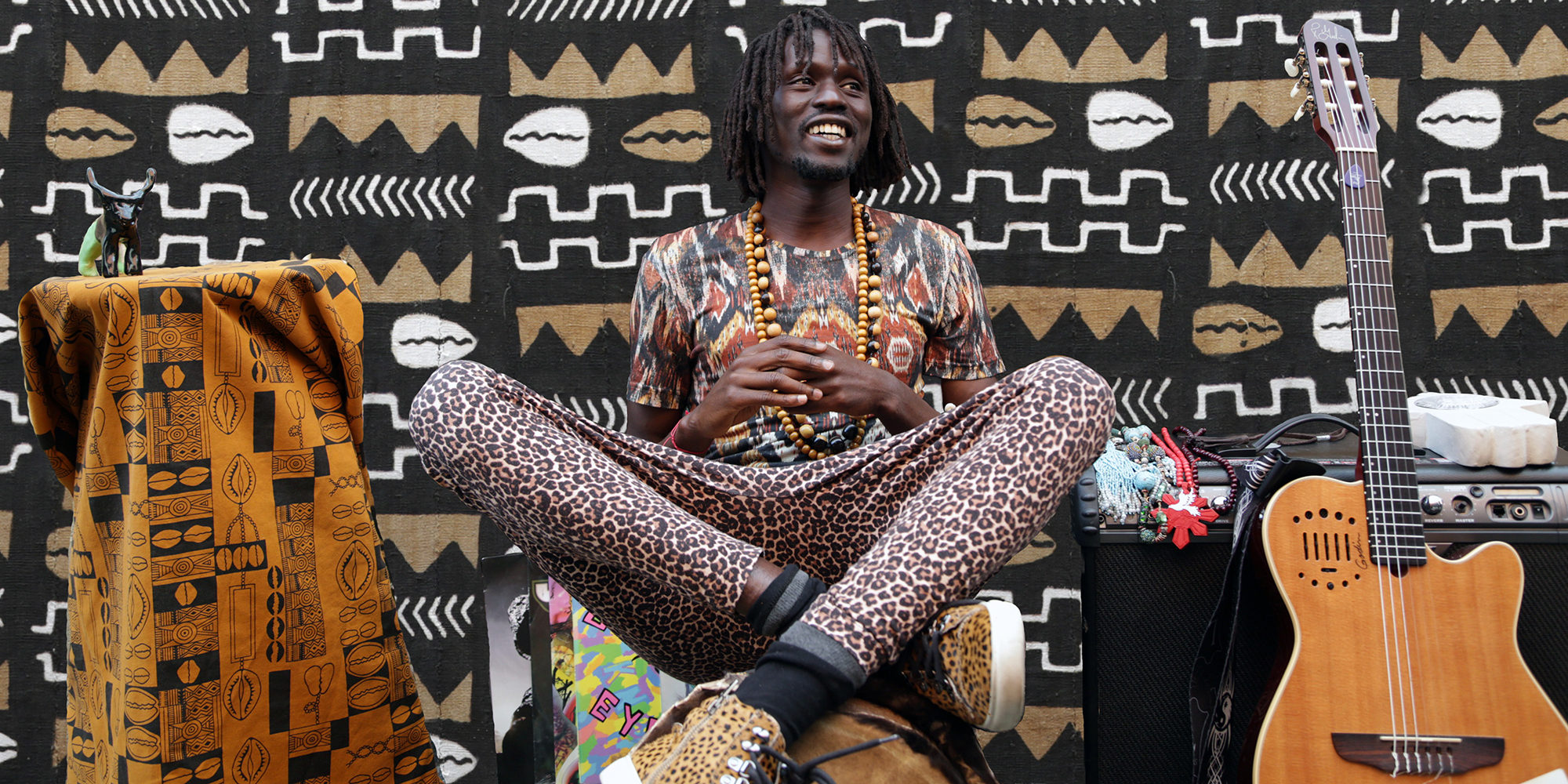

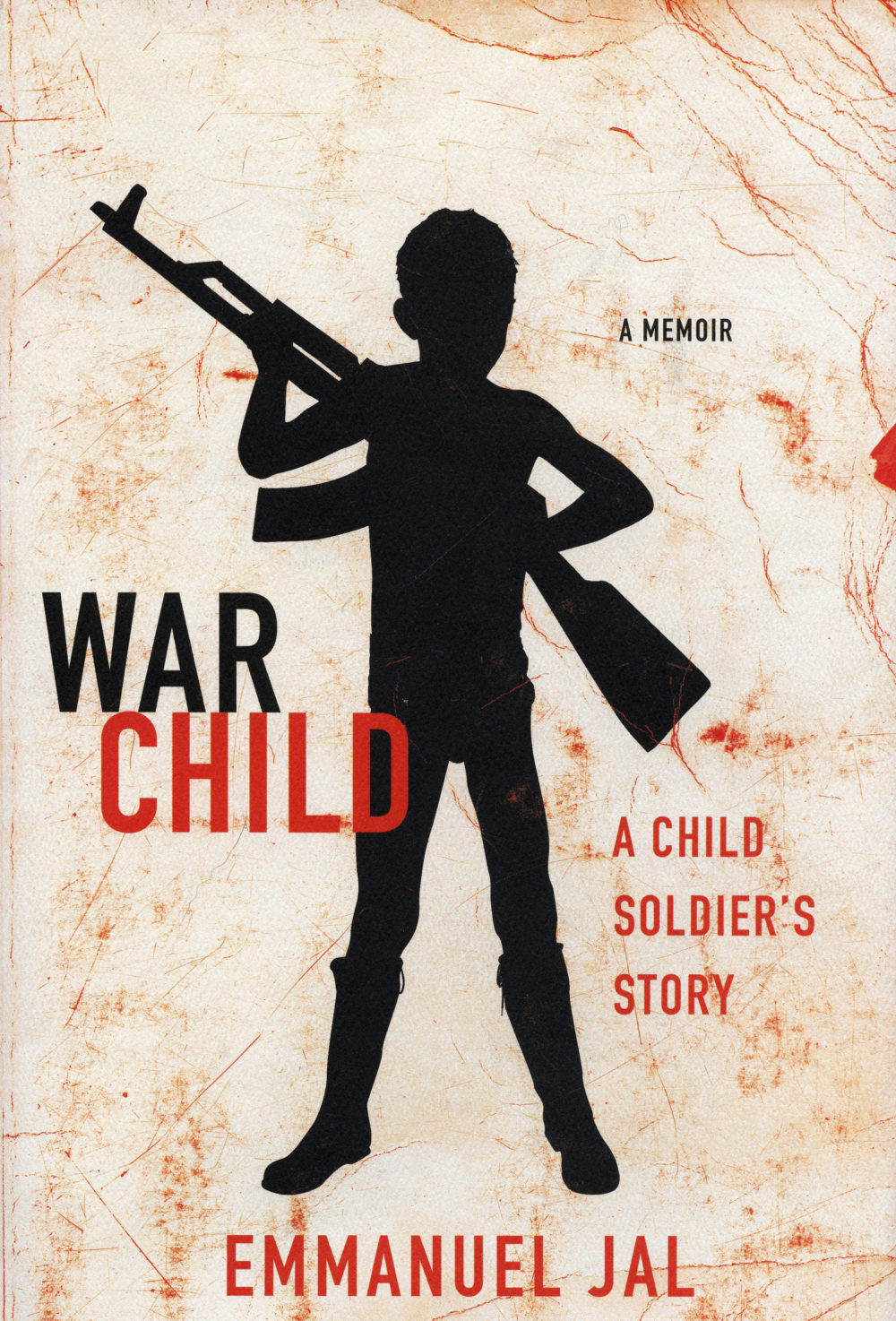

Emmanuel Jal is no stranger to longtime Afropop listeners. Jal hit the scene in 2008 with the album War Child, and accompanying autobiography of the same name recounting the harrowing tale of his escape from life as a child warrior in South Sudan. From the word go, Jal was a free spirit, remarkably poised and light-hearted and able to combine hip-hop, classic Sudanese music, rock, folk and whatever other genres interested him. His albums are all unique and absorbing, and he is a force on stage. He is also a powerful storyteller and motivational speaker who has inspired young audiences around the world. Since 2012, Jal has made Toronto his home. Banning Eyre reached him there by Zoom to hear more about his Canadian life. Here’s their conversation.

