Thandiswa Mazwai has lived the modern history of African music. In the early ‘90s, when she was still a teenager, she pioneered the emerging kwaito sound in South Africa, first with a trio called Jack-Knife, and then as the lead vocalist and composer for Bongo Maffin. Thandiswa’s 2004 debut album as a solo artist, Zabalaza, went double platinum and established her as a major star. Since then, she has delved into jazz, rock, classic African pop styles, and more. Her latest release, Sankofa, is an expansive and moody set of eleven tracks interweaving traditional field recordings of Xhosa music in rich and varied sonic tableaus. There are even songs recorded in Senegal, with traditional West African sounds in the mix. It’s the culmination of a singular, genre-bending career.

Afropop’s Banning Eyre spoke with Thandiswa twice this year, once before her performance at globalFEST in New York in January, and once more recently following the release of Sankofa. This transcript merges the two conversations.

Thandiswa is currently back in the United States for two shows at the Crystal Ballroom in Boston (November 13) and Le Poisson Rouge in New York (November 14).

Banning Eyre: Thandiswa! So good to see you. What have you been up to? I saw that you did a show recently with the rock band Blk Jks. That’s new territory for you, isn’t it?

Thandiswa Mazwai: Well, over the years I've messed around with a lot of different things. I've done some jazz. I've done some punk stuff. I did a couple of gigs with the Blk Jks. Every now and then, we get bored in Joburg, and we realize we should create these alternative spaces, spaces for a little bit more transgression.

And now you have this new album.

It has about 10 years between projects and problems. Now that I'm getting older, I'm realizing I don't have all that time. So I might move a little faster. I'm definitely going to start working a lot faster. Right now, I've just recorded this album called Sankofa that mixes a lot of jazz with some traditional South African music elements. The album is really eclectic. It was produced by Meshell Ndegeocello, and then some of it was produced by South African pianist Nduduzo Makhathini, who's a dear friend of mine. I've been working on it for about a year and a half now because I do take my time.

Before we get to the album, let me ask about music in South Africa. My impression is that music styles change very fast there.

Yes. Particularly since apartheid. It's really taken on a life of its own. I mean the whole trajectory between kwaito and gqom and amapiano and all these things.

And now, this is happening in the context of Nigeria taking over the global music scene. How do you reflect on all that? What do you think about South Africa's place in today’s global music?

I actually think that South Africa is probably the most important place on the continent in terms of music and culture, because what happens in South Africa then morphs and everybody else on the continent begins to follow. I think there's a particular energy that comes from South Africa that you can't find anywhere else, and it's very infectious on the rest of the continent. Everyone now is doing amapiano, you know? Chris Brown is doing amapiano.

So it's interesting that this tiny little corner of the earth... What's the word in English? This unassuming little corner of Pretoria? That’s where a lot of partying happens, but you don't want to go to Pretoria. It's not one of those places you say, “When I go to South Africa, I want to go to Pretoria.” But because of that, I think Pretoria develops this culture that is completely uninhibited and uninformed by all these other things. Joburg can be much more informed by international influences, you know.

So this is why Pretoria has produced a lot of these modern sounds, right?

Yes. Pretoria insists on being itself and only itself. It doesn't try to be cosmopolitan. Pretoria remains in this world of its own. And I think that's the beauty of it, and that's the interesting thing about it. This little corner in the world, much like Jamaica, for instance, with reggae and dancehall, managed to seep into the psyches and the consciousness of people all over the world.

It's interesting that gqom has been able to do that. But also, the thing about South Africa is how varied the music industry is. There's a very vibrant dance music scene, and then there's a vibrant jazz scene, and a vibrant pop scene where the music could be played anywhere in the world, like Tyla, for instance.

Absolutely.

Then there are other, small alternative musics that exist in South Africa. So I think that that's the interesting thing about it, is how varied it can be.

So true. We felt that way even way back in the late ‘80s when we first went to South Africa. There was a broader, more diversified music market than anywhere else we’d been in Africa.

You can't expect one thing. As much as you can see Mahotela Queens, it would not be the same as Miriam Makeba, and would be very different from Hugh Masekela.

