Hailu Mergia was one of the leaders of a revolution in Ethiopian music in the 1960s and '70s. There was a moment which began with the failed coup against Emperor Haile Selassie in 1960 and ended with the successful coup by the totalitarian Derg government in 1974, when Addis Ababa was swinging to the beat of freedom and modernization along with the rest of the Western world.

Born in a small town in the Showa Province, his family moved to Addis when Mergia was 10 years old. He worked various jobs, but also began learning to play the accordion., He started performing professionally as a teenager. Soon, though, the organ (and later, synthesizers) became available and he switched to that. He and his group, later named the Walias Band, held court at various nightclubs. Eventually, they won the coveted position of house band at the Hilton Intercontinental Hotel in Addis, playing their innovative blend of jazz, soul, funk and traditional Ethiopian music, known often as Ethio-jazz. He continued to perform at the hotel, even under the Derg regime, for close to a decade.

“In the '60s,” Mergia told us before his trio performed at the 2019 Festival International de Jazz in Montreal, “I used to play different nightclubs, local nightclubs, as a freelance. Then I started playing at the Zula Club. That's where we formed the band."

“They used to call us the Zula Band,” he continues, “because we were at the Zula Club, you see. Up to then, everyone was hired by the owner individually. We didn't even own our own instruments. For example, they had an accordion there that I would just play when I was there. But this was all a very new kind of idea to have a band. The owner of the Zula Club had been a musician and singer, and I told him that I would only do it if we could form a band, and he loved the idea. But when we used to first play in the beginning at the clubs, it was always as freelancers. And we would get paid each night. Some would get paid, say, six dollars and others would get eight dollars – if the owner liked you, maybe he'd pay you more money.”

In those days, there was a tradition to collect two dollars a night from each musician that would be put aside, and after 15 days, they would have a lottery and whomever won got a bonus.

“We call it in Ethiopia ekud,” Mergia explains, “which is a tradition in villages for a long time, they might even raise like a million dollars. So finally we decided why don't we use that money to buy our own instruments, because if, say, we get kicked out of the club we won't be without instruments. We wouldn't have nothing. So that's how we started it. We were now getting paid all together as a band and split the money, but again kept the two dollars per person for the lottery.”

The band left the Zula Club for Venus Club. “But now we are growing and we need another name other than the club name,” he says. “One of our friends, an artist, named us the Walias Band, which is a bird only found in northern part of Ethiopia.”

At that time, there were many opportunities to hear Western music, and Mergia was particularly drawn to American jazz and soul organ players, especially Jimmy Smith and Booker T. Jones, of Booker T. and the MG's.

“I was listening to a lot of Jimmy Smith albums. He was very popular in Addis then. And Booker T., as well. But Jimmy Smith was very well known in the country. There was one club I used to go to and they would play his version of 'Chain of Fools'. It would drive us crazy. Me and the sax and the guitar player of the Walias Band, we would listen to that 45 until we wore it down, so we decided we had to learn how to play it then at the club. I met Jimmy Smith in, I think, 1984, in a jazz/blues club in Georgetown. I told him the story about how much he meant to me back them. I gave him a copy of my CD which was a first time for me. I'd go see lots of jazz music in Los Angeles, New York, Washington D.C., but I just would sit and watch, you know? But I gave Smith a copy of the CD and he called me on the phone and said, 'I love this music. I don't know what it is, but your songs are cool.'”

We asked Mergia if he could take us back in time to what it was like to play in the Hilton during that golden era.

“Well, first we'd play dinner music from 7 o'clock to 10,” he recalls. “We would play standard tunes, like 'Strangers in the Night,' 'Misty,' or all these very popular songs. Sometimes we'd also play Japanese music or Indian music. We played all different international music. Most of the times, we could buy the reel-to-reels of the songs and learn from that. Sometimes we'd get sheet music. But also because we had international customers, they would come and request we'd play some Japanese or Indian song, or give us a name. If we didn't know it, we'd tell them we'd find it. Whatever it was. There was no Internet back then. We'd collect the titles, go the music store and if we didn't find it there, we'd go find someone who had a big record collection. We had a lot of friends like that. And sometimes, the customer would bring us the music. And that's how we studied it. We wouldn't bring any Ethiopian rhythms to it, just play it how it was. We would copy the arrangements, but maybe during the improvisation we'd bring our own kind of style to it.

“Then at 10 o'clock, dinner time was over, and around 10:30 or 11 p.m., the dancing program would start. Then we'd play any kind of funk or blues, everything. The dinner crowd would leave. The tourists would leave early and another crowd would come. This is around the late 1960s. Dance music was very good back then.”

