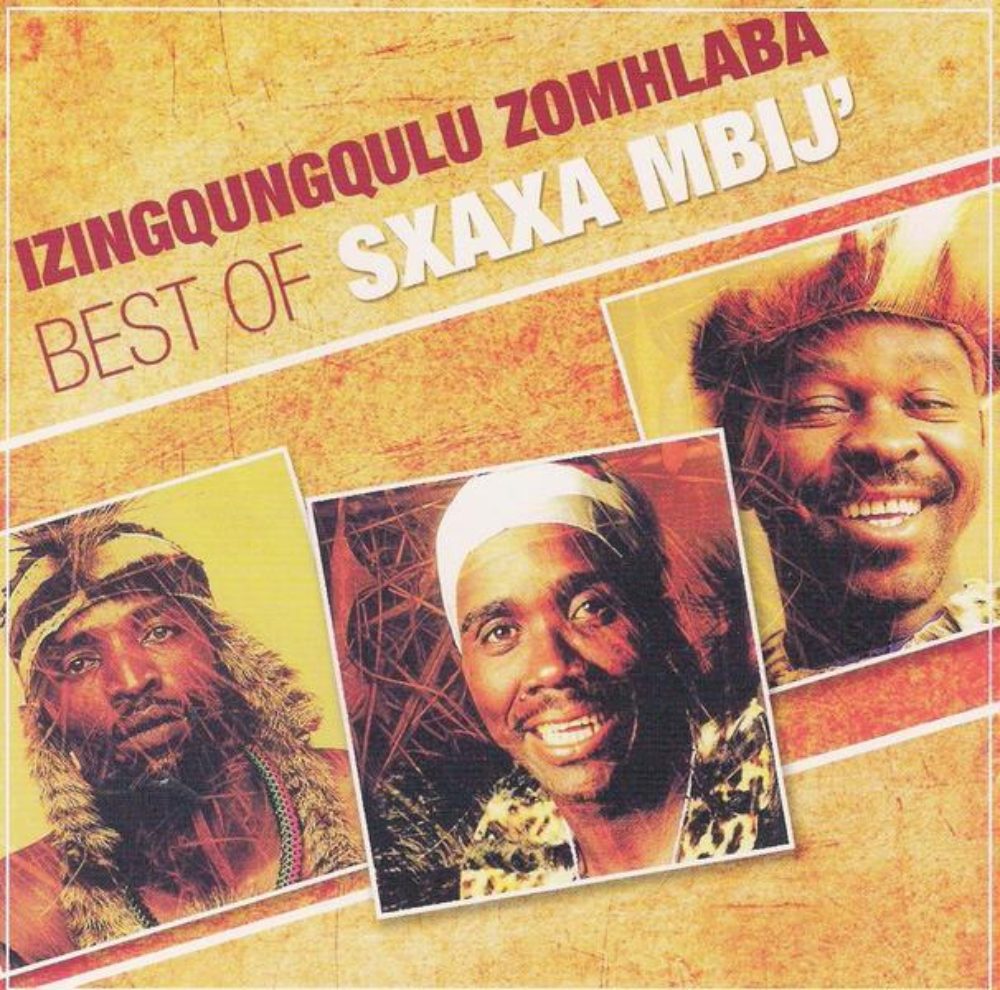

I used to bring some of the people together, especially because some of them were competing in a way that I didn’t like. In 1997, I brought in iHashi ‘Elimhlophe, Phuzekhemisi and Mfaz’ Onyama. I brought them together because they were doing different genres and because I felt they were coming on the right way. I wanted them to sing together, to play as a team. And I said to them, "Each must have four songs, 12 in all." I gave them the name Izingqungqulu Zomhlaba. It means “The Leaders of the World.” They came up with different songs, but the one I chose to lead the album was “Sxaxa Mbij’,” “Pull Together.” When the guys are working in the mines, they say, "Sxaxa Mbij’, Sxaxa Mbij’, Sxaxa Mbij’…” And it worked. Because you get some of the artists now, there are some of those who are also coming together.

