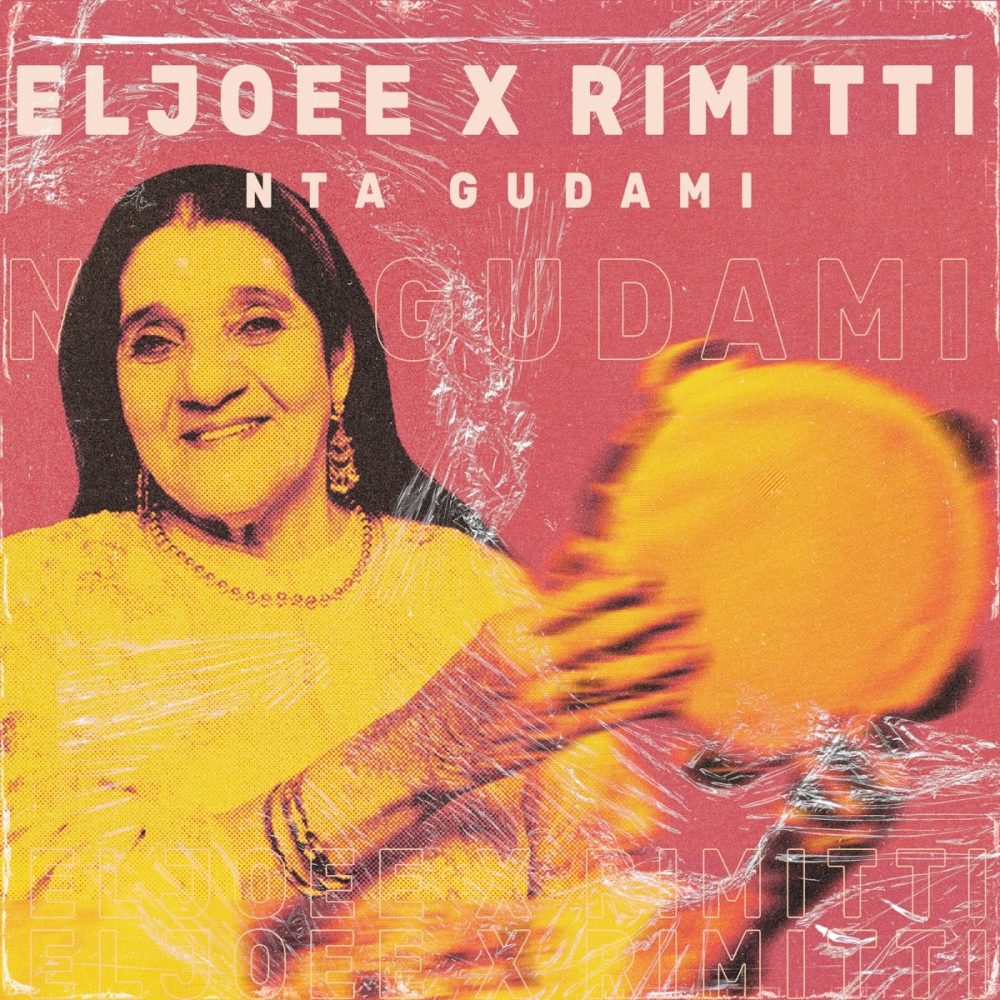

In the tense summer of 1962, in a dimly lit bar on the outskirts of Oran, Algeria, revolution wore an unexpected face. Cheikha Rimitti stepped onto the stage, her shoulder deliberately bared in the style that had earned singers like her the scandalous title "women of the cold shoulder." The conservative audience shifted uneasily – not just because of her presence, but because of what that presence represented. In French colonial Algeria, where women were forbidden from public performance, the very existence of the cheikhas was an act of defiance.

These female performers had emerged from necessity in the 1920s, when economic collapse forced orphaned and lower-class women to survive by adapting the traditional male cheikh style of singing. They performed in bars and brothels, often veiled, their faces forbidden from record covers, their very existence a challenge to colonial and patriarchal power. Their songs spoke of what proper society wouldn't: poverty, desire, prison, the bitter taste of colonial rule. This new style, called raï, was dismissed as a degraded form of traditional malhun music. But in its raw honesty, it captured truths that could be expressed no other way.

Her voice – defiant, rooted in ancient rhythms yet speaking to modern struggles – carried lyrics that made the audience lean forward despite themselves. Within months, the newly independent Algerian government would ban her from radio, forcing her underground. But like the traditional rhythms she transformed, Rimitti proved impossible to suppress.

