Let me say it from the outset: Michael Baird is a madman, one of these people so profoundly obsessed with a musical mission that it has more or less consumed his life for 30-plus years. Some might say the same about me, but Baird’s laser focus on Zambia, his childhood home, and his dedication to recording otherwise impossible-to-find music, in the field, puts him in a special category. My hat goes off to him for producing his most ambitious project to date: eight albums of his Zambian recordings packaged in two elegant booklets—four CDs per volume—with extensive notes about each track and a fine collection of photographs to boot.

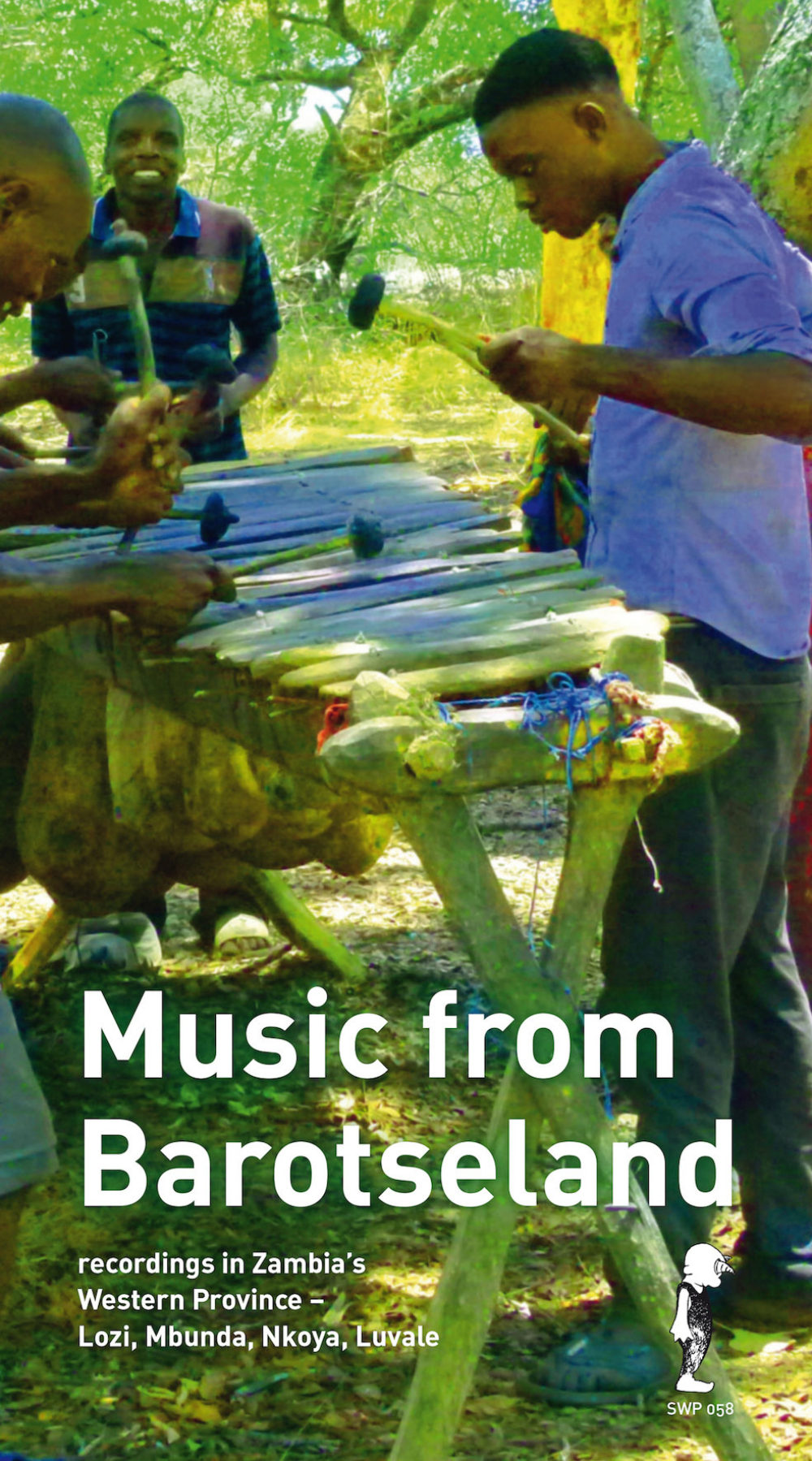

The two volumes are Luangwa to Livingstone: Music from Zambia – Chikunda, Nsenga, Soli, Cewa, Tonga, Ila, Leya and Music from Barotseland: Recordings in Zambia’s Western Province – Lozi, Mbunda, Nkoya, Luvale. These albums offer a dazzling array of southern African drumming, choral singing, rootsy guitar and xylophone traditions, and disappearing lamellophone styles played mostly by ancient—in some cases, deceased—virtuosos. There is also a DJ-friendly vinyl release, Zam Groove, highlighting seven particularly rocking tracks. You won’t find this music on Spotify, Apple Music or iTunes: Baird has sworn off streaming services on principle. But all the music can be purchased via www.swp-records.com and via https://swp-records.bandcamp.com for digital downloads. Moreover SWP Records are distributed in North America by Forced Exposure, and these titles are available in physical copies—recommended—on Amazon.