I always push for that to try and make a situation where, if the people are quarreling, they can come together, and talk. First of all. And then start singing together. I was trying to say, "Away with what you are doing. Come together." Because you see, if you are fighting, there are followers, there are fans, and they start saying, "We are going to kill that one." And the news was coming to me that they wanted to kill Phuzekhemisi, because he was quarreling with Mfaz’ Onyama. So the best thing was to make those people come together and sing.

I brought them into the station, and I said, "Stop this. Otherwise I will stop playing you here on the station.” And some others forged ahead, and I said, "I am stopping you." And I stopped them. They came back and apologized. They said, "We are sorry. We can see the value of the station. What we have started is not helping us. We are no longer going to do it."

But the time when I left the SABC, they started coming back to doing that again. And why are they doing that? They say that the strategy works that way. They form the fans. You see, it's like the political parties, or the fans of soccer. The fans side with a team. They side with a party. So they are forming parties, and I said, "It is wrong. You must stop it because it is killing people, your fans.” There were people in hospitals because they went to the stadium and they were beaten because they were following the others. It's not like in soccer. In soccer, they really make noise, but they don't fight. “Now you can also try to come up with a strategy that's not going to make your people fight.

Today, they are having these factions between Ikoghama Elisha and Khuzani. And I met both of them towards the end of last year. I want them to perform together. They must talk to their people. “Now if you're going to kill your fans, this is not what I've taught you to do.” When it comes to festivals especially, they tell their fans in the social network, on Facebook. When they're going to have those festivals, they really talk, and they come together in numbers.

I still criticize it up to this day. I would love to see maskanda capturing most if not all the black people. It's their thing. I have said that on radio. I have said that on television. If these people are doing it in their language, their mother language, the mother tongue of those people, surely, they should be able to say, "This is our thing." And be proud. I was telling them about Michael Jackson overseas. Michael Jackson has taken most of these people that he was aiming to get, even here in South Africa. He got everybody. You see, we've got many people that could be like that. But the behavior of these musicians is what I am working on. The fighting. You can't do that if you want the respect of the people