Banning: Emmanuel, so good to see you. So here's the story: We’re doing a show about the African music scene in Toronto. I didn't even know you lived there, so let's start there. How long have you lived in Toronto?

Jal: Oh man. Since 2012. This has been my base here.

Why Toronto?

Well, you know, I used to be in England. Then I decided to move to South Sudan, and then when I arrived there, the welcome wasn't that great. So I did a peace concert, because I'm an activist. I was told, "We don't like activists." I was beaten by police at night till I blacked out. I had a choice. It wasn't a safe place to be. So I said, Okay, let me get myself a base where I can really focus on music and do my work. And my visa was no good in England. Then Canada came told me, "Hey, we like people like you. Come over!" That's how I came to Canada.

That's interesting. I know a bit about Canada because I grew up there in Montréal and my sister lives in Ottawa. They have very different attitudes towards people in your situation than, say, our country down here.

Yeah. It's amazing. To me I always think Canada is heaven. Seriously, Canadians have no idea. The places I've been... Canada is heaven.

Coming from you, I believe that. So it feels like home now?

It's home. The thing I would say is when you are a refugee, it takes you 13 to 15 years to become mentally stable. Because your heart is back at home. Your mind is elsewhere. So to actually focus in one place and do something is the challenge, because 24 hours you are living in the past and in the future, and how you really want to be part of helping your people. So it's been a challenge for not only me but a lot of refugees. But I've managed to use my focus to do something.