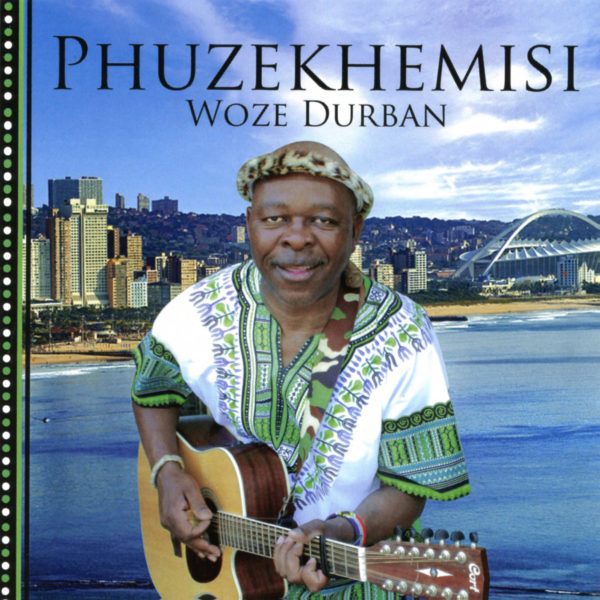

I play guitar and I'm a big fan of maskanda, and I gather that Zulu guitar style continues, right?

Yes, maskanda continues. I mean, we have always merged maskanda into our work. There's no way you can escape that Zulu guitar. The way that they pick that guitar, there's no way you can escape that when you are a South African musician.

On our first visit, we interviewed Johnny Clegg and he taught me a few of those maskanda riffs and I still play them. They're hypnotizing, almost therapeutic, you know?

Absolutely.

Unfortunately, very little of that particular music has ever made it to these shores.

Yes, that's unfortunate, but it exists anyway. It exists. It exists.

It’s interesting that even with this whole panorama of music that you have in South Africa, somehow it all feels like South African music.

Yes, you can pick it out. When someone says it's South African music you, really have to expect anything. I never know exactly how to analyze it, but when I hear it, I think, “Okay, that's from South Africa.” I try not to analyze it because then I might look for it. I might want to intentionally do it, you know?.

What do you write songs about?

I would love to write about frivolous things. I would love to write about a walk in town eating ice cream, and a lot of times I try, but to no avail. I do write about love, but it's love of my country, love of my people, love of my culture, all these things that are in danger. I don't live in a place of safety. So, yes, I do write about love, but it always has this touch of something political. I write a lot about pain and rage and love and dissatisfaction. Someone said they feel that a lot of my work is about dissatisfaction.

Dissatisfaction.

Because I was born in 1976, which was a very powerful year in the struggle for our freedom. And so I also have a very, very real memory of apartheid, but I also have a very real memory of the euphoria of when freedom came in 1990, 1992. And then I also have a lived experience of the disappointment, the dissatisfaction, the dream deferred. I am very much obsessed with memory and identity and freedom. These are my obsessions. I can't escape them in my work.

There’s a tension between music as an escape from troubles and music as a tool for awakening consciousness. I've talked to a lot of Nigerian artists about this because Nigeria has got as many problems as South Africa. But most of the singers steer away from that. They adopt the name Afrobeats, a nod to Fela Kuti, but very few of them follow in his example when it comes to messages.

Yeah, maybe that's how they put the “s” at the end. Sometimes I wish that as a Black artist or as an African artist I had the ease to think of something else or to just dream and do whatever comes to mind. In many ways I do, but it's a luxury. It's a luxury that comes with ease and without such ease you are really in the struggle for your life.

I spent a lot of time in Zimbabwe in the 90s especially. I wrote a book about Thomas Mapfumo.

Yes, one of my favorites!

Me too. He's my man. But I remember the time before the end of apartheid. He was listening to a lot of South African music and he was critical of artists for not being political enough. This was in the ‘80s. But I wonder if the more pop-oriented South African artists today experience this tension.

Absolutely. What goes on in South African music, or creative spaces, it's sort of hit and miss. For instance, the version of amapiano that arrives to the world is quite a sterilized version. Then there's a version of amapiano that lives in South Africa and only in South Africa that requires the geography, the emotion, the energy, the rage, the desperation. All of that is required.