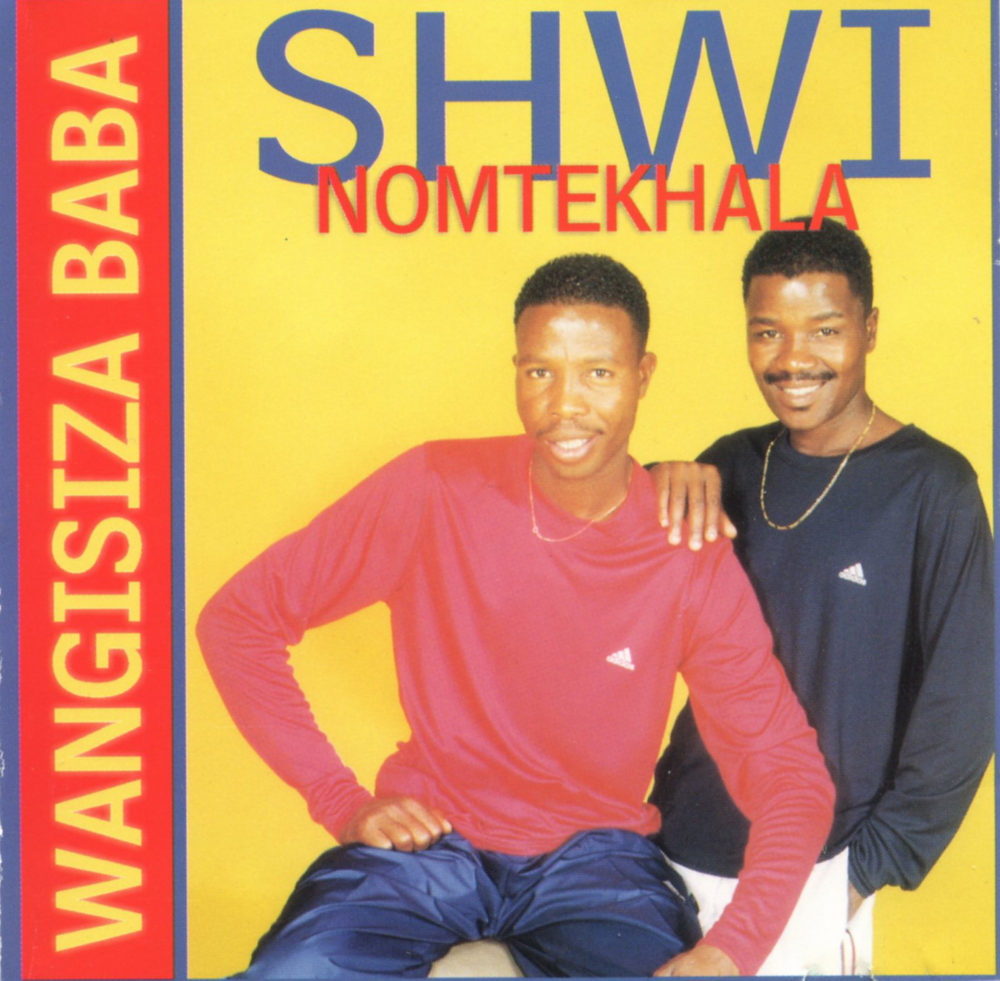

Shwi NoMtekhala

The other artist that became very popular in this country, still very popular, is Shwi NoMtekhala. They started singing this a cappella music, isicathamiya, following on the steps of the Black Mambazo as well. And I was saying to them, “Guys, why now changing?” And they said, “It works for us.” And I said, “Have you left isicathamiya?” And they said, “No, we have not left it. We still do it.”

But they took the side of the maskandi, and the thing that impressed me was the sales. The sales were close to 1 million on the side of maskanda. [Sings “Ngafa”] That’s the one that killed the nation. It really killed. One million, and there’s no artist that does that. “Ngafa,” being killed by AIDS. And it really sank into the minds of the people, the way AIDS was killing people. And it sold like… I don't remember any one artist that has sold more than that. Even in pop. Brenda Fassie never sold like that. Never.

The Future of Maskanda

The future is big, but it depends how we manage, how we lead, how we present it. It depends on the creativity as well, because innovation is key in everything that we do. Come up with something that you feel you're going to get and catch the interest of the people as an audience. If you come with that, then you are going to be succeeding. It's important that we stick to the leading trends as well. You see, like it comes to this social media. It is leading us somewhere.

I remember when I was still at SABC, they had a policy here that said we must speak pure Zulu language. “Don't speak other languages. Don't mix with other languages like English and all that." And I said, "We've made a research, and we are following the trends. And this is what we have come up with.” The people are leaving us, especially the youth, which is the majority." We must speak their language, the street language.

