It’s been awhile since I posted a column. 2022 started out with twists and turns, including a month-long gig in French Polynesia, a bit outside my Afropop wheelhouse, but a rich journey of discovery just the same. I return to a rising tide of music releases and live concerts reminiscent of pre-COVID days. So, time to get busy! I’ll start with a look at new moves in roots music from Mali, a bedrock destination for this musician/writer, and a country whose musicians never fail to surprise and delight, despite successive hardships and challenges.

In this age of Afrobeats, amapiano, African hip-hop and dancehall, African artists whose work is based in indigenous traditions and older genres face a challenge: how to remain relevant in a music market that can seem to be passing them by. Mali has long been a champion of what we loosely call “roots music.” The country is producing its share of young creators in current genres, but its artists’ fidelity to heritage remains dominant, weathering shifts in popular taste, political circumstance and global turmoil. Just the same, artists committed to cultural continuity do need to innovate to remain relevant, and no surprise, they are finding ways to do so.

Rokia Koné and Jacknife Lee: Bamanan

Top of the list at the moment is singer/songwriter Rokia Koné. She gained international attention as a contributor to the genre-bending Les Amazones d’Afrique project in recent years. Now she steps into the limelight in creative partnership with Irish producer Jacknife Lee, best known for his work with U2, Taylor Swift, REM and even Neil Diamond. The resulting album, Bamanan, projects a unique, modern sheen, less experimental and more tied to familiar Malian styles than Les Amazones, but nevertheless a bold departure from established formulas. And it’s getting noticed. Amid the ongoing stream of Mali music releases, this one earned a critic’s pick from the New York Times’ Jon Pareles.

The album opens with “Bi Ye Tulonba Ye,” which uses the metaphor of a party for the very idea of persisting with joy across boundaries of global culture clash. Lee favors ambient digital washes that bathe tracks in a warm, watery hue, while never obscuring Koné’s robust, razor-sharp vocal. Here, a rhythm track emerges only halfway through, with a steady beat and a cyclic, loping bass line.

Koné is a griot, although the underlying aesthetic of this album hews closer to the melodies and rhythms of Wassoulou music than standard Mande griot pop. And her vocal timbre is closer to Mamani Keita or Nahawa Doumbia than to griot stars Ami Koita or Kandia Kouyaté. Koné references history, as a griot must —particularly the 19th century Bambara Empire—but with an air of critique as well as veneration.

Feminist themes abound. “Dunden” weaves a gentle, polyrhythmic groove around a classic Bambara guitar riff, again highlighting the travails of a married woman. “Mayougouba” kicks out a straightforward disco club beat as it tells Malian women, “You’re perfect as you are.” The driving beat of “Kurunba” with its catchy hook and techno propulsion delivers a pointed response to a husband who rejects his wife after she’s granted him children: “I’ve got no more to say to you.”

“Bambougou N'tji” starts with a restless loop, a hint of electric guitar gracing its techno pump and drone. The song bears no obvious resemblance to the griot classic of the same name, and its message is also different, a celebration of old customs, including drinking at the bar after prayers and killing goats and chickens.

The emotional center of the album is a reinterpretation of an ancestral griot song, “N’yanyan.” Koné channels mounting passion, tapping the rasp in her fine, fluid voice backed only by Lee’s spare electric piano. She reflects on the fleeting impermanence of human life with evident poignancy, as the track was recorded on the night of yet another coup in Bamako in 2020.

For all the innovations on this album, Koné sings only in Bambara. In music, she’s wide open, but when it comes to language and message, there is no compromise.

