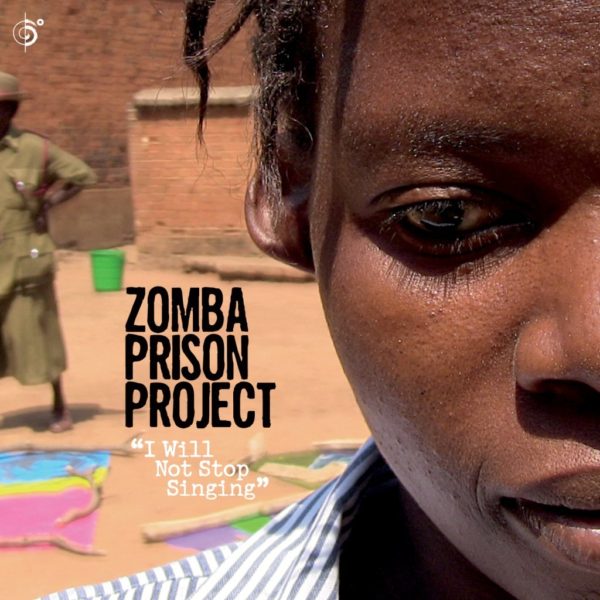

Ian Brennan is a globetrotting, Grammy-winning producer whose set of recordings, the Zomba Prison Project first put his work on our radar. That work established Brennan as a fearless producer who, along with his wife, filmmaker/photographer Marilena Umuhoza Delli, takes on projects that put marginalized communities at the forefront. Their latest project is a set of recordings made in northern Ghana among women who have been isolated from society as “witches.” Hip Deep scholar Mark LeVine reached Brennan by phone to talk about the new album, Witch Camp: I've Forgotten Now Who I Used to Be. Here’s their conversation, with photos by Marilena Umuhoza Delli.

Mark LeVine: Please start by telling us about yourself, and how you got—first to record with Tinariwen (who won the World Music Grammy in 2012 for the album Tassili) and then—at the other end of the Sahel some 1,000 kilometers to the south, in northern Ghana recording these amazing women.

Ian Brennan: Well, my background is steeped in music, personally. I don't remember ever wanting to do anything but play music and write. I grew up in Bay Area, outside of Oakland where I was born. Music became an unhealthy obsession by the time I was a teenager.

The guitar was your fetish...

I definitely had a very addiction-like relationship to music for most of my adolescence and young adulthood, until I was forced to start working to support myself at age 20. The only job I could get was for minimum-wage working as an unlicensed counselor in locked psychiatric facilities. That ended up being an accidental preparation for dealing with musicians the world over.

Myself and my wife, Italian-Rwandan filmmaker/photographer/author, Marilena Umuhoza Delli— who does all of the photos and videos for our projects— have devoted ourselves for the over a decade to trying to provide a platform internationally for original music from under-represented or in some cases essentially non-represented regions and languages. Since 2010, we have produced more than 30 international albums from across four continents: including Malawi, Rwanda, Ukerewe Island, Romania, Cambodia, and the newest nation in the world, South Sudan. We often prefer to work with those who have no previous musical experience and providing opportunities for hearing from historically persecuted populations such as those with albinism in Tanzania or the prisoners of Malawi’s maximum security Zomba Prison.

For me, ultimately, it's all about the music. On occasion, some people have mistakenly thought that these records are more about the story, but from our perspective the songs and voices have to come first and stand on their own. For this very reason, we’ve recorded more records that we haven't released than those that we actually have released.

I especially enjoy the projects with “non-musicians.” In fact, working with those individuals is my preference. When that method succeeds, the results can be stunning. But the projects would fail if the music itself wasn't something special, above and apart from the back story. For me, with art it is not about whether something is good or bad, but rather whether it's unique. Indeed, I tend to like weird or even “bad” stuff. My favorite records of all time, the vast majority of people would probably hate them— things like Vic Chesnutt, Ornette Coleman, et al.— and it took me a long time to accept that often the records or films I love most, the majority often finds awful or even repulsive.

Often when I produce for artists in the U.S. or Europe, I tell them that you might be able to produce a better record without me if you're trying to produce anything even remotely commercial. With Tinariwen, they were underdogs and we unexpectedly won a Grammy in 2012. But as happens, since then, Tinariwen has been assimilated by the very establishment that they were previously up against. In the newly renamed “Global Music” category, the pop star Burna Boy just won. The win is a great thing for Nigeria, but it remains relevant that he is signed to the largest of the world's three remaining record conglomerates. Between those three behemoth corporations, they control over 75 percent of the music distributed on earth. Regardless of how good or bad someone like Burna Boy’s music is, I was walking down the Sunset Strip in L.A. a year ago and looked up and there was a three-story high billboard of Burna Boy’s face and name. How can anyone from the margins compete against that?

What drew you to the witch camps in particular, given all the other work you've done in Africa?

