The first thing his bio notes is “You’ve probably seen him perform without realizing it.” And you probably have seen, or at least heard, Miroca Paris (pronounced in the Portuguese way, as “Parish”). For over a decade, he toured as percussionist with Cape Verdean diva Cesaria Evora's band. Now, he is stepping out on his own--with his own voice, his own music, and with his guitar.

Part of the Cape Verde musical Paris family--most notably his uncle, Tito Paris--Miroca's first memories are that of music. We had a chance to chat with him before his showcase that night at this year's Mundial Montreal. “My granddad was a banjo and bass player. He was the first guy who brought the electric bass to Cape Verde,” Miroca begins. “But he left before I was born. He was the first of the Paris's to go to Portugal. All the cousins, and now almost 80 percent of the family, are based in Lisbon--and each one plays with different artists.

“Cape Verde was hard back before 1975,” he continues. My granddad didn't have his own project. He would make music to make money to live. He did a little of everything. He would go to the sea as a fisherman at 4 a.m. until 11 a.m. Then he would come and have lunch, then he would sleep until 4 p.m. Then he would rehearse until 6 p.m., and then the party would start every night at like 10 p.m. Then he come home at like 2 a.m. just to drink a coffee, then go back to the sea at 4 a.m. He would sell the fish, take a nap--at our home, of course, then play. Sometimes he would go out at 2 a.m. to Santo Antão and transport people from one island to another, which was illegal to do then. Also our rum, called grogue in Creole, was contraband, so he would smuggle it and the people sometimes in the boats in the dark. No lights, just the boat. 'Go there! Someone will be waiting for you there!' And my granddad would sell the grogue, then go fish, then sleep, then play.”

And with the money he saved, Miroca explains, he built a house and filled it with musical instruments.

“Our house,” he recalls, “we would call it the train house--because it was small, but long like a train. And each room would have bands playing just like that. We didn't know what makes rehearsal rooms. We just knew that friends would come and play our instruments. This was in Mindelo. Me, my brothers and cousins, since we were little kids, would come over to the family house and grab an instrument and start playing. Even when I was one year old, I was touching the instruments. It was, and is, our life. I knew right away it was what I wanted to do. The first instrument I got was a guitar which I bought with my own money.”

As a small boy, Miroca would often go and watch his two uncles, Tito and Toy, perform, which inspired him to see being a musician was a possibility in his own life.

“They would be playing everywhere,” he says. “For me, Toy was really cool; but Tito was special. When he left, I missed him so much. Of course, he was an example for the whole family.”

Tito went to Lisbon at the age of 19 to play with Adriano Gonçalves, better known by his stage name, Bana, the king of the morna style of music from Cape Verde. But according, to Miroca, Bana had actually requested that Toy come to Lisbon, not Tito.

“They needed a drummer, you see,” Miroca says, “and Toy was a great drummer. But Tito was a bass player then. He started playing bass when he was even 8 years old. So when he arrived, they said 'Where is your drum?' He answered 'No, no, no. I'm a bass player.' And they were, 'Wait! You're not Toy?' He said, 'No, I'm Tito.'

“I think it was my grandmother,” he laughs. “You see, my grandmother, she was selling drinks and fish. And she said, 'Toy is already good, but I'm worried about my little one, Tito. He's not doing anything here and maybe the military service will call him to duty, and I don't want Tito to go.' So we all think that she did it. But because we all played all the instruments in the home, already on the first date, Tito was playing the drums. A year later, Toy went to play the drums and Tito moved to the bass. Manel, my uncle, was on the guitar. Then later, they all switched. Tito went to guitar, Manel went to bass, and Toy stayed on the drums.”

By the age of 15, Miroca was already performing with bands, as a guitarist and singer.

“When I was growing up in the '80s,” he says, “the music was really amazing. And the '90s too. The kind of music that was happening then for me was coladeira and funaná. The coladeira was the music of the north and funaná was the music from the south. Now it's more divided again, but before, when I was growing up, it was all mixed. So it was incredible back then to hear coladeira from the south with the North African rhythms and people playing a funaná in the north. How fun is that?

“It was that music that inspired me for my album. It's why I invited two of the greatest singers of that era who are singing on my album--Meno Pecha and Zeca Nha Reinalda. These are two of the greatest singers of funaná. Meno sings harmonies with me on the first song in the 'Funaná Medley' track, and Zeca Nha on the last. It was just so amazing.”

He also was listening to other music--from Brazil, the United States, but there was one African artist that was pervasive back then, he recalls.