“So, at first we’d just play the songs as they were,” he continues, “but having those late night dance parties, we were able to start improvising, and we would introduce Ethiopian melodies into the improvisation. We were then able to change Ethiopian music into a more modern style, at the same time. We would add a little of this and other styles and that's how we were changing it. And that's how the work was done. So, I would take these popular Ethiopian melodies, change the rhythms, and then people would be surprised because they knew that kind of melody but with different kind of rhythm. It was something modern, but they were very old songs. And so it was not just that they were hearing Western music, but it was their music they were hearing. “But then, after the revolution, we played less. They asked us at the hotel if we could stay and play until 5 o'clock in the morning because of the curfew. People couldn't go nowhere, so let them stay until morning. This was only Saturday nights for the all-nighters. It was really hard. We had to drink a lot of beer to keep going. The Hilton, you see, was an international hotel, there were other local hotels for locals. We were playing six days a week. It was a good experience because when you play this kind of music you learn a lot. Also, you never knew who was going to walk into the hotel – actors, musicians, diplomats, big shot people. Richard Roundtree was there filming Shaft in Africa. Other actors, like Robert Wagner and Stephanie Powers came to see us. We played for almost all the African presidents who came for the anniversary of the African Union. Duke Ellington was invited by the state and we opened up for his band at the Hilton. I didn't get to talk to him, but after their show almost all his band members came to see us and played with us that night.”

However, when daybreak came, the realities of living under the Marxist Derg government were inescapable.

“They wouldn't allow any radio stations to play Western music,” he continues. “That door was closed. But, you see, people got very tired of listening to the revolutionary songs very quickly. So I went to the television station and talked to the manager and told him why don't you give me two programs, 45 minutes each, and we would only play our music. And he said, 'O.K., let's do it.' And people started calling and saying they wanted to hear more, and the government, because they wanted to keep the people happy, they let it happen. But the sad thing is that because there were so few resources, the station would copy over the video for whatever official government program, so there are very few recordings from that time.

“The new government had also destroyed all the records in the record stores, and they arrested some musicians who had political ties. We were not worried so much about all that because we were playing at the Hilton hotel. For one thing, it was not nationalized. It was still run by the Hilton operation. The government had no real control over it. And also we were getting paid by the Hilton. Yes, we would have to play free shows when the government would tell us to. If there was some kind of festival and they told us to play, we would have to. You didn't ask questions, you only asked: 'What time do we have to come?'”

In 1981, Mergia and the Walias Band were invited to America for a tour organized by Amha Eshete, the former owner of famous Harambee Music Store in Addis Ababa and later founder of Amha Records, which was the first and foremost label to record Ethio-jazz back in the day. Eshete had already fled Ethiopia and settled in Washington, D.C., where he ran both an Ethiopian restaurant and nightclub. While the tour of the United States did not bring the acclaim to this style of music they all had hoped, several of the musicians decided not to return home and stayed in D.C. What happened next to Mergia is the stuff of legend: His 20-year odyssey from struggling immigrant cab driver to being rediscovering has been recounted many times, in publications including the Washington Post and The New York Times. It's also been retold many times on both radio and television.

If you are unfamiliar with the tale, rather than us spending time doing so here, here is a short documentary, one of the many versions you can find online, that does a good job of it, as well as offering a visit with Mergia in his home and his taxi, just as he was regaining attention by the world.

Hailu Mergia Takes Off – Far Off Sounds

Meanwhile, French musicologist Francis Falceto discovered Ethio-jazz about the same time as Mergia arrived in the United States. Eventually, partnering with Eshete, the two managed to retrieve most of the original masters (and later those recorded by Philip-Ethiopia and Kaifa Records), and began releasing the Ethiopiques series in 1998. To date, there are 30 volumes of Ethiopiques, which has introduced the world to this music which might otherwise have been completely forgotten. (For an excellent retelling of this story, check out the documentary: Ethiopiques: Revolt of the Soul, available to rent on Vimeo.

“What Francis and Amha were doing,” Mergia says, “was a good thing, because our music started to become internationally known. Remember, when that music died in Ethiopia, it was dead. It went nowhere. When the Ethiopiques came out, I give Francis and Amha credit because it was alive again. But we don't get any money from it.”