Well, witchcraft accusations are, of course, not unique to Ghana. The phenomenon exists not only across Africa but in many other countries. Saudi Arabia, for example, beheaded a woman accused as a witch in 2011. Ghana is a great nation. As in most places in the world, the majority of evil actions are the work of just a few extremists that do not represent the majority. Our goal here isn't to vilify Ghana as a country. But what's unique in this case is that Ghana remains the only nation with official witch camps.

The increase in witchcraft allegations can be tracked globally to whenever there's economic growth, meaning that when an economy becomes more capitalist, when land is privatized and becomes more valuable, when foreign investors move in searching for oil or other minerals. In this situation, it is often older women who tend to be the most outspoken and often they've inherited their husband's land or house, so they are frequently accused of witchcraft as a ruse to evict them and seize their property. Often the accusations begin after something bad has befallen a village or one of its inhabitants. Someone, even a family member, will claim that the women is a witch. The accused might then make a forced confession while being assaulted to be spared death. Tragically, a 90-year old woman was beaten to death and set afire last summer in front of a crowd of onlookers in this way.

It's not just purely economic motives that lead to these accusations. Often the older women might have some mental illness or even dementia or physical disability like blindness or partial paralysis. Lest we cast stones at glass houses, how different is this really from the way we warehouse and institutionalize the elderly in America, especially those who suffer mental illness or have Alzheimers? And we know how catastrophic were the tragic consequences for much of that population throughout our current pandemic.

One issue in Ghana is that, when surveyed, a lot of people with influence admit that they still believe in witchcraft – doctors, lawyers, judges, police, politicians, etc. It's not just rural people who sometimes retain these beliefs. There is a universal tendency to scapegoat. If something goes wrong anywhere in the world most people reflexively want to find someone to blame. But it is a myth that witch-hunting is an ancient African practice. It was a colonialist import with roots that stretch back to Puritanism in England and America hundreds of years before.

Yes, the political scientist Shelagh Roxburg explains that “witchcraft is, above all else, a marginalized reality,” which seems to fit well with the setting you've laid out. Can you explain a bit more about how the camps themselves fit into this?

There were six official camps. Two have closed in recent years—one just before we visited, the other last year. But the situation is very complex, because the accused witches really have nowhere else to go. Some of the camps are run by various Christian denominations – some of the same groups who have encouraged such accusations, ironically. Some of the informal camps are secret (while others are often a fairly open secret). In some cases, the situation could certainly be thought of as exploitative given that the women have to work, usually chopping wood, tending fields or even being forced into prostitution. But at the same time some of the chiefs seem quite sincere in their desire to protect these women who have no one else to shelter them. Most of the women have been threatened with death if they return to their villages.

In Ghana there is a north-south divide just like in so many other countries – the U.S., Italy, North and South Korea, etc. Here it's the case that the north is historically much more rural and impoverished, and also predominantly Muslim. The country is large and the north quite remote from the coast – it can be a 10-hour drive from the capital to Tamale and some of the northern areas of the country can take another seven hours or more to reach from there. Indeed, while we were recording some locals we knew came up from Accra for the first time, and they were bemused and even condescending at times to their countrymen there.

Another aspect is that most of the women speak – and sing – in local dialects; they're not bilingual. They speak whatever the language was spoken in their village, so it's hard for them to even communicate between each other if they're not from the same area. There is in fact lots of isolation in many of the witch camps— with visible depression among many of the residents, most of whom are aged, if not elderly women.

Marilena [Umuhoza Delli] explained in one interview that what drew her to this project was that “my mother is from Rwanda and she's disabled, widowed, a three-time genocide survivor... Our objective is to provide a platform for these women who are otherwise censored or unheard.” In that regard, how are people at this early stage of the release responding to the music – its sound, affective power, evocative backstory – as you'd hoped they would?

What has the response been to the album so far?

The response has been quite passionate and positive. Certainly, these women’s voices and stories deserve to be heard. They possess so much more power and poignancy than an army of pop star puff or celebrity nonsense that dominates the media.

Speaking of the difficulties of communication, tell us about the process of the recording and the broader project.

We recorded in three camps, and all of the individual singers have remained anonymous at their request. One was an official camp, one clandestine and extremely remote, and the third an open secret. We went to Ghana not knowing a soul, not knowing what and who we would find. We learned of the witch camps almost a decade ago, but like many projects it took years to realize. A lot of the villages are hidden and sometimes it would take hours of vetting with numerous people before we were allowed to record. At first residents might deny that there was a witch camp, then later they might reveal, “O.K., maybe you're in the right place, but maybe you should talk to the that guy over there first,” and then we'd meet another person nearby and then another and only if we built trust would we meet the sub-chief, and then from there a meeting with the actual chief might be arranged.

For me and Marilena, we're often searching for people who don't consider themselves musicians. We ask them to tell their stories through singing, with no pressure whatsoever. It's much better to have a great 30-second song than a three, four or five minute mediocre tune.

Yes, most of the songs on the album are quite short, but their power and strangeness – in a good sense – more than makes up for their brevity.