“We would have a lot of TV shows with artists from Senegal and South Africa. Always, we'd see three hours per day of Youssou N'dour. Senegal is the country more near to Cape Verde,” he then adds with a chuckle, “I think it was like the only recording they had back in the time on the TV.”

We asked Miroca to speak a bit more about the various musical styles of Cape Verde.

“Before 1975,” he explains, “you see, funaná was a forbidden music. First of all, the Portuguese church, which had a connection to the government, would say it was a bizarre culture against the church because it had a spiritual element to it. And also in the politics, even worse, because music was our own weapon. You cannot, even if you're guarding a prisoner, you cannot forbid him to sing anything he wants. So we sing in Creole, because they could never understand what we would say. In the south, the Creole is even more difficult, because there was more Portuguese there. It was made to be hard for them to understand. Now in the north, we were also colonized by the English, which is why my Creole has so many English words in it.” He then smiles, “They also brought the cricket, and that's why we still play that.

“Now the coladeira,” he continues, “it's between morna and funaná. Morna is the main style that Cesaria used. If you play a morna, but add a little bit of tempo in it, it's becomes a coladeira. Cesaria was the queen of the morna and Bana was the king, and I had a chance of playing with both – the king and the queen.”

In 1998, about to turn 18, Miroca headed to Lisbon to join the rest of his relatives there.

“So many of my relatives, and my older brother, were already there,” he recalls. “There was this bar there, called B.Leza, it was basically the 'Paris bar,' because all the musicians were from the family. It was like a school for all of us.”

He tried to introduce himself as a guitarist/singer, but within families such as his, you have to fight for a place at the table--or in their case, the stage. So they told him to sit behind the others with some congas and pay his dues.

“So I had a little corner where I had my two congas,” he says. “Then three months later, I had a little bit of timbales. One month later, I had a bongo. I set it up not knowing what I was doing.”

Then one evening, Portuguese singer Sara Tavares dropped into the club and saw him in his little corner. Tavares is of Cape Verdean descent and made a name for herself initially as a pop star, winning a nationwide television contest, which led her to performing on the Eurovision Song Contest in 1994. At that moment in time, she was looking to change directions and go back to her roots.

“Sara was coming from a TV, more pop thing because she had these skills of getting high notes and very nice vocal skills and stuff,” Miroca says. “She had the support of all powerful record labels and TV people. But now she wanted to build something that was not so much TV. She told me once, 'I don't want to be a marionette anymore.' So she was on the streets of Lisbon searching for musicians.

“So Sara saw me with my strange set up and said, 'How you do that? Because you do it differently.' And I was like, 'I don't know. Am I doing something wrong?' And she said back, 'No, no. But you're doing something very crazy different. How is that possible? You will play with me.' So she took me from the bar just a year later.”

A year after that, legendary Cape Verdean record producer José Da Silva saw him with Tavares and hooked him up with Evora. However, whenever he was on break with Evora's band, he would continue to play with Tavares, which he has for the last 21 years. He toured with Evora for nearly 12 years until her death.

