In January 1992, three hand grenades were thrown into the office of promoter Attie Van Wyk in Johannesburg, South Africa. Fortunately, nobody was killed, but why did it happen? This action was in reaction to Paul Simon’s having broken the cultural boycott against the South African apartheid regime in the creation of his groundbreaking album, Graceland. Simon himself had been put at the top of the assassination list of AZAPO, the militant Azanian People’s Organization.

Much ink has been spilled in trying to unravel the conundrum of why Simon flouted the boycott. After apartheid ended, Mandela had his hands full with the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, so he doused out this music conflict quickly by knighting Simon’s collaborators (in both senses of the word) Ladysmith Black Mambazo “South Africa’s cultural ambassadors.”

Let us mark Graceland’s 35th anniversary by discussing the origin of gumboot dance and the meaning of the gumboot itself in South African racial politics.

Between 1956 and 1968, 40 African countries threw off white minority rule and adopted varying forms of majority rule. How was it that South Africa escaped this widespread transformation for another 25 years? The answer may not be visible on the surface, but rather two and a half miles underground. South Africa has the world’s six deepest mines, and they are all gold mines. For superrich “Randlords,” it was like living in a penthouse on top of Fort Knox. No way in hell you are going to let the folks in Muldraugh, KY, grab the gold. Extreme control of mine labor was essential in this; Prime Minister Barry Hertzog set the tone decades before:

“…‘uncivilized labour’ is work done by persons whose goals or aim are restricted to basic necessities of underdeveloped and ‘savage’ people.”

Going back to the 19th century, Black gold miners were sent deep underground by their white masters. In order to keep them working nonstop, the masters shackled the Blacks to their work locations in chains, and in order to avoid rotting feet from constant water flowing on the ground (and thus lowered productivity), they were given high rubber galoshes, known as gumboots. Strikers were killed by the police. The masters beat the miners savagely if they dared speak to each other, so the miners, who had been recruited from various linguistic regions, communicated with each other with a kind of Morse code of stomping or slapping the gumboots and clanking their chains.