The kids of amapiano, they do as they please. They remind me very much of us as young, kwaito kids where the music didn't seem like it was political, but in its joy and in its exuberance and even in its kind of wildness and craziness, it was representing a moment in South African history, and I think that's what amapiano does now. It represents that dissatisfaction, that dream deferred. Its joyfulness is almost an act of defiance. There's an act of defiance but there's also a madness there. The kids are drinking a lot of this thing called savannah, which is a cider that they put on their heads when they are dancing. It’s a recklessness that comes from not wanting to be tied down, feeling boggled down by the state, and the corruption, and the lack of service delivery when you're living in the ghettos of South Africa. Then this kind of madness erupts.

That's very interesting. Is it a matter of the words they use in songs?

Yeah, but it's also the hardness of the amapiano. The amapiano you get here is soft, it's sterilized, it's gentle. The amapiano in the ghetto is rugged, it's grungy. There's nothing clean about it at all. Half the time they don't even have lyrics, they're just making sounds. It's just emotion. And it makes so much sense to us when we listen, when we hear that sound, something lights up in us. It only happens in South Africa.

Let’s talk about the new album. I read that it began during COVID, when you went to Rhodes University and began listening to field recordings from the International Library of African Music in Grahamstown. These are recordings made by Hugh and Andrew Tracey. Tell me about those recordings you heard and how they inspired you to lead to this album.

Yes. So Rhodes University has this huge archive of recordings from all over the continent. In 2009, they gave me access to field recordings of traditional Xhosa music, which I kind of pocketed away and forgot about for a while. And then somehow, during COVID, I stumbled over them again, and this time, they kind of made sense to me. I knew exactly what I wanted to do with them. So the album was really responding to that archive.

At first, it was myself and my bass player, Tendai Shoko. We were listening and figuring out what we wanted to say, how we wanted to wrap ourselves around these songs. We started chopping them up and sampling them and reversing them and making them faster and all these different things that you can do with samples. We started building worlds around them. And then once we had a couple of ideas, just by chance, I was chatting with Meshell Ndegeocello, and she said, “So what are you working on?” She said, “Send something.” And I sent it. And she loved it and said, “Let's make an album.” That's kind of how it started.

Wow. That's beautiful. Talk about your process with Meshell. How did that work?

Well, you know, I sent her the demos. There were maybe about four at the time. Then in May of 2022, we had our first sessions in New York. I wanted us to have these workshop sessions before the recordings, you know? So I was like, “Let's workshop them so I can see what you're thinking.” And she was just like, “No, we know what we're going to do. We're just going to do it.” She is a very, very, very sure kind of producer. I worked with a couple of people on this album, and she was very certain about what she would bring to it.

So we had an intensive two days and we recorded three songs. It was just really incredible, the lineup of musicians she brought into the studio, like Deantoni Parks on drums, Chris Bruce on guitar, Tarus Mateen on bass. He plays with Jason Moran on The Bandwagon. Then we had a young pianist, Julius Rodriguez. It was just a really incredible lineup of musicians who came to kind of interpret our demos and respond to this archive.

And then you worked with this wonderful jazz artist, Ndududzo Makhathini. How did he get involved?

Well, after the sessions with Meshell, I came home and I was wondering what to do next. I had always wanted to go to West Africa and record music with the kora and the ngoni, the talking drum. My previous manager, who passed away during COVID, was arranging this because he was also managing Salif Keita. I was supposed to go to Salif Keita’s Studio Moffou, but that didn't work out. And so I was sitting there thinking: how else am I going to make this work? And then I got a little eureka moment. I called Ndududzo and said, “Hey, we have some demos. Do you want to come with us to Senegal and make this work with me?” It happened very easily and very quickly. We flew to Senegal. I called a friend of mine, Mohammed Fall, who was born and raised in Senegal. “Can you put this together?” So Mohammed basically brought us some of the best musicians available in Dakar. And we did the same thing, you know, throw these demos at them and say, “Insert yourself. Respond to this archive.” And obviously, with Nduduzo as my producer, we were able to really get the best out of it.

I spotted those West African instruments right away. Tell me about one of the songs you recorded in Dakar, the song “Dogon.”

Well, it's one of my favorite places in the world. I traveled to Mali for the first time in 2009, and we went everywhere, we went to Bamako, to Djenne and Segu, and we also went to Dogon. We were trying to get to the Festival in the Desert. But when we went to Dogon it was such an incredible experience. When we arrived there, we met this family that graciously gave us their rooftop to sleep on. They make beds for travelers on their rooftops. So we spent the night on this beautiful rooftop under the stars in Dogon. And then the next day we trekked up the mountain to see the ruins of the old settlements.