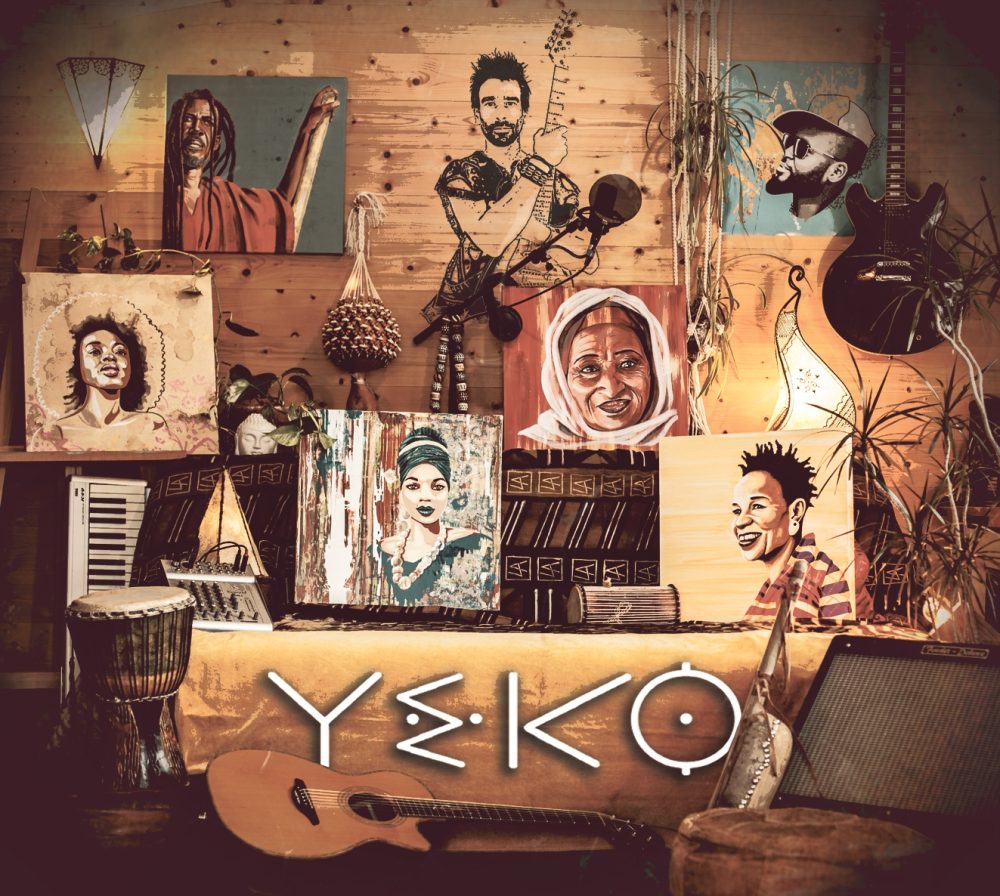

Yohann Le Ferrand: Yeko

Collaboration, such as Koné’s with Lee, is a fruitful, if risky, way to keep the music relevant. That approach pays off well on the EP Yeko, produced by French guitarist Yohann Le Ferrand, who has spent years performing and recording with West African singers. Yeko means “a way of seeing,” and on these six, beautifully crafted tracks, Le Ferrand joins forces with six artists. The set opens with a dense rocker, “Yerna Fassè” featuring the late Khaïra Arby of Timbuktu. A wheedling njarka fiddle emerges from a blasting din of electric guitars, but nothing can overshadow Arby’s august vocal.

“Doussoubaya” is a funky romp with a distinct ‘70s vibe, brought squarely into the present thanks to leading Malian rapper Mylmo. Mamani Keita takes center stage on “Konya,” with her soaring voice slicing into a tumbling 6/8 groove punctuated by handclaps and knife-edged soku fiddle breaks.

There are also quieter moments, such as “Sauver,” in which Malian reggae innovator Koko Dembélé glides from spoken word into song over soft acoustic guitar and ngoni. “Dunia” is a gorgeous ballad featuring Salivate Traoré, yet another Malian songbird.

The set closes with a cranker, “Yellema.” Vocalist Kandy Guira holds forth on a track that echoes the fierce momentum of Bambara pop legend Zani Diabaté’s best work. The rhythm section slays on this one, and Le Ferrand’s propulsive, cycling guitar riffs leave no doubt that he’s learned from masters, and well.

Fatoumata Diawara: Maliba

Innovation can be a matter of form as well as content. That’s the approach Fatoumata Diawara takes on her seven-track offering Maliba. This is not a standard album as such, but rather a digital-only release for Google Arts & Culture. The theme is the famed Timbuktu manuscripts, which clearly mean everything to Diawara, not only for their remarkable saga of survival in the face of brutal Islamist attacks in the north of Mali in the past decade, but also for the ageless knowledge and wisdom they contain—a gift to future generations.

In these songs, heard here, Diawara mostly explores the soft, introspective side of her art, with tasteful string arrangements on two tracks. The mixes are warm and spare, suiting the message—a plea to preserve and learn from history and culture. She begins with the gentle “An Ka Bèn” (Let’s Unite) and develops the theme with songs promoting education of children (“Kalan”), national pride (“Mali Ba: The Great Mali”), and hope for deeper understanding of the manuscripts (“One Day”).

The soundscapes here are appropriately reflective. Diawara, an excellent, self-taught guitarist, juxtaposes damped, staccato guitar lines with bowed strings, acoustic guitar vamps, and on “Save It,” kamele ngoni harp from her native Wassoulou region. For the final track, “Yankadi” (We Feel Good Here), her ensemble cuts loose with a celebratory groove and a spiritual message notably unconnected with Islam: “Djinns, protectors of Mali, I bow before you.” A video featuring dancers and Malian landscapes concludes the journey.