Before delving into this cornucopia of music, a word about Baird, who, by the way, has also released over 20 volumes of Hugh Tracey’s legendary field recordings on his SWP Records label, and who was also a key contributor to Afropop’s Hip Deep program, "Hugh Tracey: Discover and Record."

Baird was born to British parents in Zambia (then Northern Rhodesia) in 1954. His father, a sociologist, and mother, a nurse, were looking for “an opportunity to escape a cold, tired, hungry post-war Britain,” as he put it in a recent Skype call. “I grew up with African music,” he said, “Literally. I heard African drumming already in the womb. Well, you would, wouldn’t you? It’s quite loud.”

Repatriated to England at age 10, he discovered the Stones, Beatles and Kinks. Classical music was all but incomprehensible, particularly for the silent decorum of the audience. Then Baird saw the Jimi Hendrix Experience live on television. “That was like recognition for me,” he recalled. “They really went for it. They were sweating, exorcising, trying to break through. That was something I found very African.” As a boy in Zambia, Baird was surrounded by music, but he was more interested in insects and animals. It was only later, in England, that he discovered an irresistible compulsion to become a drummer himself, which, of course, he did…

Zambia has a different cultural legacy than neighboring Zimbabwe. (They were Northern and Southern Rhodesia during the colonial era.) British Rhodesians found the Zimbabwe plateau a delightful habitat, free of tsetse flies and contagions. Northern Rhodesia was less attractive, hot, humid lowlands, but also a source of copper in the north. The colonizers were focused on extracting resources, but not on building a new homeland. That meant there was less incentive to interfere with and stigmatize local culture, and as a result, many traditions have survived in Zambia and are proudly practiced today. Just the same, Baird notes that “music is disappearing at an alarmingly fast rate.” The post-colonial hangover has resulted in generations of Zambians who are more interested in embracing western culture than in maintaining tradition, and the arrival of the internet has only accelerated that trend.

After visiting the Tracey archive in 1996, Baird continued up to Zambia and Zimbabwe on his first recording trip, inspired by Tracey’s lifework. But most of the recordings in these new volumes come from two expeditions in 2016 and 2018. If you look at a map of where he recorded for these two volumes, you will note that all the work was done in the southern half of the country, in five of its 10 provinces. This was mostly a matter of where he found opportunities to travel with friendly helpers and affordable transport.

“I am not an ethnomusicologist,” says Baird. But his notes do provide meticulous detail about artists, ethnic groups, localities, performance techniques and song lyrics—the sort of stuff that deepens the listening experience. “I take the music seriously,” he says. “I go out to record as a musician above all else, I am recording my fellow musicians, which is how I get such good results. I don’t act like some hotshot producer, telling musicians where to stand and how to play, I build up a rapport and pay everyone handsomely.”

And the result speaks for itself.

The listening journey begins with the Chikunda people, military slaves on the mid-19th century Portuguese prazos (estates) of Mozambique. They went on to create their own society, not unlike the Maroons of the Caribbean. Chikunda music features fast, at times frantic, rhythms, played not only on drums but on cooking pots and plastic jugs. A track of rocketing ngororombe music—performed by a cadre of one-note pan pipes—is a standout. The first album also includes Soli choral polyphony with distinctively beautiful harmonies. The Cewa kalimba and guitar pieces that conclude the volume work around clave-like timelines and three-chord harmonic progressions that suggest an affinity with Congolese music to the north.

Volume two concentrates on a single Tonga ensemble, the Kalonda Band, originally featured on an earlier SWP release, Zambia Roadside. The music is tuneful, lively, guitar-based skiffle, often in 12/8, and thoroughly delightful, and on this album, we get the complete set of Baird’s recordings made in 1996 and 2002.

Volume three, Southern Province Mix, is a potpourri of bow and lamellophone tracks, women’s initiation songs, funeral and healing songs, and recreational numbers, including a standout by the band Green Mamba. Chris Haambwiila, an Ila master of numerous instruments, shines especially on the bow called kalumbu.