We really experienced quite deeply the traditions of Dogon, and the story of their origin and how they could draw the map to Sirius B, or Po Tolo, before Western scientists had created a telescope that could see that far. So Dogon for me becomes part of the mythology of African origin, of ritual, and also about our knowledge of the stars, and so many other things, medicine, science, astronomy. So I insert that song to evoke that ancient knowledge.

You know, South Africa, being the last country on the African continent to get its independence, was very much closed off to what was happening in the rest of Africa. African history is something that's very much alien to a lot of young South Africans or people who grew up in my generation. We had to go and find this information ourselves. It wasn't readily available.

The other song you recorded in Dakar is “Children of the Soil,” which is a beautiful kind of ambient piece with that 12/8 pulse that I always associate with this part of Africa. Tell me about that song.

I guess I would say, having been born during apartheid South Africa, I have this obsession with my pan-African identity because a big part of our struggle for freedom was our struggle to reconnect with the rest of Africa again. And so the song “Children of the Soil” is to pay homage to all the beautiful children from all over the continent. We have a song that says, “From Cape to Cairo, from Morocco to Madagascar, this is home.” So this is a song that reminds us of our beauty, of our greatness, of our history of empire and the immense and beautiful possibilities that exist in our present and in our future. It's about placing myself back into the African continent and then reimagining myself into really beautiful futures. These are my creative obsessions.

Well, you're not alone. Afrofuturism, that connection between the future and the ancient past, is huge these days.

It's a beautiful, interesting, complex thing of joining the past and the future. Because a lot of what colonialism did is about erasure. So the work of freeing yourself, or decolonizing the mind, is to reimagine yourself into this world.

You spoke earlier about dissatisfaction. I feel that in the song “Emini.”

Yes. “Emini” is very much about that dissatisfaction, that voice of public dissent. There's another one too, called “Kunzima Dark Side,” the dark side of the rainbow. South Africa has often been called the rainbow nation. It creates this false narrative that everything is all fluffy clouds and unicorns. But there's something that's always been festering. And it erupts every now and then and reminds us that this is very much a dream deferred. In many ways, we thought that because someone who looks like me is inside that parliament, then they will act on my behalf. And the past 30 years have very violently proven to us that this is not true. And we find ourselves in this nightmarish position of being in the struggle yet again.

There are two parts to that song. I hear the mouthbow in the beginning, and we alternate between a march-like rhythm and then this sparse, out-of-rhythm section. I can feel that darkness in both.

Yes. The music speaks to the rage of having to be in the same place, the horror, the dissatisfaction, the sadness. There's an incredible Brazilian word, saudade. The dictionary says it means this longing for something or someone whose whereabouts are unknown.

But it's deeper than that, isn't it?

It's like a deep nostalgia for something or someone that you might never find. For me, the state of being a South African is this saudade, this deep sadness, this deep longing.

I guess that comes from the experience of having so much hope and such belief that the world had fundamentally changed, and then finding that it hasn't actually changed that much.

Absolutely. I was 18 years old when we first voted, and this was the first time anyone in my family got an ID, which means this was the first time we became South African citizens. So there was definitely a euphoria. It felt like yesterday you were not free, and today you are. For a second, really believed in this idea of Madiba's magic. We used to speak about it all the time. You know, if our soccer team would win, they would say it was Madiba magic. So we all kind of believed in this idea that Madiba and Winnie Mandela would wave this magic wand and things would change. But once Mandela and Winnie Mandela separated as a couple, we realized that something is rotten in the state.

I mentioned that I wrote a book about Thomas Mapfumo. His experience with the Mugabe era had a similar trajectory. And his songs tell the story.

Actually, Thomas Mapfumo was someone I listened to a lot just before making this album. I kind of went back to his work. You know, those guitars!

Yes, those guitars are what seduced me in the beginning. But then getting to know him and the history of Zimbabwe and the meanings in those songs took me to another level.

I would say that every album I make has artists that sit with me while I'm making the album, and for this this one I would say that definitely Thomas Mapfumo was one of them.