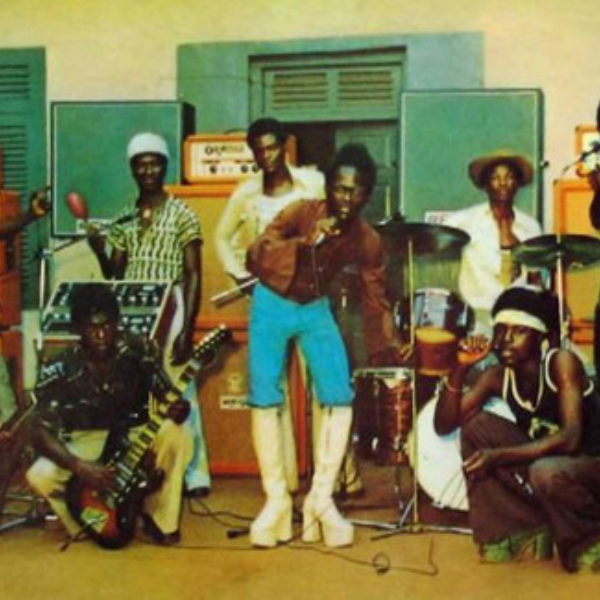

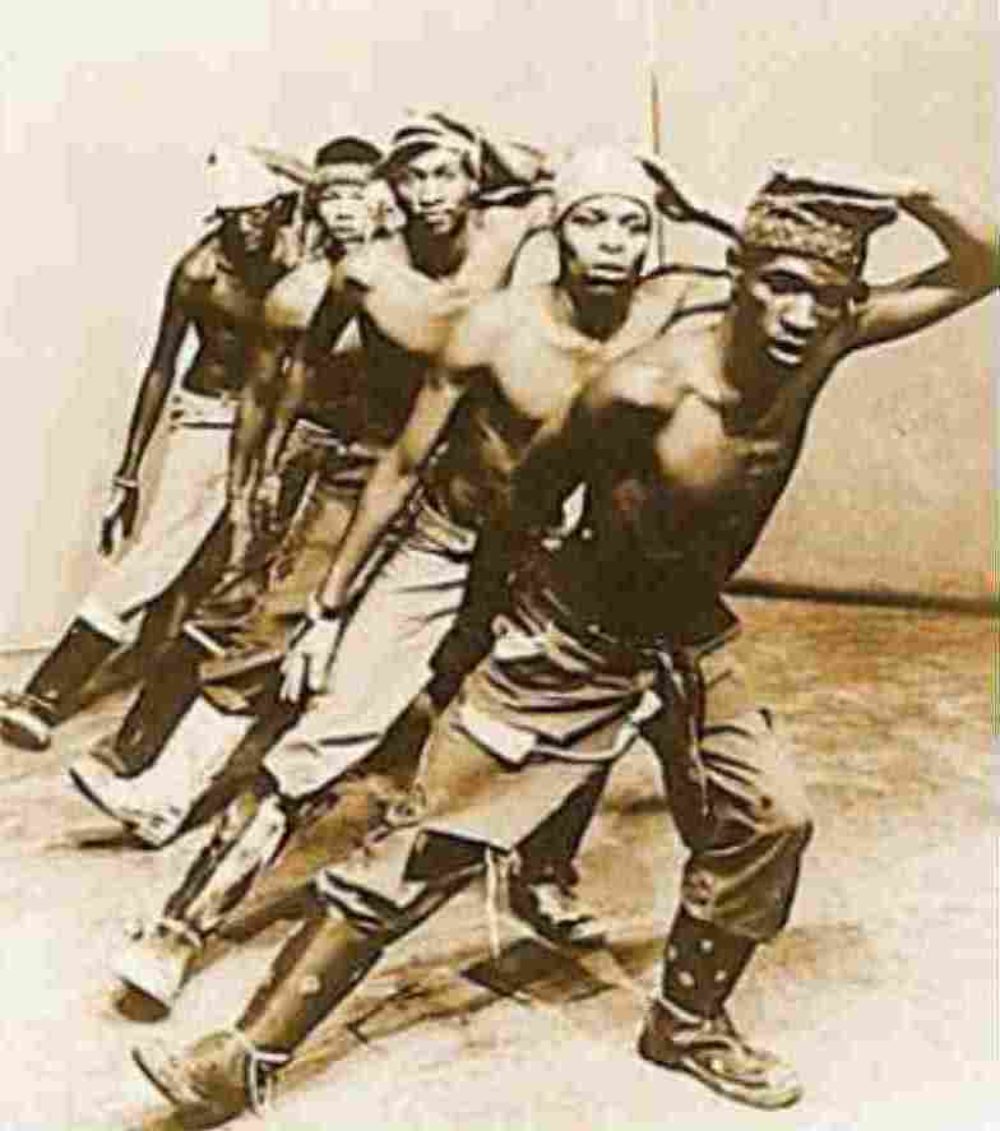

Anatomy of A Song pointed out in our piece on “Zangalewa” from Cameroon here that victims of colonial oppression often represent the oppression symbolically in various forms of cultural expression. Beginning in townships during the 1970s, this is what happened when a new dance form was born, the gumboot dance, which often parodied the behavior of the white masters; two dances were named “Police” and “Salute.” You will note in the picture above the thin wire ankle bracelets. The sound of the clanking chains from the mines had been replaced symbolically with bells or bottle caps attached to the anklets.

Gumboot dance was so popular in South Africa, one troupe which had formed at a youth center, the Rishile Gumboot Dancers of Soweto, was good enough to graduate into a full-scale musical,Gumboots, which toured England and the United States in 1999. Here is a short video about the production:

In the years preceding Graceland, Paul Simon had eagerly explored musical idioms other than his brand of folkie pop: from a pilgrimage to legendary Muscle Shoals for There Goes Rhymin’ Simon, to Kingston, Jamaica for “Mother and Child Reunion,” to launching many a subway busker blowing Andean wind instruments with his “El Condor Pasa.”