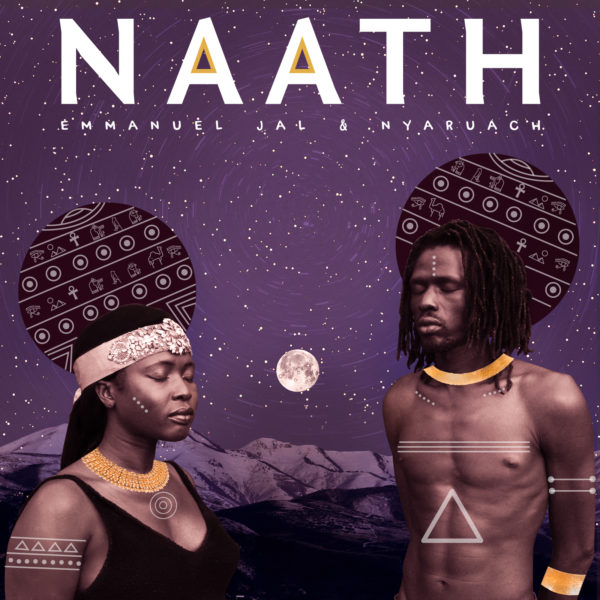

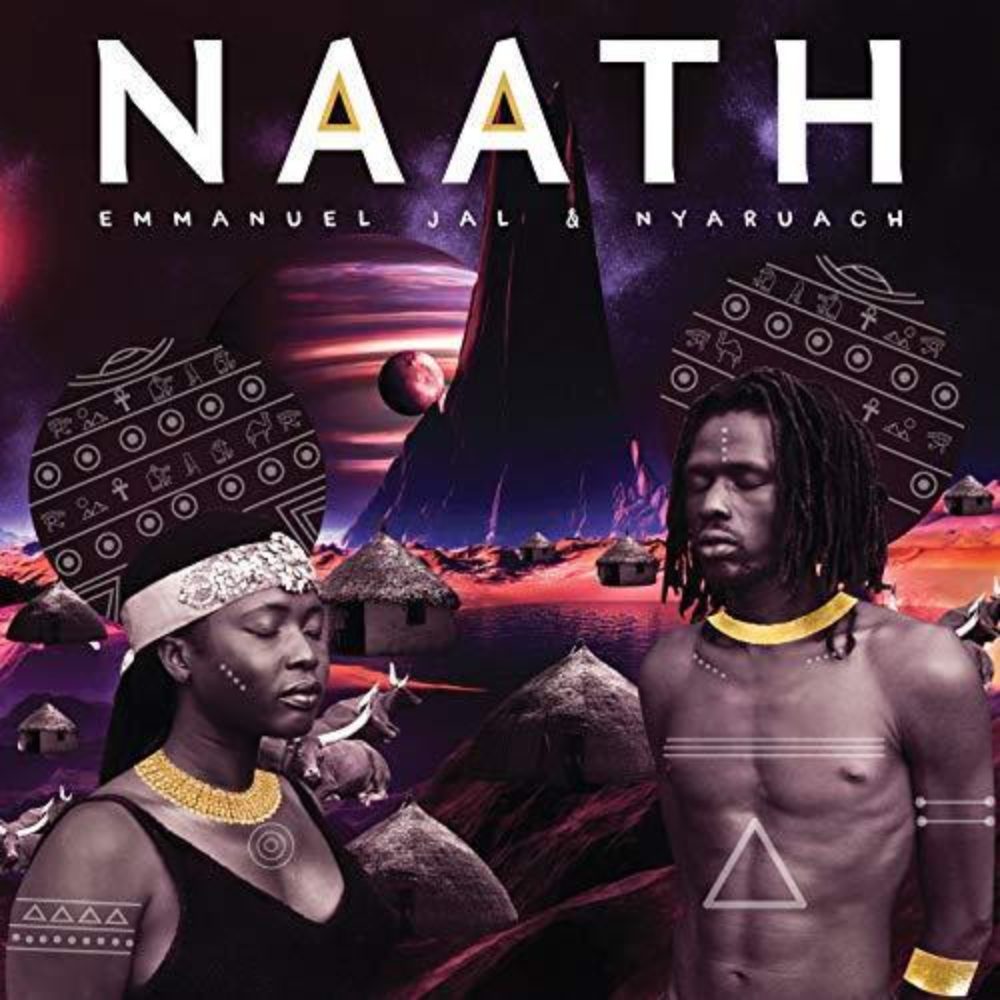

You sure have. I really enjoyed your last album, Naath. And I hear you're working on a new one now.

Yes I'm working on a new album. Similar take. But there's one track that I'm bringing a style that only exists in the village, a kind of style that's almost like hip-hop, but it's hip-hop. It's a style where you are in love with a girl and you go to her house with your friends and freestyle until morning. And if a girl likes you, she comes and talks to you. If the mother comes and gives you water, you don't drink it. If the sister comes, don't drink. Whatever they bring you, don't drink it. But if the brother or the uncle or the father comes, run away. Any man that is coming, run! If the girl comes, it’s good news. It means the family likes you.

But don't drink the water.

Don't drink the water. If you drink the water, you become a family friend.

Are any of those tracks ready to be heard on the radio?

There are some that are ready. There's one track that is released now called “Chegu,” which has two remixes. And some of them have gone on top of the charts in the dance clubs. The European ones.

Tell me about it.

So this “Chegu” is something like “I've let go.” It's basically forgiving and starting fresh. And so it's part of the line of kindness. Don't confuse kindness with weakness. So it's basically about sharing the profit that you get when you let go and forgive. You look at things in a different way. That's what the song is all about. You can actually get it on Spotify right now.

Let's talk about your 2018 album, Naath.

It's an album that I put a lot of work into. Most of the work was done online in Toronto here. And then I did some work back in Kenya where I could meet my sister. Some of those authentic voices, you can't really find in Canada.

Where is your sister now?

She's in the U.K. But at that time, South Sudan was at war with itself again. So what I did with my sister was, “How can we still communicate as artists to show a positive side and write songs about the future?” You know? Enjoying the future now. Because most of the time we complain about now, but we never write about the positive things that we have, so that we can begin to program ourselves for that world we want. She was in the refugee camp and I was in Canada, so we put our voices together with other young South Sudanese who were there. That's what it was all about.

There are also songs about being positive. There's that song “Ti Chuong,” which means “you have a right.” And if you have a right, whatever it is you're hiding that is bothering you, if you share it, you find that you have a right. So come out. Heal yourself.

I remember the story about how you were separated from your sister for a long time. But she's landed in the U.K. now. She's doing O.K.?