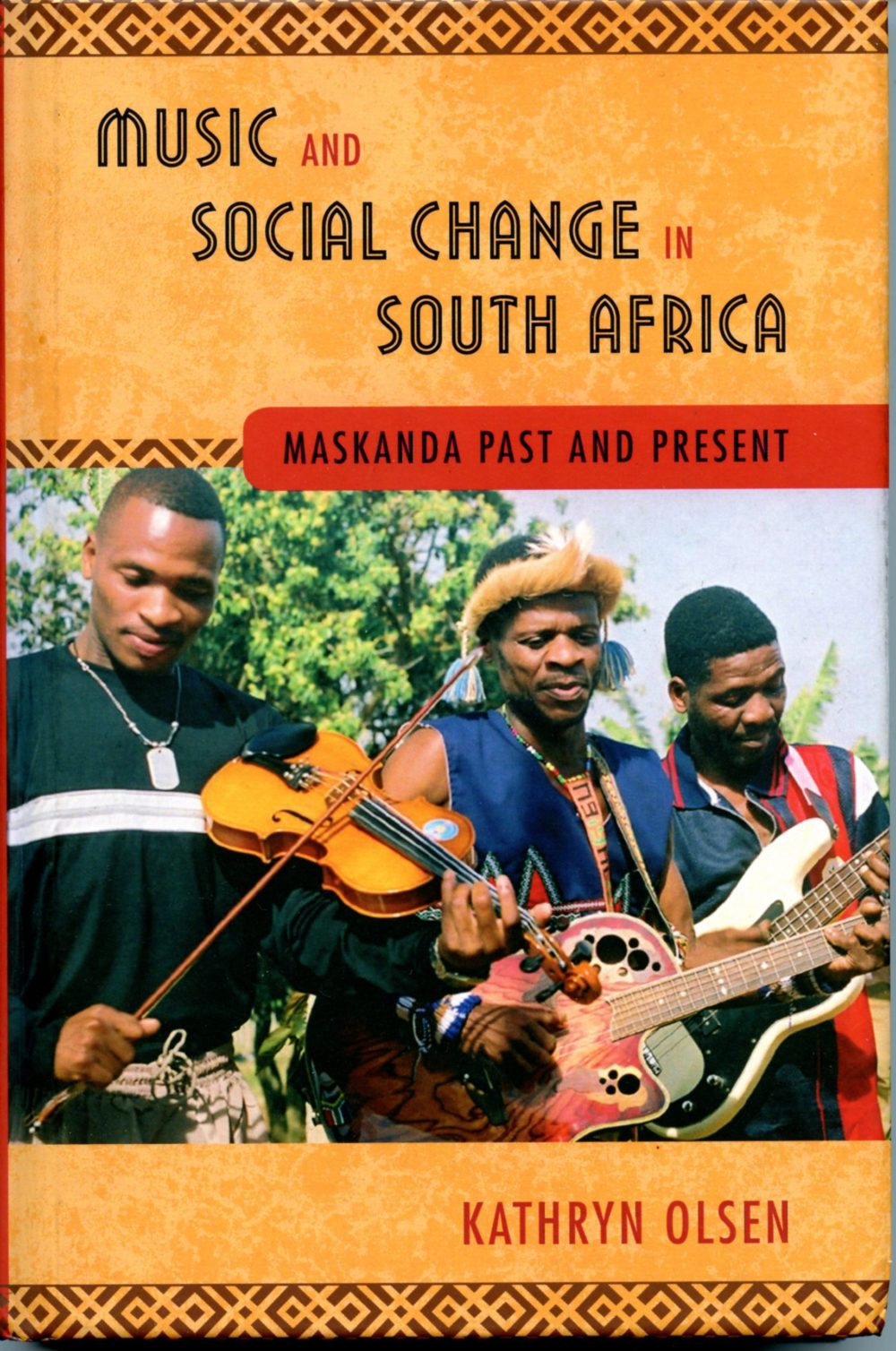

KATHRYN OLSEN completed her doctorate looking at maskanda music and its relationship to politics and social change. Her 2014 book, Music and Social Change in South Africa: Maskanda Past and Present, explores maskanda as a commentary on what was happening in South Africa during the late 1990s and up to 2008.

Researching Maskanda

It's quite a complicated thing, because infiltrating the maskanda domain, particularly for me as a white South African, and a woman, or as a foreigner, there is a significant amount of suspicion about what your motivations are. And I think that underlying everything, the issue is that people will ask you, "What is in this for me? How is this going to promote my career?” and ultimately, “How is it going to increase my bank account?" That has really become the bottom line with maskanda music.

I believe that maskanda has been sectionalized. You get those who are still maskanda musicians, who have some kind of musical aesthetic that they're trying to reproduce, something that they want to say, not just in lyrics, but also in the sound structures that they use. They are few and far between, but there tend to be little pockets of people who are doing that.

These are not people you might identify through studios or records. They are musicians who are playing maskanda music because that's what they do in their spare time. But their jobs are other jobs. And those are the musicians that I have a fundamental interest in. So I would say there is still the roots music, music that is not entirely motivated by some commercial intention.

But honestly, in my everyday experience, I don't come across maskanda musicians like you used to. Certainly, when I was growing up, and even in my early years of study, you would see street musicians everywhere. Very often people would be walking around and they had a guitar strapped to their back. No. You don't see that.

I don't think I can claim to be an authority, because I don't walk around the township all the time. I go there and work and I come out. But certainly in my encounters with township life, it’s gqom music that's the thing. It's not maskanda. If I look at my students, and I talk to them all the time, all those youngsters that come to study music, I ask them, "What about maskanda?” “No, that’s old people's music.