Across the continent in Lagos that same year, 1962, a young drummer named Tony Allen was discovering his own musical revelation. Combining traditional Yoruba rhythms with the sophisticated patterns of American jazz, he developed a technique that made his four limbs sound like an entire percussion section. His hi-hat might dance like Max Roach while his feet laid down patterns from ancient street ceremonies, creating what fellow drummer Ginger Baker would later call "the most complicated drumming I've ever heard."

These weren't isolated innovations. Across Africa in the 1960s, as new nations emerged from colonialism, musicians faced a crucial challenge: How could they create something authentically modern while honoring their rich cultural heritage? Their answers would not only transform African music but reshape global pop culture itself.

The revolution began with rhythm. In Nigeria, when Allen joined forces with Fela Kuti, they didn't simply combine traditional patterns with modern instruments – they reconstructed the relationship between rhythm and meaning itself. Traditional Yoruba drumming had always been a language, with specific patterns carrying specific messages. Allen and Fela maintained this principle while creating entirely new vocabularies. A typical Afrobeat song might layer militant marching patterns beneath flowing jazz-inspired cymbal work, while traditional talking drums engaged in dialogue with electric guitars. The result was music that spoke simultaneously to the past and future.

One of the earliest complete performances capturing the full power of the Afrobeat revolution, with Tony Allen's innovative drumming driving the band.

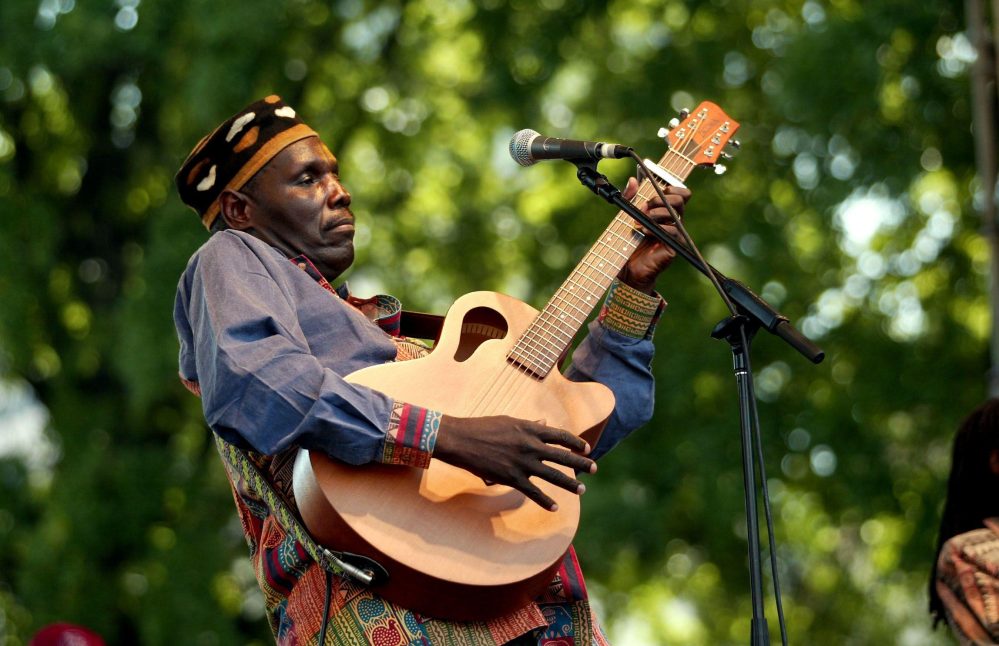

This transformation of tradition took different forms across the continent. In Zimbabwe, Oliver "Tuku" Mtukudzi developed a sound that wove together the mbira patterns of Shona spiritual music with the driving rhythms of South African mbaqanga. But his real innovation was in how he approached traditional wisdom. Over 66 albums – one for each year of his life – he adapted the Shona tradition of using proverbs to teach moral lessons, crafting lyrics that worked on multiple levels. A love song might also be a critique of political corruption; a dance track could carry messages about social responsibility.