Yes. She is there. You know once you are in most of the Western countries, there's that safety. No one is going to bother you. It's definitely not a place where a bomb could drop. The only thing that we never worry about is this Western disease called stress, this mental illness where you have like… You're getting angry. For what? Something is bothering you in your head. You just get this anxiety. The Western diseases are completely different than those in the refugee camp. Once you get this anxiety and illusion of something that's crushing your chest and your brain. These are the new things that we just have to cope and learn how to survive here.

That's interesting. The singer Blandine was just telling me that the difference between being a musician in Africa and in Canada is that you have so many things to think about in the West that you get distracted. It's hard to focus on music. That's why she said the musicians in Africa are better, because they just get to play music all the time.

They make the music, but there's not that anxiety and stress. There's something in the West; I can't seem to explain it. It's like something is trying to squeeze your head, to find a way to breathe… O.K., I got it. I’ve got how the Western world is. The stress we have back at home connects you with yourself and others. The stress that we get from the Western countries disconnects you to yourself and others. And so that's the way I can look at it. You could be with people, but you’re alone. The way I can describe it is: You are in the jungle. A lion chases you, and then you survive. The next thing is there's a tiger, waiting for you. Now you managed to escape the tiger. You jump into the river and you’re swimming, and a crocodile wants to bite you. That's the way I look at this. There are so many things that in Western world where you can’t tell the voice of a hyena from a hippo. Everything sounds the same. Once you understand that, then you can begin to find your way to breathe.

This is a concrete jungle. And there is a real jungle. You can grab a banana in the jungle. You can eat a mango in the forest. They have an illusion back at home that this concrete jungle is heaven. Once they come, it's a completely different picture.

Do you find for you as an artist that the concrete jungle there in Toronto is a problem? Or is it just something you have to adjust to? Or does it give you a different kind of inspiration? What would you say?

Well for me, the greatest asset I have is that I always have joy and peace of mind. These are the two assets I have. And I can never trade them for anything. Because the more pain I get, the more difficult my environment gets, my joy doubles. So this is different from being happy. Happiness can be substituted by anger quickly. But joy is constant. And when you're facing something difficult, it increases. So basically what I've known within my journey, my survival, is once you know your purpose, it gives your life a meaning in every stage of suffering. And it will make you understand that suffering is essential, indispensable for growth.