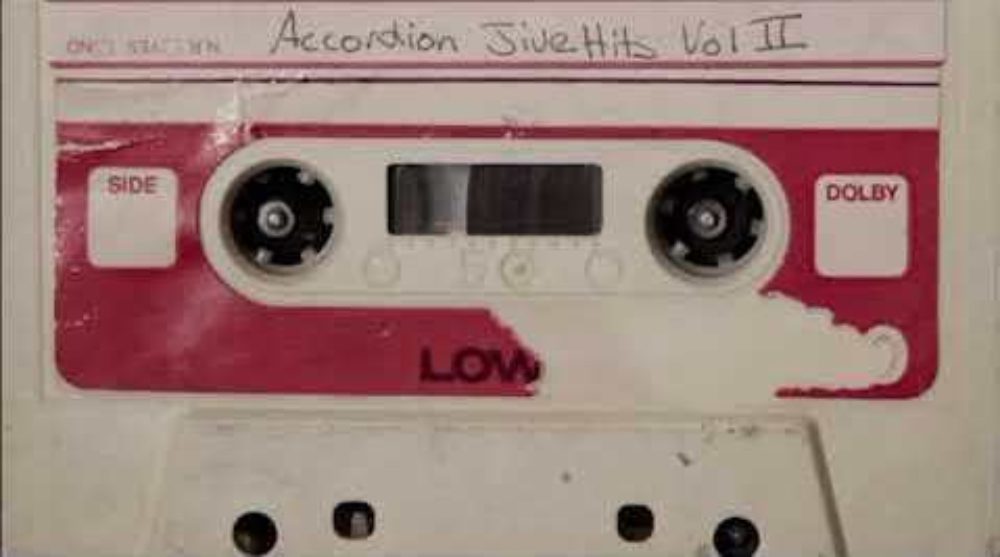

Gumboots, as it turns out, were key in Simon’s first interest in South African music. Network TV producer Lorne Michaels’ second show had been cancelled, and he dispatched his now-unemployed music producer Heidi Berg down the hall in the famous Brill Building to seek work with Paul Simon. She handed him this mixtape:

Simon immediately fell in love with the mixtape, and in fact never gave it back to Berg despite her pleas. Other than Simon indicating that his favorite track on the tape was “Gumboot” by the Boyoyo Boys, no one will ever know what else was on the tape. What really counts is the musical styles which most attracted Simon and the specific artists he brought into his Graceland collaboration. So, let us explore further.

Graceland takes a lot from two South African township idioms, isicathamiya, an a cappella Zulu tradition, and mbaqanga, an infectious danceable style with Western instrumentation. The Graceland album was produced in three locations: first at Ovation Studios in Johannesburg, then at Penny Lane Studios in London, and then further work and final touches at the Hit Factory in New York, NY. The initial Johannesburg sessions were entirely in the mbaqanga style.

South Africa’s music scene at the time mirrored many other aspects of the racist apartheid system. Whites controlled the record industry and radio. Songs and song titles were heavily edited. Many Black artists kept in their lane and just performed pop song imitations of foreign hits. Black producers were few and far between. When Black musicians somehow recorded a cover of The Melodians’ “Rivers of Babylon,” it only got through because the apartheid censors lacked the intelligence to understand that South Africa was perhaps the best-suited referent for the song’s Babylon metaphor anywhere in the world.

America’s rapacious recording industry has a sorry history of ripping off Black songwriters by paying pennies for publishing rights, especially to the geniuses of blues and rhythm & blues. But long before Graceland, one of its octopus arms had already reached out 8,000 miles to South Africa, from where it famously stole Solomon Linda’s “Mbube,” music-laundering it into “Wimoweh” for Pete Seeger, the Kingston Trio, and the Tokens (for whom it hit number one on the Billboard Top 100), and then further laundering it into Billy Joel and N-Sync’s “The Lion Sleeps Tonight,” eventually helping the Walt Disney Company make a total of $9 billion from its The Lion King movie and stage blockbusters. The entire money grab was based on a patently false claim the song was “traditional” and on using two phony made-up names for arrangers. Only after decades and legal battles did Solomon Linda’s descendants receive royalties which amounted to exactly 0.00000001% of Disney’s profit rake-in. Socialist folkie Seeger in his day had mailed $1,000 to Linda and told Folkways Records to pay his share of earnings to him as well, but never checked to see if Folkways actually followed through on that, which it appears they did not.