Underlying everything at the moment in South Africa, whether you are a musician or just anybody, is an economy that is just completely distraught. Nothing is working. Everything is falling apart. People don't have work. They don't have money. The place that everyone still imagines, from way back, to be the place of opportunity, is Egoli. That is Johannesburg. So people will go to Johannesburg to find work, and they will do any work

You have to make a living, and there are certain kinds of economic drivers that are going to determine how your musical style evolves. If you want to make a living out of music, you have to be aware of that kind of aesthetic. At the same time, we are encapsulated by a quick-fix ideology. I spend a fair amount of time up in northern KwaZulu Natal in a small place called Mutu. There, I get crowded by youngsters who will come with a computer. They don't come with their guitar. It's all computerized. And they want a record deal. I don't know where they get that idea. I don't have anything to do with a record deal, but it's like you are the person who can make it happen. “Just do it. Now.”

The last time I was there, I was so disturbed because I had youngsters who said to me, "I will leave school and I will come to Durban." They have no idea of how this would work. There's no real perception of: "I'm going to get my education and have a job." There is no opportunity; 90 percent of people don't get a job. They can even get a degree and they don't get job. Things are bad. The economy is desperate

Maskanda Origins

We don't really know how it came from musikant to maskanda. Some people say, “Well, you had to have a Zulu name.” So they just as Zulu-ized this word musikant to maskanda. That may well have happened, but we don't really know. There are a lot of myths surrounding maskanda and the early icons like Phuzushukela. In his very early recordings, where he's just playing with his guitar, it sounds like he sitting on the pavement playing, and someone has recorded it. These are very different to what you would get later on, what's recorded in the studio.

The stories about Phuzushukela and how he invented the ukapika style of guitar that's associated with maskanda, I don't think that’s completely true. I think that it was a bigger thing. Other people were doing that. There were people coming from Zimbabwe playing guitar, and emulating the sound of the mbira. So it had that more picking sound. I don't think it was just one man who came up with this idea. But that's been the fantasy that's been perpetuated over and over again. And now it's like truth. When my students, when I get them to write about it. They will say, "No. It's fact. It's what people have said."

Shwi NoMtekhala

Welcome was talking about Shwi NoMtekhala, which is a duet. And it's quite usual to have a duet. It is usually a lead singer and backup singers. So you've got a duet, and they both sing and play. And why we say that the singing draws on isicathamiya, is that their harmonies are directly related to that. So it has this kind of sweet sound that you associate with that, but with the guitar, which is more like Western folk music. It's strumming. It doesn't sound like maskanda to me. They don't do izibongo where you say where you come from and all that, which was really the stamp that distinguished maskanda from mbaqanga—that izibongo section. And the introductory guitar section where they really set the stage with the guitar, drawing you in: "Here I am. This is my location and I’ll move from there." A lot of that is gone. It is not seen as necessary, because they see and imitate the format of other types of commercially viable music, so, “Why do that? I don't need to do that.”

Phuzekhemisi still does it, but he has shrunk his izihlabo, which is the beginning, and izibongo, quite significantly. Shwi is sweet and comfortable. He'll talk about AIDS, but it's in a way that is not too challenging. What was significant at that time was you didn't mention the word AIDS, so at least they were mentioning it. So many of the artists, so many of the students and the people I worked with, have died of AIDS, and for many of them, and for many, many years, it was absolutely never, ever mentioned. It would be insulting if you said you recognize that they had AIDS.

Shwi did a DVD where he's definitely trying to reinvent the location of maskanda in the rural space. So we have what looks like a picnic site actually, with a little rondavel [traditional thatched hut]. It's all clean. There are no animals, no chickens, no snotty nosed children and dogs and goats. I look at it and I think it is so symbolic of where we are at. Because we are making it up as we go along in a desperate attempt to find something that's going to capture the market. So we will give you all these images that you already know, even though it's completely decontextualized and has no lived experience. It's an idealized, sanitized space, just a romantic idea.

iHashi ‘Elimhlophe

iHashi ‘Elimhlophe means “the white horse.” He is open, direct, an easy person to deal with. He has his own studio. He is a performer, and he has an amazing maskanda group. And he does promote younger musicians as well. He’s the same generation as the people that Welcome was talking about, like Phuzekhemisi. I think he was born in the 1960s.

iHashi is originally from KwaZulu-Natal, Greytown area, and he actually didn't start off as a maskanda artist. He started off doing mbaqanga, a Soul Brothers type of thing, and he moved from there into maskanda. But he does it his own way. He takes the izibongo way of delivering your vocals, which is rapidly spoken words, but he makes it into a kind of virtuosic rap. And he has expanded it into a bigger section in a lot of his songs. So it's capitalizing on the idea of rap music, but maskanda-izing it by having it spoken so fast and having the guitars way in the background. He's got big sections like that, and the crowds go wild for it. I go wild for it. I think it's amazing.