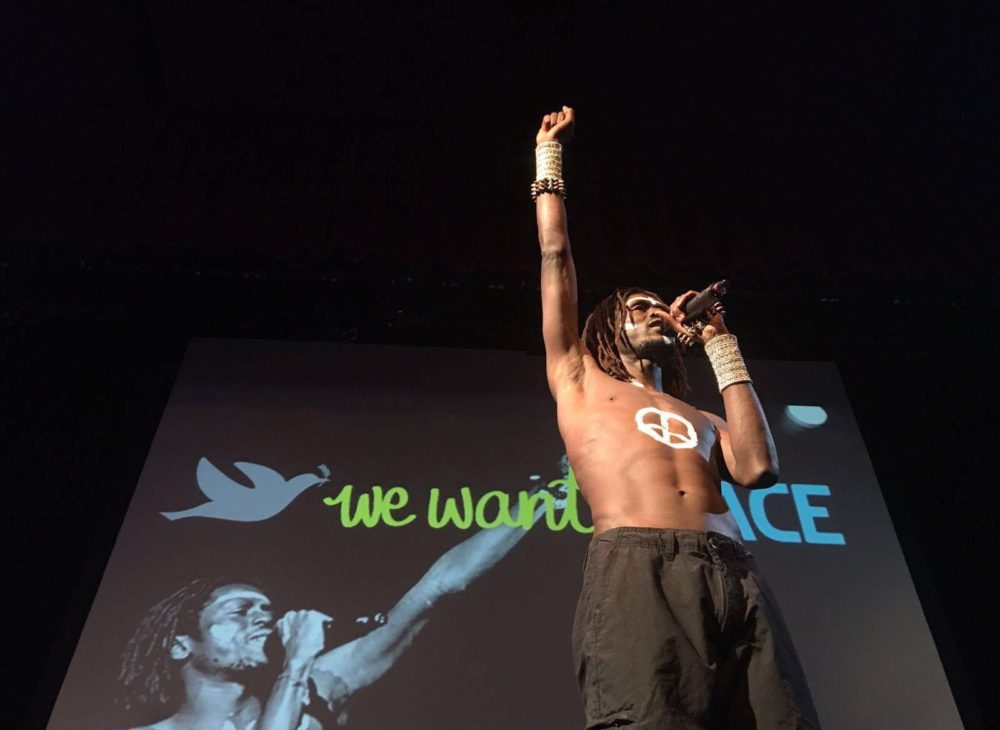

I'm in the middle of a pandemic. I'm a recording artist. But what we’re facing all of a sudden: the world doesn't see music as relevant. But they need it. They play it on YouTube and other places. But when you come and say, "Hey, how do we sustain our artists?" Oh no, they are not relevant. They are not essential. So everybody turns their face. Just imagine, the world without music for one week. What would happen? No music in the world anywhere. Talk show, no music. TV, no music. YouTube, no music. This world would just become dark in one day. It's an essential that is not seen by the masses unless it is missing.

One thing I've always admired about your music all the way back to War Child is that you seem to have a special kind of freedom. You're not limited to a style. I remember speaking with the rapper from Congo, Baloji, and he was telling me about his frustration at not getting accepted in the world of mainstream hip-hop, and he told me that hip-hop is the most conservative music he has ever dealt with. Which I thought was interesting coming from a Congolese musician. People think of you as an African hip-hop artist, and that's a description. But there are so many other things that happen in your music.

Yes. It's hard to put me in one box to say, you’re a hip-hop artist. What I came to realize is hip-hop can be integrated into all kinds of sounds. And I just want to have fun as an artist. Create what you feel, not be constricted according to the market and labels. Just create whatever thought broke into your head.

You see, we have three types of imagination. There’s authentic imagination. The authentic imagination is the imagination that teaches us how to think. Then there is synthetic imagination. The synthetic imagination is the imagination that is influenced by institutions, where you are taught what to think. And then you have both synthetic and authentic imagination combined. And that type of imagination takes you to a level where you take the rules where you are taught what to think, and apply the authentic imagination that taught you that they can put it together.

So the way I look at it is to say, hip-hop music is supposed to go this way, and these are the rules. But instead, you say I like this sound. I like “lalalalalala.” Can you put that in? So whatever I like I want to put it in the music. O.K., I just listened to Bob Marley. O.K. Can I get some African sound and have something like Bob Marley in it? Or Lucky Dube? Because I know what inspires me. I don't want to be just guided by one direction. Because when you are looking for the market, that's when you lose it as an artist. And you cannot go long. You just go by how it feels and that’s how you grow in it.

That's a nice formulation. And it's working for you.

How it works for me is this: Why was I musician? So if you look at it, I'm not a normal artist that was supposed to be an artist. I'm an accidental artist. Why was I doing music? I did it to create mental space. When a person is traumatized, when you go through a difficult and a sad life, art becomes the place that shows you there is something beautiful that exists on this planet, and that's when you find a beautiful picture somewhere that takes you on a journey. That's where you find a beautiful story that takes you on a journey. It's the last place that reminds you that beauty is still here. Heaven is still here. When I play music, it's a form of meditation.

I remember starting to try to create a song, in six hours of meditation. I will call it a meditation, because there are people who meditate, but when you go into a state of creation, time doesn't exist. It just goes. And for the first time, I felt relevant. I found a place. I found something. You know, because I used to have these traumatic experiences. I would have flashbacks of what happened in the past, and it would ruin the moment. You will be in pain. It breaks your soul.

I describe trauma as soul murder, mental genocide, an invasion of demons to occupy space in your mind. Anyhow, those flashbacks were ruling the moment. And through music, I was able to escape, and in that escape, I was able to find beautiful memories that I can carry with me in the moment. So as I exposed myself, then I said, “I'm not doing this for the world. I'm doing this because I like it, first for me. I'm the first one to experience it.” I like it; I share it. But there is a different type of music where people create sounds for other people to listen. Those are different musicians. Here, I'm creating because I like it. And because I like it, how can I share what has made me happy?