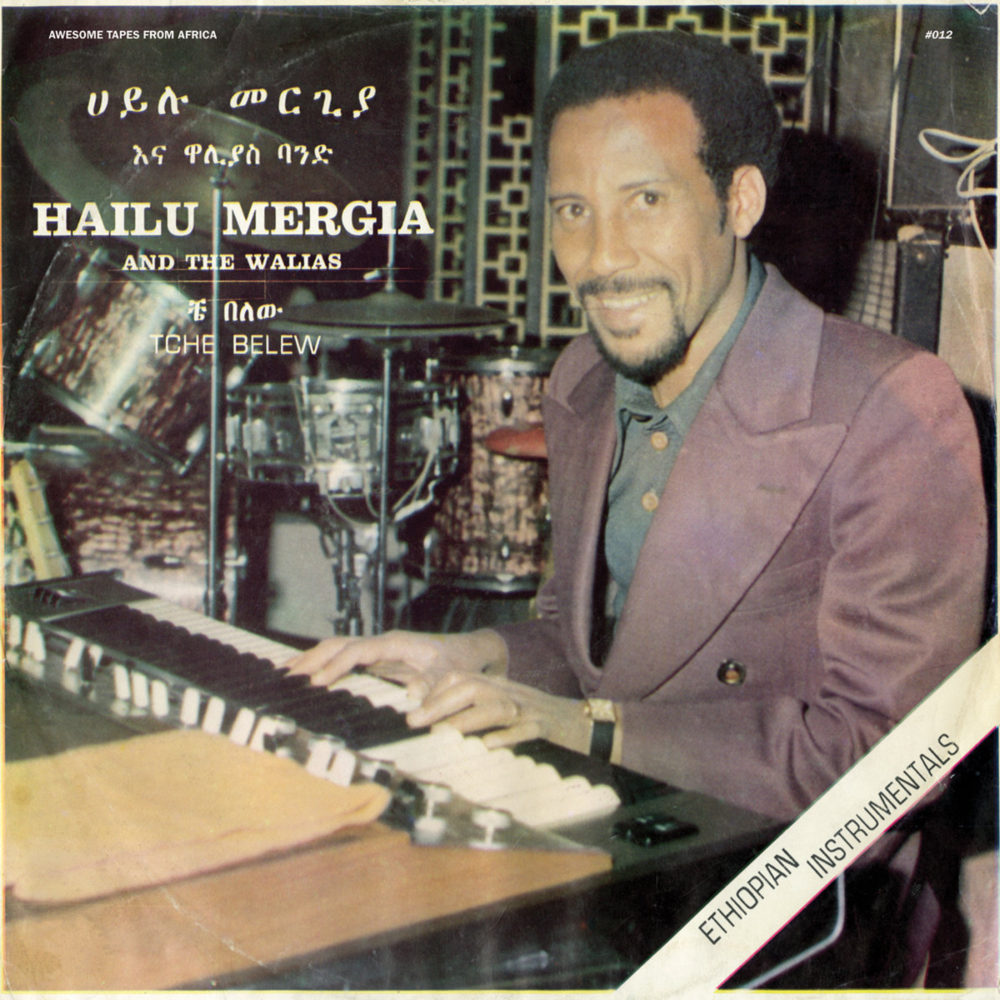

The first artist who had his career rebooted was Mulatu Astatke. But it wasn't until Brian Shimkovitz discovered Mergia's 1985 cassette Hailu Mergia and His Classical Instrument (the “classical instrument” refers to the accordion), and re-released it on his own label, Awesome Tapes from Africa, in 2013, that Mergia began to find a new audience and being invited to perform again, eventually quitting driving a cab and playing music full time in 2018.

One of his Walias Band's song which has been covered many times over the last decade is “Muziqawi Silt.” We asked Mergia about the song and its new-found popularity.

“I didn't write 'Muziqawi Silt,' Girma [Beyene] wrote it. We needed some original songs, so I asked him to write one. The funny part is that when I asked him, 'What is the title of the song?' He said he didn't know and told me to come up with something. So it means, something like 'the blend of music' or 'the art of music.' Girma is a very talented person. He can do any kind of stuff. But he is a very quiet, very cool guy. He was working for a long time at a gas station in Washington D.C. The first time I heard a cover of 'Musicawi Silt,' I was so happy. Even Yo Yo Ma plays it.”

“It's so incredible,” he smiles. “That makes me so happy to have something from your album become so popular around the world.”

In 2018, Mergia released a new album, Lala Belu, his first collection of newly recorded music in over two decades, with both original and traditional songs. Now in his 70s, he continues touring with his trio. As he performed that night at the L'Astral Club in the heart of the Montreal Jazz Festival, his joy of being back on stage was felt by everyone there.

Related Articles