The percussion pieces on this album, and elsewhere, are interesting. Baird notes that in West African drumming, the highest pitched drum is generally the soloist. In these Zambian traditions, it’s often the opposite, with the lowest pitched drum taking the lead. There’s a rolling, melodic quality to these southern African drums.

A women’s initiation song performed by Tonga women marks a joyous end to a month of seclusion. The rhythm is thick, a tumble of 12/8 time, with beats falling like heavy rain drops pierced by ululations as the singers invite young men to come and compete for the initiate. I pointed out to Baird that some of the vocal harmonies, full of triadic harmony that follows familiar diatonic chord progressions, sounds like it carries an influence of Western church music. Baird said that is possible in the case of a pop skiffle band like Green Mamba, whose “In the Banana Plantation” on this volume has a distinct Congolese flavor. But for the traditional groups, he says, “To my mind the answer is no. There is no influence of Christian singing at all. It’s traditional harmonizing.”

A number of songs on these albums take aim at “witchcraft.” “Witches have pissed me off,” sings Short Mazabuka. Baird concurs that conmen witchdoctors are “a scourge…rule by fear,” but he is careful to distinguish witchcraft from traditional healing. That distinction is not shared by all these singers. “Don’t get tricked into taking traditional medicine,” sing the Chiyema Traditional Singers on volume four, Leya Ceremony and Songs.

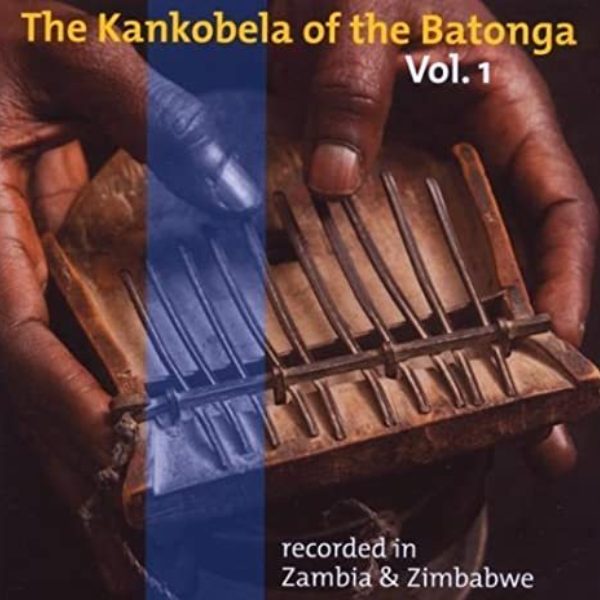

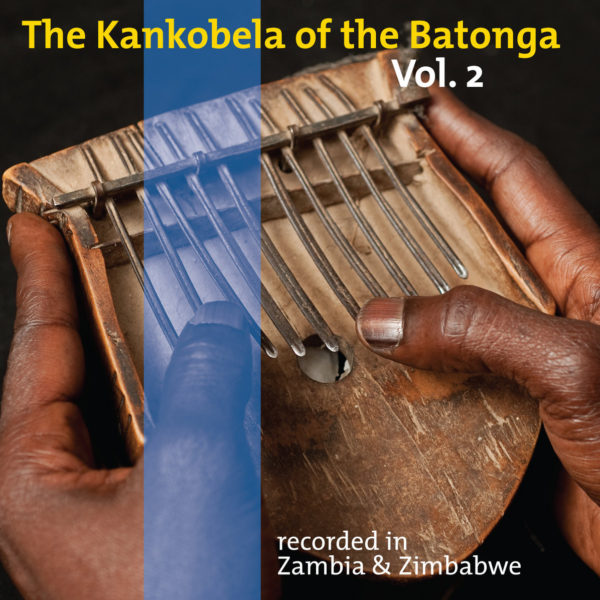

This Southern Province Mix album ends with a remarkable lamellophone piece played on the nine-note kankobela by Aaron Nchenje, born in 1933. His instrument—older than he is—produces wonderful buzzes and rattles and his rhythms are elusive and squirrelly. Fans of mbira music from Zimbabwe or ilimba music from Tanzania may be surprised to learn that these Zambian lamellophone traditions have no connection to ancestor veneration or spirit possession ceremonies. “In Zambia the lamellophones have nothing to do with calling the spirits,” says Baird. “It’s just for passing the time, social commentary, entertainment. Same in Malawi and Congo.” The fact that these traditions are disappearing has nothing to do with religious stigma. The lamellophone just got replaced by the guitar, as Baird puts it, “a symbol of modernity.”

The final CD in this collection begins with extended selections from a Leya girls’ initiation ceremony recorded in 1996. The Leya are an offshoot from the Luba people in the Congo; they came south into what is now Zambia in the 1600s. With a choir of over 60 singers, three ngoma drums interacting alongside a deep-toned namalwa friction drum and chattering silimba xylophone, all going at once, this is not an easy sound to capture. Taking a page from Hugh Tracey, Baird moves through the scene with his microphone, highlighting various elements of this sumptuous sonic tableau.