If you're creating a joke... If you're a joke guy, you're the first guy to laugh at the joke. You find it so funny, and you go and share it. Now 10 people find it funny. But 100 people don't. So you crack your own joke in your head. Like when I create my music. The one that I really, really like a lot. Nobody likes it. The one that I created and didn’t give a lot of attention to. People like it. I say, “Why? They like that one but this is the one I like.” I want to create music I can dance to, music I can move my body to. That's it. If somebody else likes it, great. But if you're creating music for the market, now that's not being an artist. That's like being a commercial artist. You are creating according to expectations of whoever's listening. But the old-school artist just creates music. And that's why it's pure. That's why the sound is original. It borrows different influences.

There are a lot of commercial sounds that are built to go in a specific way, but they don't last. They won’t last for ages. If you look at music in the ‘60s and ‘70s and ‘80s and ‘90s, they last. Now we’re in generation where people are producing junk now.

What do you think of this new music coming out of West Africa, Nigeria, Ghana and places like that. They call it Afrobeats. Artists like Wizkid, Davido, Burna Boy. What do you make of that music?

I like their sound. It's their art. You know, what I tend to like about artists who are real artists... Let's say Michael Jackson. You can listen and tell he would like it. He would get something out of it. Bob Marley, the same. Real artists appreciate all forms of art and respect the other person's perspective. You want to see how they smile. Do they like it? Are they jumping? Are they enjoying when they're creating? When I look at Wizkid, are they having fun? Yeah! Then I go for it and I dig it. It's cool.

So that's what I look for. The ways I made my music in the past is I just created and didn't want any other people’s influence. But in the Naath album or the current music I make… Hey look, the beauty of music is to be able to open your mind to listen to people in the past and the present. So you can appreciate their sound on a subconscious level. When you begin to create, those voices, those sounds you listen to somehow influence you, and your mind will put things together to create something new. And so I feel like I was missing out. Now, I can sit down and just listen to Congolese music, or sit down and listen to Nigerian music. But I can say, I want to listen to aboriginal music. How do they sound like? O.K. I want to listen to Chinese. So now as an artist I began to appreciate how are they enjoying it. Some of this for fun. Or sometimes I just want to listen to classical music. Look at these artists. Are they really enjoy what they're doing?

Sometimes it's hard to tell.

But in the end finally you say, O.K. they’re enjoying it. You may not see it, but you feel it inside yourself. It's a language of its own.

Beautiful answer. Thank you. Let's come back to Toronto. How do you find it as a community, as a social world. I know there are these festivals that bring people together, but what do you feel about it as an African artist in a big Canadian community?

I mean, I don't know any other place where there's a lot of support for artists as in Canada. When you are an artist, and you’re serious with your art, there are many grants you can apply for. There are many people you can reach out to for support. You mentioned Nadine McNulty. One day she will be buried in Africa in a pyramid, as a remembrance. Because every artist who is African who has come here, Nadine has got their hand, showing them and guiding them and telling them, this is the way. I've never found somebody who really cared so much. Let's say an artist has collapsed in the hospital. Nadine will be the first one to be there and pass the information. If an artist is kicked out of their house, or an artist has no food, Nadine will pass the information faster. Sometimes you wonder. There are people in the arts who act like angels. They are people who do things because of media recognition. Then there are people who go beyond, and not posting on social media saying, "Hey, look I'm going to visit this artist who's been kicked out of their house and I’m bringing them food." Or, "I'm helping this artist with grants!" Nadine doesn't do that. She has that old school way of doing something from the heart without showing off.

So talking about the Toronto scene? There's a lot of beautiful music in Toronto, and actually they’re making it even better now with the initiatives to support more African artists to come out and see how they can bring their sound.

Is that because of the pandemic?

The reason I'm saying it's better this year is that there are more opportunities available if you know how to get them. If you know the right people to take you there. So there's a way in which artists can be supported to create.

The last time we spoke was shortly after you had had that experience of going back to South Sudan and, as you put it, not getting a great welcome. Have you been back since then?