Paul Simon was an ultra-rich superstar, but smart enough to know the optics of his boycott-defying adventure could get immeasurably worse were he to follow white America’s M.O. for Black songwriters. South African musicians at the time were paid about $15 an hour for studio work, but Simon paid each of those he worked with $200 an hour—three times the top New York City rate. He also gave co-writing credits and presumably royalties to five of his South African collaborators for five songs on the Graceland album. He ended up employing 17 individual Africans including Youssou N’Dour from Senegal, and two ensembles, the Gaza Sisters trio and the considerably larger Ladysmith Black Mambazo. In addition to working on the album, many of these artists also toured the world doing arena shows in the late ’80s and early ’90s and reunited in 2012 for numerous concerts celebrating the album’s 25th anniversary. Simon, it’s reported, made a point to take no money until the entire entourage got their full contractual fees.

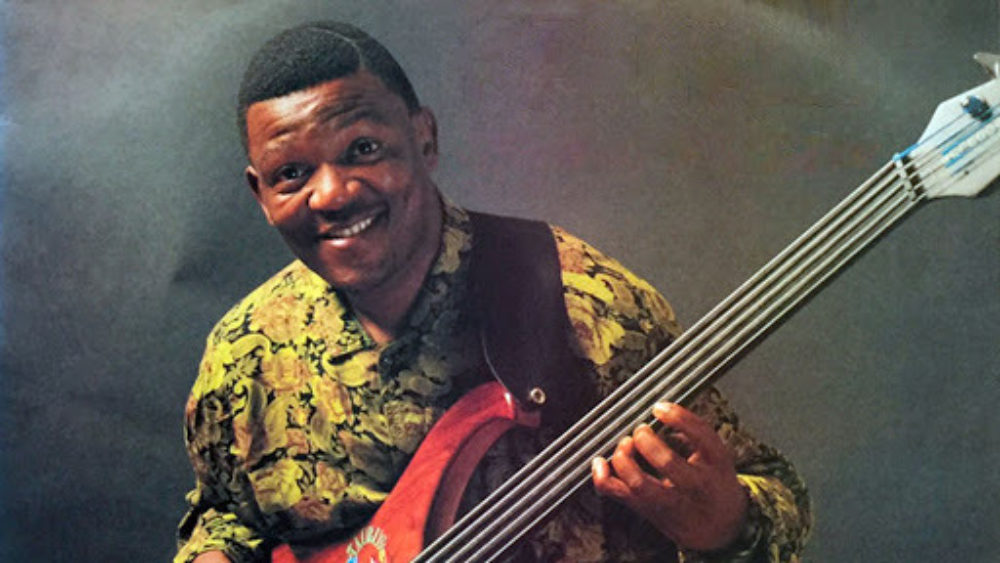

Anything known as “Accordion Jive” was squarely in the mbaqanga style, a rhythmic, danceable sound that had been influenced by big band swing. Exiled singer Miriam Makeba sang in mbaqanga style. Before coming to South Africa, Simon had tried to buy the rights to “Gumboota,” as he had with “El Condor Pasa” in the 1970s. Simon’s label was Warner, and its South African producer was Hilton Rosenthal, who was also Johnny Clegg’s producer. Rosenthal’s instinct for Black South African music derived from his partnership with Keloi Lebona. Graceland bassist Bakithi Kumalo says Lebona was

“…our Quincy Jones of the township … that man is the one who called us and said, hey, look, there's a guy from the States doing this recording …He used to find musicians to record with Hilton …because Hilton really knew about the good music.”

Rosenthal had urged Simon to produce an album of South African music instead of buying rights and had sent him dozens of records to listen to. Simon shared credits on his own “Gumboots” with Johnson Mkhalali and Lulu Masiela from the Boyoyo Boys. Here Mkhalali’s 1985 “Sunshine Boots” surely demonstrated some of the best township accordion jive:

This is the first verse of Simon’s version of “Gumboots:”

I was having this discussion

In a taxi heading downtown

Rearranging my position

On this friend of mine who had a little bit of a breakdown

Here is Simon’s “Gumboots,” from Graceland’s 25th Anniversary tour in 2012. By this time, Simon had replaced Johnson Mkhalali on accordion with a Cajun musician, Alton Rubin.