Some of the songs are born out of hymns and traditional folk singing. But the majority of the songs were really just instant compositions made up at the moment. It's pure expression by an individual. One of the things we've encountered a lot, traveling thousands of miles around the globe, is arriving somewhere new and finding people that play and/or sing just like in U.S. or Europe. It's not surprising that in the kind of projects we do that if we have one trained musician taking part, even if they’re amazing, often they’ll wind up on the cutting-room floor. It's not a vindictive decision or one made in advance; it's just that these kinds of performers aren't usually as interesting, nuanced or compelling. The same thing happened with the Zomba Prison Project and Tanzania Albinism Collective, where the songs by the “professional” guitarists or singers weren't as compelling as those of the prisoners.

You know, getting to the point as a musician when you learn to unlearn everything you’ve mastered is the supreme task: How do you get back to being a novice? But of course in the case of instant compositions, they are impossible to repeat. But there lies there power— the urgency, tension, texture, and intimacy of a specific time and place. And that’s what is missing from so much contemporary music. It is overworked and made in utter isolation using identical tools regardless of location.

In the case of Witch Camp (Ghana), the women are playing mostly found instruments – tin cans, corn husks, firewood, tea pots. They’re using the stored harmonic energy of whatever is available in the environment. The kind of “instant compositions” that they’ve created have the power to move you even if you don't understand the language. In fact, even Ghanaians who knew the languages and dialects in which the songs were recorded told us they had a lot of trouble deciphering many of the lyrics. Perhaps some of that is because the women are quite old. Some are also shy, and they have never sung solo before.

The last person and the last song we recorded ended up being the last song on the album, too. There was one woman who was hanging around on the margins, standing and watching us most of the day very intensely and at the end of the day we were losing light and the chief's men were pushing us to leave, but despite their objections we went up to her and asked if she wanted to sing. She was clearly pregnant with emotion. What you hear in her song “Left to Live Like an Animal,” was the first and only take. Sometimes there is a moment in a project where you realize that you have an album— that beyond the beauty of the direct relationship with the artists, there is something of such profound emotional value that it has to be shared with the world. This was that moment, where the leap of faith was rewarded beyond our wildest expectations.

Despite being spontaneously created, the instruments and voices, and the various rhythms and melodies, did seem to come together quickly. How were they able to do that so well in a spontaneous manner? It seemed they were at least familiar with each other?

First thought, best thought. The only advice I ever give to musicians is to play “badly,” as horrible as possible.

Let's talk about the songs themselves. How many dialects are there in all? Even the titles themselves form a conversation of sorts on the album sleeve. How did you agree to titles of spontaneously created songs?

The songs are mostly mantras— almost prayers, saying the same words or phrases over and over again. And the titles tell entire stories all by themselves.

Some songs, like “Protection,” are more like chants that seem to be meant to be communal. Do you have any sense of how they were able to be spontaneously created yet seem as if they were well known.

That’s the magic of instant composition— when it works, it is palpable. That moment where things suddenly congeal, there is a suspended moment of freedom that transcends differences and intellect.

“We Are No Different Than You” is an especially relevant song, and the simplicity of the music and repetition pushes that harder. Do you see this album as helping convince other Ghanaians – the majority of whom still believe in witchcraft, or at least don't challenge it?

Our hope is just to do whatever tiny part we can to raise awareness. Education and exposure are the antidotes to most dysfunctional behavior. People will often listen to information in song or film that they would never entertain otherwise.

The song “Love” has such energy. Can you go into a bit of the production – where, how the chants in the background and the percussion all came together for it to work?

Usually, there is a warming-up and a build. The beautiful thing in this case was that a blind elder woman stood up unexpectedly and just completely took command. And what a voice she has.

“Left to Live Like an Animal” was the last track we recorded, on the last day, at the last camp, and it ended up being the last song on the album. While we recorded, a 70-year-old woman was hanging around the margins, but not participating. She was clearly pregnant with emotion and seemed on the verge of tears. When we attempted to ask her if she would like to sing, the camp authorities obstructed us, saying, “You don’t need to ask her. She can’t sing.” The camp authorities were pressuring us to leave the camp as it was the end of the day. But we approached her anyway and she said, “Yes, I want to sing.” She stepped up to the mic and made up the song on the spot, all under the disapproving eyes of the camp authorities. The song was one take, as that was all we had. And it is one of the most direct, raw, and honest vocal performances I have ever heard. In a different camp, on “Only God Can Save Me,” the woman said that “my song is my tears,” and she stood up the to the mic and wept. And when she was done, she bowed and stepped away.

Thanks, Ian. It’s an amazing piece of work. Any closing thoughts?

It is not by chance that the impoverished, elderly and disabled are the ones targeted. This fate does not befall people of stature. It is critical to remember that mentally ill and physically disabled hospitalized patients were the first to be exterminated by the Nazis, who deemed them to possess “life unworthy of life.” This process escalated to claim over 2.7 million people in extermination camps. That the term “witch hunt” has been co-opted and used so promiscuously by wealthy white male politicians throughout the neo-liberal rise in the West, only makes the misuse of the term by the privileged all the more abhorrent.

Related Audio Programs

Related Articles