He’ll have songs during election times where he's talking about political parties and what people are doing and that kind of thing. Or he'll be talking about relationships or AIDS or “can't get a job, the economy’s over.” That sort of thing. He is not saying, “This is where I come from, but he's using that framework to punch out very topical issues.

He also presents himself as what I call the designer Zulu. Beautiful clothing. Not the stuff off the street, but using that format, the pants that have got different patterns all over them, but made by designers. And he has good sound engineers so that he produces a really nice product. It's like your upper-middle-class, urban person who feels that it makes them feel significantly South African. It’s not just trying to be a replica of something from overseas.

So his audience is more elite, more educated. Whereas maskanda, traditionally, has always been seen as the music of the common working man. Not the person who had any kind of education. So there was a distinction. Isicathamiya was for amakorwa, which is people who had missionary education. And maskanda was for the bottom-end laborer who had nothing. And there is still that kind of stigma. If you are a maskanda musician, you are from the backend of nowhere, really. What do you know?

I work with iHashi ‘Elimhlophe, and we have a very good relationship, and with his wife and his kids. He has made money. He is an entrepreneur. He doesn't want anything from me. And I think what happens when you try to investigate, people want something from you, but you've got nothing to give them.

Phuzekhemisi

Phuzekhemisi is an interesting person because he also had an eye to the market and tried to manipulate his music and record things that incorporated different influences. But it has never really worked for him. He has to stick to his thing, and it lands up where he says, "My audience feels betrayed when I try to do that. They don't like it." It's like you have superimposed one thing on the other. But the interesting thing, going back to I’Hashi, when he does things like incorporating gospel into maskanda, he does it in such a way that it melds together and produces something new. But Phuzekhemisi can't break out. It's too late for him to be a transitional figure.

Johnny Clegg

You know, Johnny Clegg revealed a potential that may be, from a bigger ideological position, a kind of coming together. It's not maskanda, his music. But he uses maskanda. There are strong influences in there, and the rhythms particularly are embedded in it, but he has reformulated it into quite a different sound. It's like Busi Mhlongo. She also has strong maskanda elements in the music. But people don't know what to call it. It's not maskanda. There's something more jazzy.

What I love about what Johnny Clegg did—and I don't know him well; I have only met him a couple of times—is that as an anthropologist he buried himself in Zulu culture, and I think he had a strong understanding of what it meant to be Zulu in a different era, the '50s and '60s maybe, that kind of Zulu-ness.

Also, Johnny Clegg did some really nice papers on the different dance styles and the rhythms and the beats, and also the harmonies. The connection between the makoyana bow and the guitar playing. The bi-tonal nature of the makoyana bow and how it translated onto the guitar. And you can hear that in some of the music that Shiyani played, when he used that little tin guitar, the igogogo. Because of the way he tuned it, it sounded more like a makoyana bow because of the resonances of the strings, but also because of the way he tuned and played it. So it had a kind of connection to the past in ways that the ordinary guitar doesn't have.

Introducing Shiyani Ngcobo (2004 CD)

The story was that Ben Mandelson came here to visit [anthropologist] Angela Impey. They had met elsewhere, and he came to visit her, and I said to them, “There is this amazing musician, Shiyani Ngcobo and his accompanist Aaron Meyiwa. They play as a duo that just blows me away.” And he said, "Oh, let’s get them together.” So they all came to my house, and he recorded a demo at the house. That led to the album. And they came here to record that as well.