In Simon’s lyrics, there’s no mention of the horrendous suffering of the miners who’d actually worn the gumboots in the lyrics. As mentioned above, Simon was under fire (as literally was his South African promoter whose office was detonated with hand grenades), for his flouting the cultural boycott. Likewise, there was also much displeasure with Graceland’s apolitical lyrics. Though one of his earlier songs, “The American Tune,” does lament: “My eyes could clearly see the Statue of Liberty sailing away to sea,” Simon often asserted he would leave political songs to those who have great talent for it, such as Bob Dylan. Simon made this pronouncement:

“Authoritarian governments on the right, revolutionary governments on the left--they all fuck the artist. What gives them the right to wear the cloak of morality? Their morality comes out of the barrel of a gun. Try and say bullshit on their government, write a poem or a book that's critical of them, and they come down on you. They make up the morality, they make up the rules.”

Overall, Simon was more or less nonchalant about flouting the cultural boycott. He did reject many lucrative offers from white-owned luxury resort “Sun City”—unlike many American musicians who took the cash—and asserted he was only in Johannesburg to give work to South African musicians, paying them handsomely.

The counterintuitive relationship between Graceland’s music and lyrics could then be viewed as a kind of postmodern pastiche, much like, by way of example, Moulin Rouge’s relationship with the classical Hollywood musical.

Another township accordion maestro who contributed to the Johannesburg sessions was Forere Motloheloa from the Lesotho-based band Tau Ae Matsekha. His “Ntate Li Busetse” is also a good example of township accordion jive:

Forore co-wrote and (along with Tau Ae Matsekha) performed on Simon’s “Boy in the Bubble.” Only a year after Graceland’s release, with apartheid rule still firmly entrenched, Simon and his South African musicians were back in Southern Africa, but right across the border in Harare, Zimbabwe. Bakithi Kumalo describes the event:

“The concert in Harare was the best concert. It connected all of southern Africa. Mandela was still in prison, and …people like Hugh Masekela and Miriam Makeba, they couldn't come home, because they were still in exile. So by playing in Zimbabwe, it opened the doors up to say, look, our big music is coming here. And it’s coming in a big way that nobody can stop it. Because we came in very strong. And the people they came from all over the place …thousands of people never paid to get in …the whole village came to the concert. And then four years later, Nelson Mandela was released.”

Another big township jive band was General M.D. Shirinda and the Gaza Sisters. Here they are in 1985 singing “Ndi Xitwile Xirilo Xa Wena:”

Simon’s “I Know What I Know” was based on music from an album by Shirinda and the Gaza Sisters, and Simon gave Shirinda co-writing credit. Again in Harare, Simon performs the song with the Gaza Sisters but without Shirinda:

March 25, 1985 was the 25th anniversary of the Sharpeville Massacre of 300 Blacks. On that day, while Simon was in South Africa, the South African Police perpetrated the Langa Massacre, killing 35 funeralgoers, mostly shooting them in the back with live ammunition. The local racist thug government had gone completely Orwellian, issuing orders banning all weekend funerals followed immediately by orders banning all funerals except those held on Sundays.

The tension was extremely high, and this was felt in the studio. Every afternoon as white curfew on Blacks approached, the musicians started getting worried about getting home without being arrested. Kumalo, whose young cousin was one of 700 murdered by police a few years earlier in the Soweto Uprising, remembers:

“…of course, you have to be nervous …you have to follow the rules …you better get out of there before it gets too dark. Because that's when the police start driving around telling people you are not supposed to be there. Why are you there at this time?”

Simon determined to leave South Africa, having only cut five tracks there, resuming the recording sessions in at Penny Lane Studios in London. Simon had met Joseph Shabalala and Ladysmith Black Mambazo (LBM) while in South Africa, and London would be his opportunity to work with the South African musicians most associated with Graceland’s unique sound. At this point, Simon was moving from the mbaqanga idiom into the isicathamiya idiom.