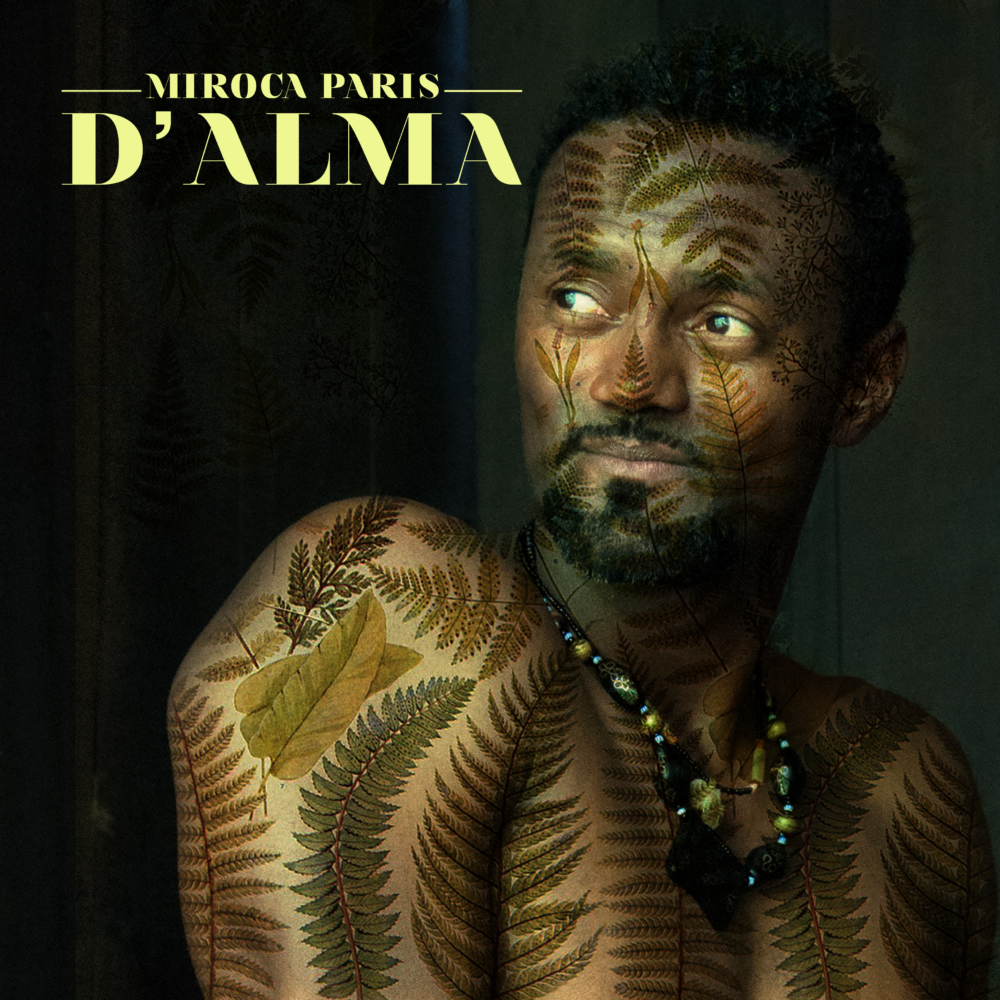

On cover notes to his album, D'Alma, released last year, Miroca gives a special thanks to both women. “[To] Sara Tavares,” he writes, “for showing me right directions and the great Cesaria Evora--wherever she may be--for her conviction of my potential, her continuous motivation for me to pursue my own career, for her wisdom.”

Asking him what he meant by “right directions,” Miroca explains that Tavares and Evora were like two sides of a coin: the former teaching him to focus on professionalism, and the latter, on spontaneity.

“Sara is really so professional,” he says, “so dedicated, focused. She would work us a lot, a lot of practice. Showing me how that's done. I wanted that because in Cape Verde we are different. We do music to entertain people, family and friends, not as a show. It's different. When I got to Lisbon, it was very hard to change everything, and Sara helped me to do that.

“So then I will talk about Cesaria,” he continues, “who was spontaneous and simplicity over and around. That's something also I didn't want to lose. Why? Not because of Cesaria, but because of Tito. Tito would do something very musical, but at the same time be spontaneous, still very Cape Verdean.

“Like on the first two albums of Tito's, it's very arranged, but at the same time he's still Cape Verdean. And I felt like I was losing a little of this spontaneity doing these charts and all this crazy stuff with Sara. But then I was able to work that all out after going with Cesaria. At first, I would show up and go, 'Hey guys! At 7 a.m. we do this, then 3 p.m. we do the rehearsal,' and they would be like, 'Woah, where are you coming from?' Then I realized, 'Ah, that it's Cape Verdean on stage.' Cesaria's first question to me was: 'Are you O.K.? Are you nervous?' And I explained that in Lisbon it's all very tight and professional. And Cesaria would say: 'No one is asking you to be here at any time. You're here with us. Everything is O.K.' So it took some time for me to come around – that we can be both professional but also just relax. It's about trying to keep the balance. It wasn't easy with the guys, but that was that.”

More on Miroca on his Facebook page.

Miroca also was doing session work with various musicians during his years with Evora, and says he wasn't thinking too much about what was to happen next for him. The way he sees it still, it's all a progression that has its own time signature.

“You start as a little musician,” he says. “This album is the result of a life that goes on natural. You start today, tomorrow you do something more. The next something more, and eventually it became this album. After the album, it becomes the shows. It goes. It's very natural.”

When he first started touring with Evora, he says, there was this one musician who would do her sound check before every show, as she didn't like to. But after a few years, this guy quit and Evora asked Miroca if he'd like to do it. He continued to do it for the next nine years until her death in 2011.

“So every day, for 30 minutes, I would do the sound check singing her songs,” he recalls, “and Cesaria would be off in the back stage. And then she'd say to me, 'Oh, I like the song you sing today. You should do you own thing.' And I wasn't even thinking about it. So it all became natural, and now I started to think about it. Because it was time. It was not forced. Though I could not do it at that time while with Cesaria. It was only after her death.