I haven't been back, but I'm planning. Maybe I could go this year or next year. I want to create opportunities, projects that create jobs for young people. I want to go and say, "Hey, we should not just rely on government to provide for us. We have land. We can grow our own food. Why don't we plant cotton trees for the next three years? And then we don't need to import clothes. We can just go and grab the cotton and make our own clothes. O.K., why don’t we plant a lot of sorghum. Why don't we go to the old school where you have your own cows and you milk your cows and sell the milk, and sell our own cheese? Why don't we make our own cheese? There are illusions that have been brought to us by war and suffering, this idea that we are poor. We are not. It's just that people got lazy because we were given free food.

We put too much responsibility saying that the government should provide everything. No, it's the other way around. The government is as powerful as the people. We carry our dignity. But the action of the government is a reflection of the people.

Well, I hope you get back there. They could use a voice like yours. And I'm sure you have a lot of fans there.

Yes, they are always asking me to come back home. Sometimes they say, "Don't get into politics.” But I say, “Music is politics.”

You can't separate them. Is that what you mean?

When you're talking about music, if you talk about love, that's politics. You want a better policy with the person in your relationship with you. She broke your heart, you complain. Or you want to get with her, then you negotiate. So politics is part of our lives.

Tell me a little more about this album you're working on now. Does it have a name? A theme?

It’s called Shangah , which means “I am.” Or “I have been.”

That's different.

It's a word that has two meanings. We released a different version of the song on Spotify now. So we have the original version that’s going on the album, but we released a different version that is remixed. We have DJs who are excited about the sound I'm bringing. It's like they're discovering, so they like to make remixes. So some of them are like, "What have you got? Can we release this before the album?" So we give them parts.

How do you work when you record? Do you bring your band?

We have learned how to do low-budget production. So getting the whole band in the studio, that's like that could be 10 albums. You can go to one studio just to record one song and dream what you want to do. If you look at the budget for what you wanted to do, it would probably be 10 albums to come.

So you do have a band, but you don't bring them to the studio often.

Yeah I don't bring them much. I bring what I require. Most of the time nowadays you have a computer in your house, or a mini studio. You can literally play whatever you want to play.

But when you do play live, what's the band like?

In the future I want like a 12-piece band or 16-piece. You’d have horns, you'd have dancers, you’d have bongos, real drums, you'd have backup singers. A real show. But now you can only work with what you have. A DJ with backing tracks.

Any other thoughts about Toronto? Winter? How do you like winter?

Yeah, winter, it's something I had to get used to. I never used to like snow. And so what I did. One day I said, “Look, snow. You are here, and we’ve got to love each other.” So one day I just made sure nobody was looking. It was at night. I just jumped into the snow and rolled myself naked in the snow. And I felt the cold and went inside and I said, “This is it. We are now friends forever.”

Then I started studying snow. Why does it snow? And I came to realize that actually the snow does so many beautiful things. What stuck in my head is that out of every one flake, there's a tiny little organism inside. The snow becomes beautiful on the ground, but there's a tiny living organism, and it traps all of these things. It actually cleans the air and brings it down. Now, each and every living organism has got metallic enzymes, so if they come to earth and die, they are bringing iron, potassium, calcium back into that land. So I said, "Damn, this is amazing!" Going into underground rivers. It's amazing how the earth has got a way of recycling, distributing content.

That's beautiful, Emmanuel. I'm glad you had that experience. While I grew up with snow; I like it. But I understand it's a bit of adjustment if you haven’t experienced it as a young person. But I like your attitude.

When you look at the Canadian spirit, I said, “How do Canadians enjoy snow?”

Skiing. Skating.

So they are finding a way. Creating snow dolls. Now I kind of like once in a while to walk barefoot on the snow for 10 seconds, 15 seconds in the morning. There's a sudden boost of energy that I get off it.

You're a true survivor, man.

Thank you. And thank you for giving me this opportunity to come and talk. I'll send you some new stuff. There's one called "Talking To Me." I’m talking to me, talking to me. It's basically a song where I’m talking to myself. And the lyrics are:

You get respect if you die for what you believe in.

Fear no death as it’s ancestors uniting.

Never stop giving ‘cause it’s part of this life you’re living.

So it's just like talking to yourself and advising yourself.

Beautiful. I can’t wait to hear it. And I look forward to seeing you in person before too long.

Peace and love.

Related Audio Programs