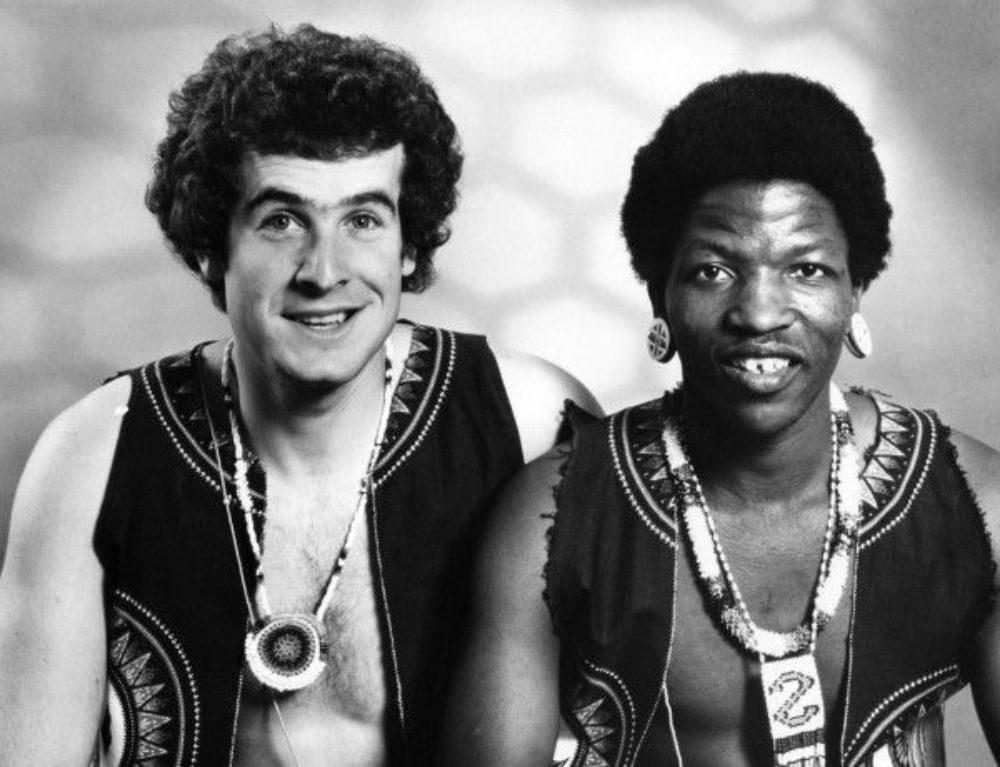

The act of transformation could itself become a form of resistance. In apartheid-era South Africa, Johnny Clegg ventured into the technically forbidden spaces of migrant workers' hostels to learn traditional Zulu music and dance. His bands Juluka and Savuka didn't just mix musical styles – they proved that culture could transcend the artificial barriers of race. Every performance became a demonstration of what South Africa could be, with traditional Zulu kick-dancing seamlessly blending with Celtic folk melodies and mbaqanga grooves.