The four albums in this volume from Zambia’s Western Province bring a new set of surprises: friction sticks, pod drums, friction drums, more lamellophones and xylophones and a whole album of Barotse guitar, a young genre based on the rhythms and vocal style of much older kangombio (lamellophone) tradition.

Barotseland is remote and difficult to access. There was just one poorly maintained road from Lusaka, until a second road coming up from Sesheke and Nambia was recently built. Baird says this is no accident. Like the Tuareg in Mali or the people of Casamance in Senegal, the inhabitants of Barotseland never signed on to being part of Zambia. “Barotseland got incorporated quite deviously,” says Baird. “The British did their thing, with a nice cup of tea. They gave the king the suit of an admiral with all the feathers on top of his helmet and allowed him to visit Britain. So they sort of bought him, and he got tricked. His Barotseland Kingdom got incorporated into what then became the colony of Northern Rhodesia. But their music and own language are part of their identity, and they’re very proud of it.”

We start out with Siyemboka, the national Barotseland style, involving a silimba xylophone and three or four drums. This is exuberant recreational music, once again linked with girls’ initiation ceremonies. That silimba, by the way, can be five meters long, with up to 30 notes and played by four or five people at once. These are wild, rowdy tracks, full of buzzing drum tones, whistles and ululations. One track by Mumbumbu Cultural Group hits on a common theme in these songs: being under-appreciated. The singer’s response: “I will go wild like a wounded buffalo.”

Other songs comment on social issues like infidelity and polygamy (criticized here). And again, there are a number of anti-witchcraft songs. Baird points out that these practitioners are feared, and that it takes some courage to criticize them publicly. But he says, “In songs, you sing the unspeakable. Music makes you untouchable. ‘It’s not my opinion; it’s just the song.’ You can deny it.” Like griots and court jesters, these entertainers enjoy special license to speak their minds.

The second album in this set is catnip for this African guitar lover. Barotse guitar music is an example of a traditional style that has jumped instruments from the kangombio lamellophone to the guitar. This is minstrel music, informal and fun. There can be glass bottle or metallic percussion, but the defining features are the solo guitar, replacing the kangombio, and vocal arranging that involves one male voice in normal register, and another singing in falsetto above. We get three different bands on this album—all delightful—and one wildcard track by a gentleman playing a homemade five-string banjo.

Kangombio Silimba Jazz, the penultimate album, is arguably the most riveting of all. The opening silimba numbers by Pelekelo Mufalo on 15-note xylophone are not technically “jazz,” but they are free, intense and full of wonderful improvisation—close enough! Playing solo on the opening track “Kuwabile,” his hands seem to be everywhere, and the stereo imaging on the recording lets you clearly hear what each hand is doing. The piece was originally written for a Barotse king as he moves locations for the rainy season. But this song, like others here, is now performed in church, though perhaps not church as we know it. Baird notes, “Their African cosmology has been Christianized.”

The second half of this album brings the work of three elderly, disappearing kangombio players, including a cool, quirky instrumental piece. Apparently these players were puzzled by the idea of playing without singing, but one player did oblige Baird’s request. Alban Katete Kapemba hadn’t played his instrument since his wife died five years earlier, so it took him a day to get his chops back. But once he repaired the spider’s eggsack membrane to give his instrument its required buzz, he cranked out a few numbers, including two written to be performed at graveside.

The final album, Drums, Voices and Sticks, is what it sounds like, for the most part: a feast of percussion. Galloping grooves and polyrhythmic interplay abound. The pwita friction drum in a celebratory end-of-workday makishi song is a special treat. We also get praise songs, a hunting number and more initiation music. In a pause from the percussion, the Sibupiwa Cultural Group features 15 Nkoya singing richly harmonized songs of mourning accompanied by the sounds of dry grain on a tin plate, sticks struck together, and a metal bar on an iron bolt.

At the end of this journey, one may feel a little overwhelmed. It’s a huge variety of surprising sounds to come from a country little known for its music, even in Afropop circles. But as I spoke with Baird about the project, I couldn’t help but ask if he had designs on those remaining five provinces to the north. He seemed game. “The value of the music is great and there is so much still to be recorded,” he said. “If no one else is doing it, I somehow feel I have to do it…when I get the finances together.” Well here’s hoping he does. This is important work and as Baird notes, “There are too few of us doing it.”

Along with these releases, Baird is now completing a documentary film, Mutanuka and Syasiya, about the state of rural music in Zambia. Watch this space for more.