Isicathamiya is an a cappella style with tightly choreographed dance moves that emerged in the 19th century, which is believed to have been in part inspired by American minstrel shows and ragtime vaudeville groups that toured South Africa in the 1860s. Like mbaqanga, it came from South African townships. It was so popular that competitions were held every Saturday night from 8 p.m. to 8 a.m. between the many choirs, all dressed in suits, white gloves, white shirts, shiny black shoes and red socks.

Ladysmith is the township from which LBM came, Black represents the black ox, the strongest farm animal, and mambazo means axe. The group came up with the name because they had chopped down so many of the other groups in these contests, they were banned from competing anymore, and only allowed to perform.

People supporting Simon argued “He was exposing these musicians who are unknown around the world.” Trombonist Jonas Gwanga argued against that, saying “So, it has taken another white man to discover my people?” Both arguments are wrong. LBM had been around for decades already when Simon invited them to collaborate. They had toured Germany twice and had a following there. Harry Belafonte, whom Simon consulted before going to South Africa, points out that foreign Blacks were only permitted to enter the country if they were bonded servants of whites, so perversely, only a white person like Simon could perform this kind of talent export.

Simon must have heard tracks from LBM’s 1981 Phansi Emgodini album, including “Khwishi Khwishi:”

One of Graceland’s most unforgettable tracks is “Diamonds on the Soles of Her Shoes,” co-written by Shabalala. Its refrain “Ta-Na, Na-Na-Na” is taken directly from LBM’s second recording in the late ‘60s. Again, from the 1987 concert in Harare:

While “Gumboots’” lyrics steer far afield of the political meaning attached to the word, with “Homeless”—also co-written by Shabalala—there was something approaching equivalence. The song derives from a traditional Zulu wedding song whose lyrics suggest the newlyweds may have so little money, they might have to sleep on rocks. The words “for better or for worse” immediately come to mind. In a society oppressed by colonial powers for centuries, for the oppressed, the “worse” might be more likely for any young couple. The song’s lyrics are not about weddings, but “Webaba silale maweni” does translate as “Let’s sleep on the rocks:”