“Though I started putting the band together around 2009, but only because someone back in Cape Verde said, 'Oh Miroca, you sing, yeah? Well, it's my marriage, would you like to come sing some stuff?' And I was like, 'No, no, no!' 'But it's for me and my wife?' they'd say. So, O.K., I would agree to do the show. Then I'd be invited to play, say, the party for the municipality. It wasn't because I wanted to or that I planned it, it was because people were calling me. Then, it was all the big hotels and they wanted me to do their Christmas and New Year's shows. All this was happening when I'd go home to Cape Verde.”

When Evora passed away, he started thinking seriously about recording an album, but knowing he was no longer working with Evora, his phone started ringing off the hook to do studio work and tour with other groups, including Bitori, A.K.A. Victor Tavares, whom Miroca calls “the fount of funaná. He's 80 years old and still playing two-hour shows.”

Bitori – Cabalo (w/Miroca Paris on drums)

“So off I'm playing and touring for two years with all these people,” he sighs. “And so then, boom, in 2013, I started my album. But even then, I needed money to go to the studio, pay the musicians, so I needed to work more. So it took years until I finished the album last year. And all that time to focus. To make the decisions. So all in its right time.”

The album, D'Alma, was completed and released in late 2017. D'Alma, in Portuguese, means “My soul.” Why?

“Because every time I would sing 'Ninguem,' people would say this is very deep... it comes from your soul,” he answers. “And when I play percussion, people always say, 'Oh, it's from your heart, from your soul.' So this was here and I knew it had to be the title of the album. It's not a song, it's the whole album.”

“Ninguem” is actually an old Cape Verdean song he fell in love with as a boy, written and first performed by Gerard “Boy Gé” Mendes, who was from Senegal then moved to Cape Verde.

“After those first few shows in 2009-2010, I came back to Portugal, and kept saying to myself, 'I have something here,'” he recalls. “So now I needed a song. But I had no original composition yet. But since I was born, there is this song playing in mind. It was recorded back in like 1979-1980. So I started playing this song at home, and my granddad said, 'Hey, what is this song?' And I said, 'Oh, it's just a song.' He wouldn't say that he liked it, of course, but I knew just him telling me that, that it was something. So I start going to a few bars and I'd sing it, 'Ninguem, ninguem, niguem....' It means 'nobody.' I needed this song to get in and provoke people to talk the next day, to tell their friends, and so on and so on, so they would invite me again the next day to sing it. And so this was it.”

Miroca Paris – Ninguem (Live, 2015)

“'Ninguem' is special,” he continues, “because it puts me in the tradition. But then I needed something, you know, for my first single, to make it official. And that became 'Mund Amor' [World Love],” he says.

Miroca Paris – Mund Amor

“Then, I needed something with rhythm, O.K.? So I wrote 'Nhe Simpronia.' It's a story of a lady who lives in Cape Verde. 'Nhe' means 'Miss' in Creole, so it's 'Miss Simpronia,' her name. Whenever I was there, I would spend a whole day talking to her. She would just gossip, like, 'You know that guy was 92, he died already, and maybe next time you won't find me because I'm old too.' And I'm like, 'No, no, no.... Of course you'll be talking, telling me stories about everything going on this street, on that street, or what happened to this guy or that.' So I wrote this song about her. And she's still alive. I told her that this is my homage to you.” He then laughs, adding, “She even has Facebook and talks about it. Can you believe it?”

Miroca Paris - Nhe Simpronia

The album features several musicians from Cuba, and we wondered how he decided to introduce their sound into his.

“Well, back when I was with Cesaria,” he explains, “three of her musicians were from Cuba. One of them was my roommate when we toured and he would bring me many discs to listen to, and I would bring him stuff from Cape Verde. And for years we would do that. I learned from him a lot of names, rhythms from Cuba. So I always wanted to have this sound.

“When I started doing the songs for the album,” he continues, “I prepared all the basics in Cape Verde rhythms, like the percussion and guitars. Then, I started to paint with color. Like you're doing food – a little paprika from India, a little something from Malaysia, a little bit of something from Brazil. This was the amazing part. But then you have to have the skill for what amount of the ingredients. It's the more serious part. Not too much, not too little. I knew exactly what I wanted.

“Everything I do starts from the rhythm,” he concludes, “and then it's easy to put the melody and harmony there. It makes sense. This is how I think and how I feel.”

Related Audio Programs