That's interesting. Let's talk about the style of these songs. When I listen to “Emini,” it reminds me of the techno Zulu music that Busi Mhlonga was doing at one point in her career.

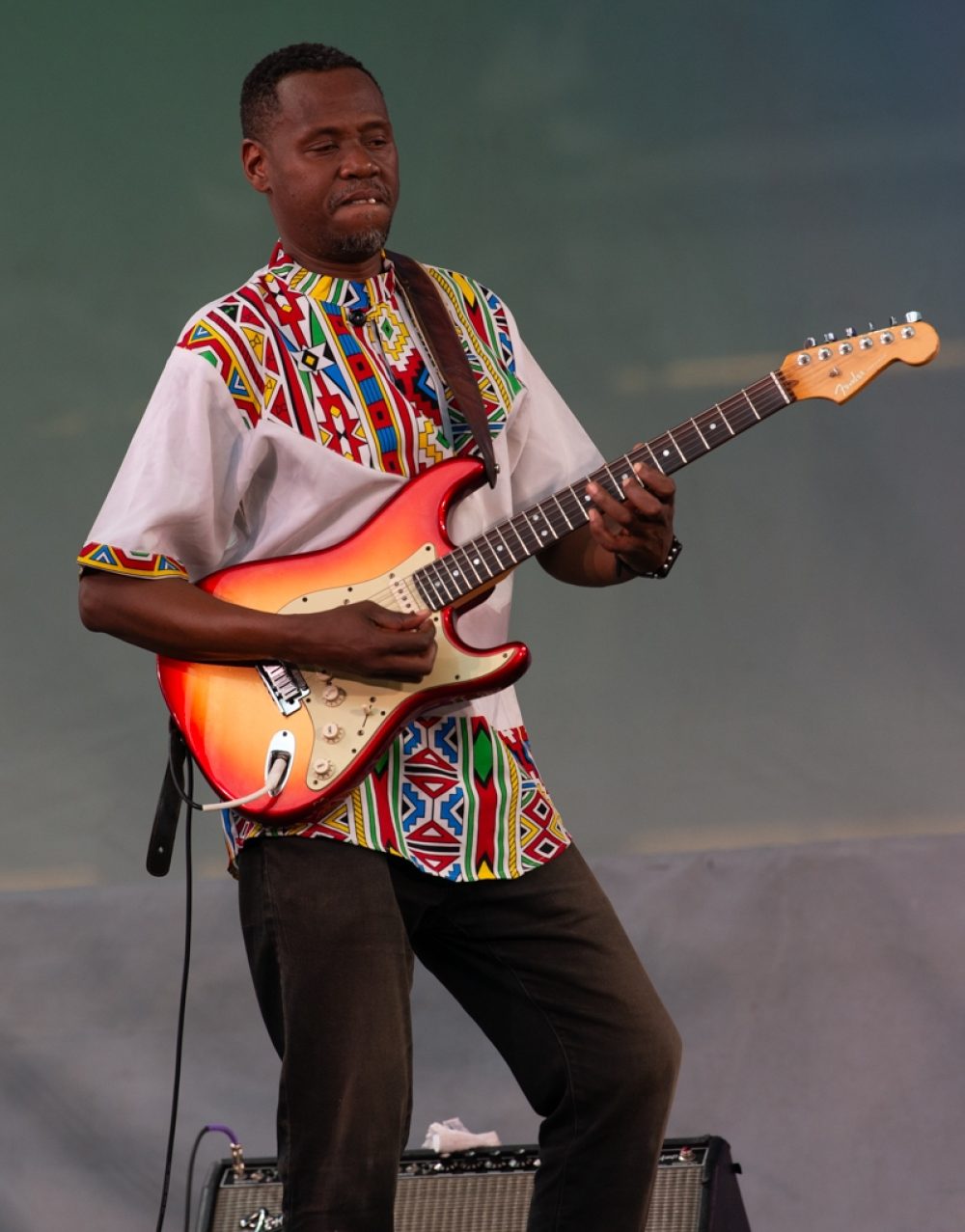

With that song I used as the bedrock traditional drumming. You can hear in the background that it just keeps going. It's kind of relentless and it's the driving force. Then we put a bass line on top, and it was great just the drums and the bass on their own. But I have this really incredible guitarist, Sunnyboy Mthimunye. He’s one of the last young people playing traditional guitar. So we added Sunnyboy quite late in the process because we had kind of a few iterations of the song. This one and one other might be the only ones that have electronic drums on them and, you know, it feels different.