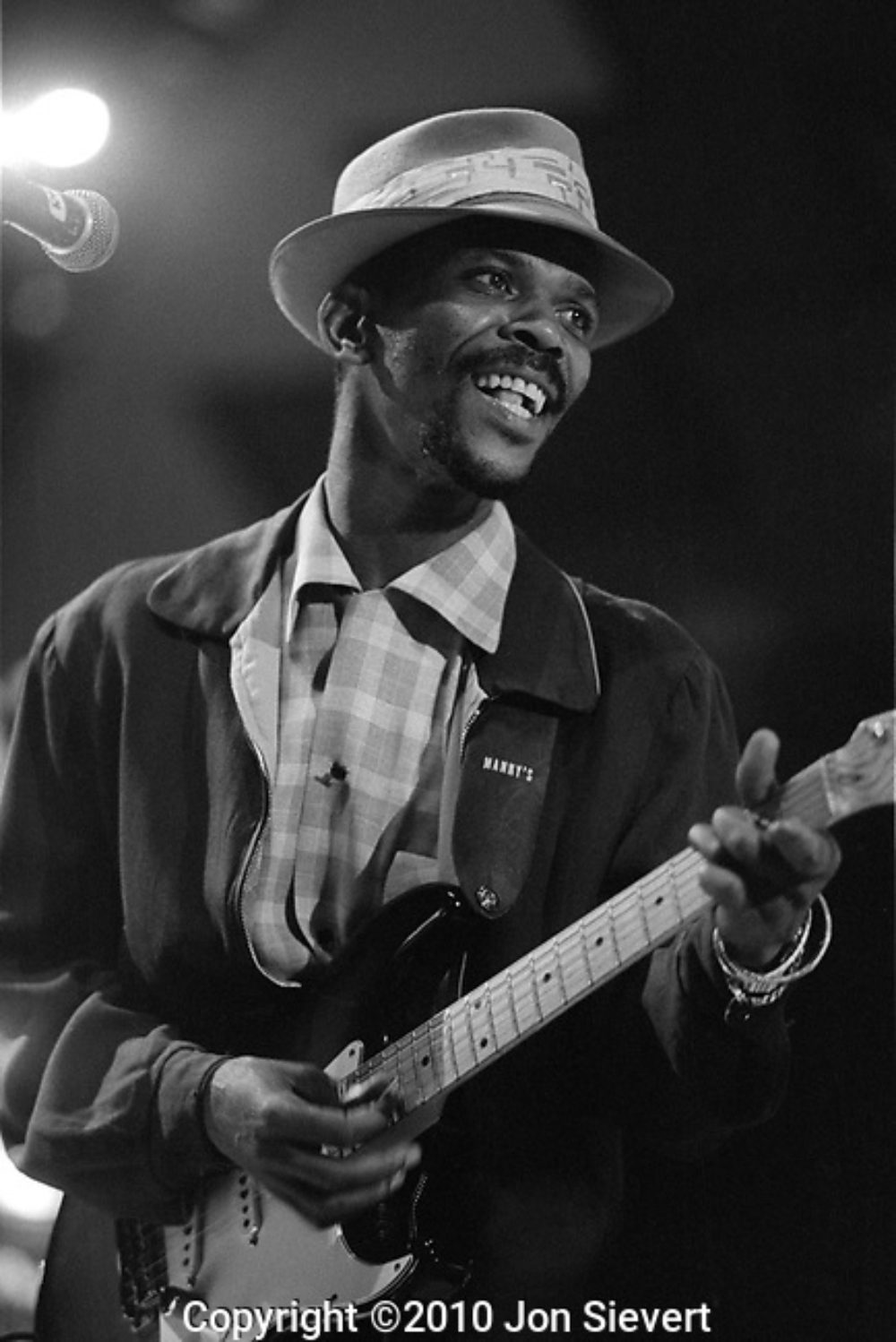

Consummate rock critic Robert Christgau said of Graceland “…it boasts a bottom. For Simon, this is unprecedented. Graceland is the first album he’s ever recorded rhythm tracks first, and it gives up a groove…” Long-exiled Hugh Masekela was still revered in South Africa, and interestingly, Graceland’s bottom was essentially populated with jazz musicians: Ray Phiri on guitar and Isaac Mtshali on drums, both from the Afro-fusion band Stimela, and studio musician Bakithi Kumalo on bass. Another instance of Simon’s pastiche technique.

Among Simon’s vast South African entourage, Phiri is the only one to complain about credit: “There’s bad blood with Paul Simon. He never gave me credit on the album for the songs I wrote.” Phiri claims his father taught him the title track melody, which he gave to Simon. Another unhappy camper was Heidi Berg, who’d said “Where is my end?” for having given Simon the mixtape that first inspired Graceland.

Here is a Stimela recording of “Fire, Passion and Ecstasy” from around the time Simon came to Johannesburg:

Just before Simon came to South Africa, Kumalo had done his first solo effort, and here is “Step On the Bass Line” from that album:

Paul Simon could not employ every talented musician in South Africa. One does wonder what happened when the discussion turned to Mahotella Queens, Johnny Clegg, Abafana and others.

Graceland sold 16 million copies around the world, went platinum five times in the U.S., won the 1987 Grammy for Album of the Year, the 1988 Record of the Year, and was added the United States National Recording Registry as “culturally, historically, or aesthetically important.”

Huge thanks to:

Bakithi Kumalo for his June 15, 2021, interview

Robert Cristgau for his “South African Romance”

Jordan Runtagh for his “Paul Simon’s ‘Graceland’: 10 Things You Didn’t Know”

Sam Cullman for his The Lion’s Share

Jeremy Marre for his Rhythm of Resistance

Joe Berlinger for his Under African Skies

Aubrey Powell for his The Gumboots Story

Rian Malan for his “In the Jungle: Inside the Long, Hidden Genealogy of ‘The Lion Sleeps Tonight’”

Andrew Donaldson for his “A return to Graceland”

dj.henri is a New York City DJ who has performed at the Apollo Theater, B.B. King’s, Symphony Space, and elsewhere. He is also the creator of radioafricaonline.com.