But the interesting thing with that CD is that, here, they wouldn't play it on the radio. They played a little bit on SAFM, which is like a black middle-class radio station. But they wouldn't play it on Ukhosi FM. They wouldn't give him a slot. They said it was from overseas. It was not in their stables. And also there was a lot of resistance to the way it was recorded. It wasn't bass heavy. It was featuring the guitar.

People would listen to it and say, "Well, it's not really Zulu." It was not really Zulu probably because it didn’t have the bass-heavy and drum-heavy combination that gives maskanda a certain kind of drive, a sound that links it to ngoma dance, which is your big warlike music. It doesn't have that.

This is where it becomes tricky, because you can't really tell other people from other cultures what you think is happening with their music. But I see that drumming as actually a distortion. Because if you experience ngoma dancing in the township, or in the rural areas just performed by people, you don't have that. It's singing, and you do have the stomp. But it's not that thundering sound, that constant whacking of the drum kit. I see that as the Westernization, making it commercially viable. I'm not saying that's a bad thing. But I don't think that's its Zulu element.

Female Maskanda

Welcome was talking about “the ladies,” and how he encouraged them. I have very strong views about that and about those artists he mentioned, Imithente and Izingane Zoma. Imithente has an interesting split because they have got the one style which is more like the commercial music, talking about love and all that. And then they have the other set of CDs that are much more spiritual, and drawing on older styles. It's slower and it's got the harmonies that you get when you're singing old songs to the ancestors. It uses a kind of trumpet-like sound to be reminiscent of the Shembe Church. So it's got this different element which is drawing on traditional religion as opposed to gospel, which is the Christian thing.

Now Izingane Zoma is another female group. All the music is written by men. They are singers. They don't compose the music. They are brought in and they perform the music and it's now said to be female maskanda. Well, I think that's a bit of a joke. Because they are just doing as you do in a patriarchal society, doing what the men tell you to do.

When I tried to interview them a long time ago, I couldn't interview them without an intermediary from the studio. And they weren't allowed to answer my questions directly. I had to speak through him. And very soon, my interpreter told me that what I was asking wasn't being asked. So I just lost interest in the whole process. But they don't have a voice, those women. They are toys of the industry. That's my view.

[Kathryn notes that it’s a different story for female musicians outside the world of maskanda.]

Many of them are very powerful and irreverent. There's one Latoya Buthelezi. She’s Mangosutu Buthelezi’s granddaughter. [She goes by the stage name Toya Delazy.] She is this gay performer, very powerful and outspoken, a really divine woman. So she comes from a history of the king of ethnic nationalism, but his granddaughter is basically saying, "I do it my way." I love her. She's an exciting woman. But I have yet to find a maskanda group of women who are their own drivers.

Zulu Identity

Where I differ significantly from what Welcome says is that maskanda is still hugely politicized. There is still a strong claim that is essentially Zulu music, even though Xhosa people and Sotho people can play maskanda, they will say, in a kind of patronizing way, "Yes, they can play maskanda." But there is an undercurrent of “You have never authentically really got it unless you are steeped in Zulu culture.

Whenever I spend a lot of time in Johannesburg and work there, I'm very aware of how different it is there, as opposed to being in Durban. In KwaZulu-Natal, there is a strong sense that you are in the territory of the Zulu people. They own it. They decide what happens. It's a very Zulu-ized place. In Johannesburg, it's much more multicultural. People mix more freely. There isn't that ethnic consciousness.

But even on campus here, students come and they are Xhosa or Sotho. We have a lot of Zimbabwean students. The Zulu students tell them, "You know, you are not in your place. This is our place.” Jacob Zuma is the same story—that whole entourage of support that he has is because of his Zulu-ness. That's my view.

Competition and Violence

There have been artists set one against the other. They have this kind of duel and in the songs they badmouth the other person, and then they get a response, and it builds this anxiety and tension.

You know, Welcome claims that he is going to speak to these musicians and get them to stop the violence. I think he might actually be able to do something. Certainly no one else would. He has the credibility. People really do look up to him, and I think he’s got a kind heart. The thing is, things have changed so that whereas you would have looked up to the chief, now you might look up to the chief, but you fear the nganga, the witch doctor, and you fear the gang warlords, the people who got the power and the money to annihilate you.

Related Audio Programs

Related Articles