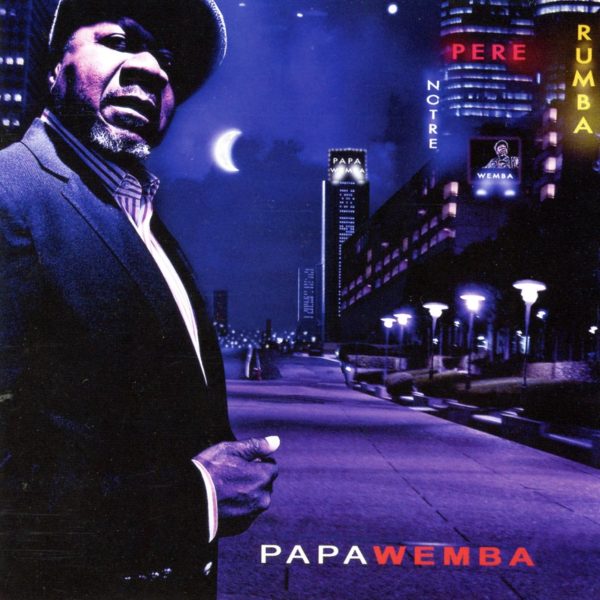

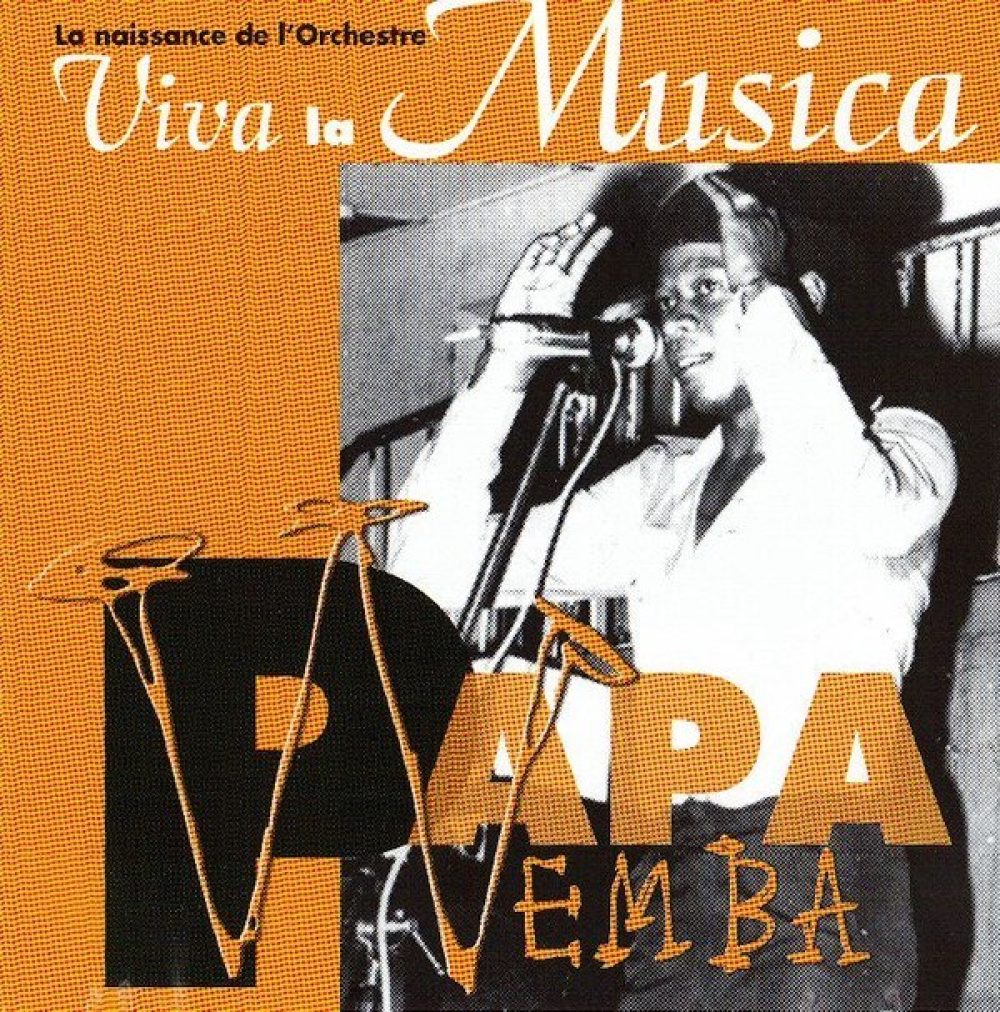

In Congo, Papa Wemba took the sophisticated sounds of rumba – itself a product of African rhythms transformed by their journey to Cuba and back – and injected them with urban energy and rock attitude. His band Viva la Musica maintained the intricate guitar patterns of traditional Congolese music while adding new layers of electronic instruments and modern production. His influence spread beyond music into fashion and cultural trends, proving that tradition could be both preserved and reinvented.

This spirit of transformation continues to ripple outward in unexpected ways. Listen to Burna Boy, one of Africa's biggest current stars, and you'll hear echoes of Fela's political consciousness wrapped in production that wouldn't sound out of place in an Atlanta trap studio. The South African genre Amapiano takes traditional rhythms and rebuilds them with electronic elements, creating something both ancient and futuristic. Even European electronic producers like Four Tet now regularly incorporate African polyrhythms into their work, proving how these innovations continue to shape global music.

But perhaps the most profound lesson from these pioneers was philosophical: They proved that tradition isn't a fixed point in the past but a living force that gains power through transformation. When Rimitti's music was banned from radio, it spread through private parties and bootleg tapes, adapting to new technologies while maintaining its essential truth. When Mtukudzi needed to critique Zimbabwe's political situation, he drew on centuries-old techniques of coding messages in seemingly simple songs.

"People think we were breaking with the past," Tony Allen reflected near the end of his life, "but really, we were diving deeper into it, finding new ways to make it speak to the present." He was right. These six musicians didn't just create new sounds – they revealed how tradition, when approached with both reverence and imagination, becomes not a constraint but a catalyst for revolution. In doing so, they didn't just change music – they demonstrated how culture itself could be simultaneously preserved and transformed, a lesson that resonates far beyond any single song.