It's really strong. I love that song.

Thank you very much. So, yeah, we then added this friend of ours who is a hip-hop producer. He put down 808 drums and things like that. And once we brought the guitarist and the percussionist in, we decided to rerecord the whole thing with everybody again. And when we did that, we were kind of jamming until it led to that f B section at the end.

A lot of the songs took quite a while to make. I kept coming back to them and figuring out what else to put in there. For instance, all the talking voices on the album, those were added almost a month before I was due to finish the mixing. I was sitting there thinking something was missing. Voices, yeah. And so I added Steve Biko’s voice and others.

Let's talk about “Kunzima,” the one that starts with the mouthbow and has the two very different sections going back and forth.

That song was produced by Meshell Ndegeocello and I think you can really hear her. She has a luxurious feeling that she brings to the music. Really cinematic. I didn't want to have the songs be a verse and a chorus and a verse and a chorus and a bridge and then a chorus. Michelle was really instrumental. In the songs that she produced, I really loved how she interpreted these B sections.

How about the “With Love to Makeba.” I read in the notes that this is a reinterpretation of one of her songs.

Yes, it's a song that she recorded in an album that she did called The Guinea Years. This is a fascinating period, and that has always been my favorite Makeba album. And so the song is called “Moulouyame” on that album. Miriam Makeba has one of those voices that always nudges at you. I think for every African vocalist, she sits as this kind of center on which we all pivot. Maybe in her time, she would have had someone else. But since her presence every African vocalist really cannot resist calling back to her. When I was 19 years old, my second radio hit was a tribute to Miriam Makeba, and it was a remake of “Pata Pata” that we did.

That was with Bongo Maffin. I remember.

Yeah, in the mid-90s. And I did another tribute to her on my previous album called Belede. So this would be the third time that I overtly paid tribute to her on an album. And I love this song because I was able to not only pay tribute to her, but pay tribute to the people of Guinea for keeping Miriam and protecting her for us when she had no home.

I hear a kind of tension in your version between the muted guitar line and the piano parts, which are really reharmonizing the song. It's almost discordant. There's a real darkness in this interpretation.

Yes, it does feel like that, right? I don't know how intentional that was because I never went to school to make music. I just kind of make what feels comfortable to me at the time. And I think it was a kind of melancholy in the room that day. There was a darkness that crept into it. Even in the mix, we first had the guitar quite high up and the piano beneath that, and I wasn't satisfied. So I brought the guitar way down so that it's kind of in the background, because the guitar line is the thing that takes us back to the original song. It’s there only as a suggestion of the original.

Let’s talk about “Fela Khona,” which has these interesting choral interventions. And the words are “Don't save me. Don't rescue me. I want to die right where I am.”

This is someone who’s very much in love. Or at least obsessed. You're in a place you don't want to leave. You don't want it to end.

And one more. “Xandibona Wena.” Again, this one has that strong four-on-the-floor beat that always makes me think of Zulu music. But at the same time, it's rather ethereal with choral backing.

And Thandi Ntuli’s really exceptional piano playing kind of creeps in every now and then. I like to clash these worlds together. Percussion is something that I think a piano player would not consider at first. And so when Thandi came into the studio, she was sitting on her piano and just holding the keys like this, listening to how the percussion was going. She was like, “Okay, okay, okay, okay.” So I like this idea of us finding new ways, new sonic languages, new sonic roots. I produced this song and “Emini,” which are the two you pulled out. Maybe they're fascinating because they come from someone who really doesn't know the rules.

You're making your own rules.

I’m making my own rules. I love this idea of working from a place of not knowing. It makes me feel like I'm creating like a child, with this naivety, without knowing that you can't have that with that, you know? And sometimes when we play the songs live, and things start to become interesting, because now that creates a discord and we have to really figure these things out. But when I'm in studio, it's only about whether it sounds correct to me to my ear.

Well, the lyrics for this song go well with that. “The heart wants what it wants.”

It doesn't care what the rules are.

Well, thanks Thandiswa. It’s a pleasure to speak with you again.

Thank you.

Related Audio Programs