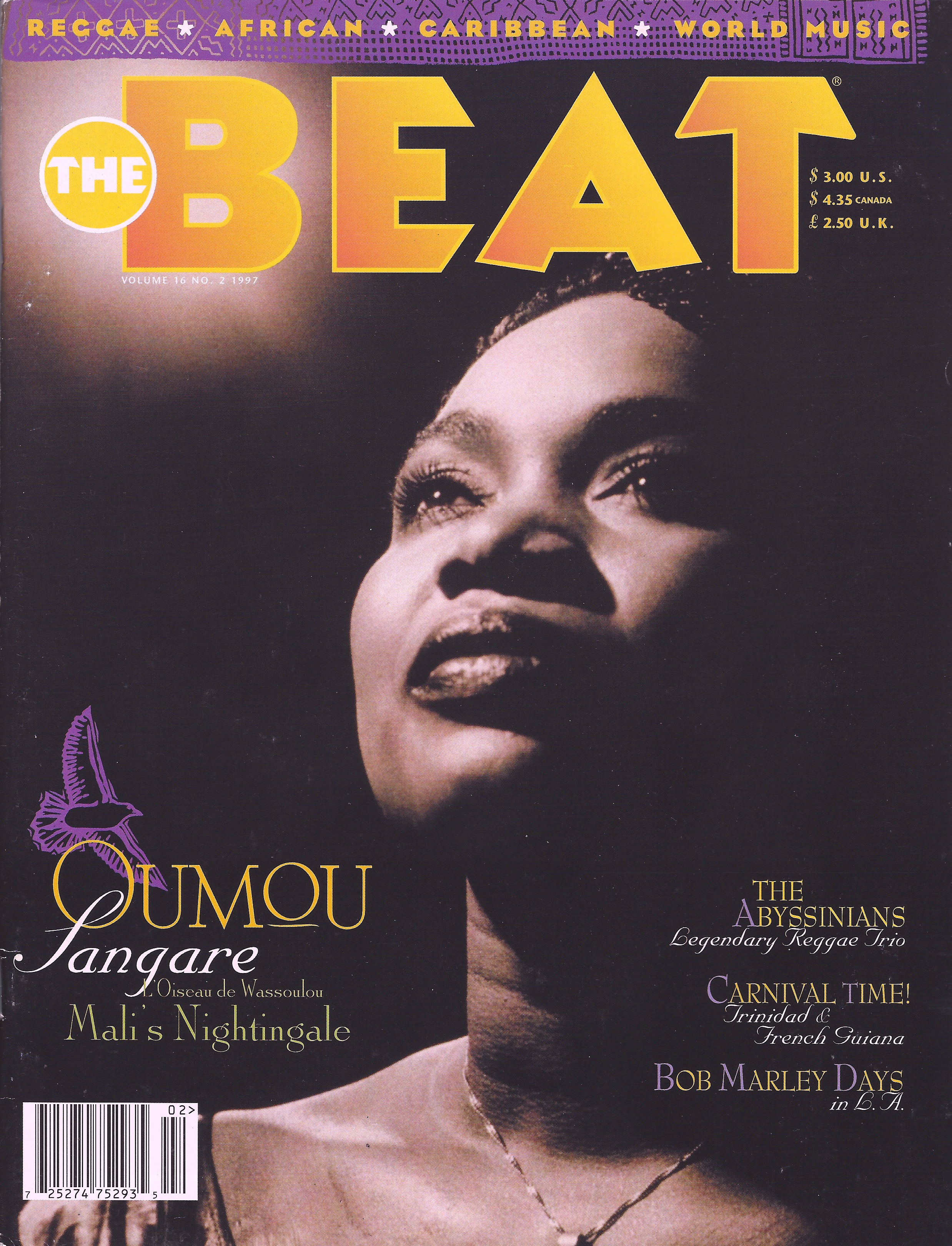

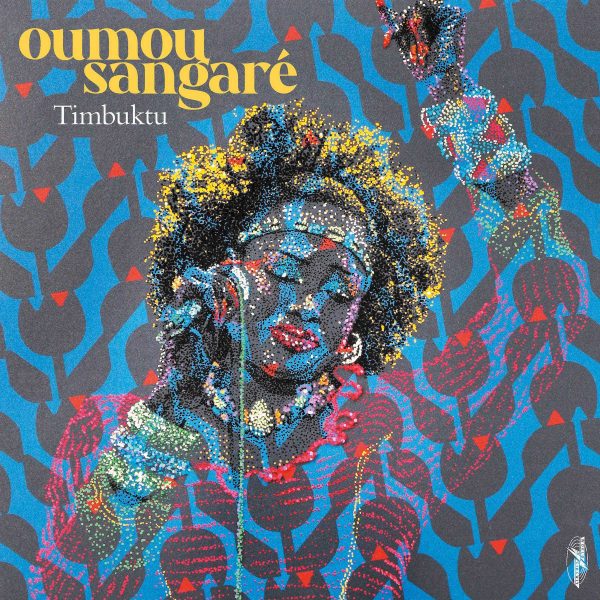

Oumou Sangaré: Timbuktu

Speaking of Timbuktu, that’s the title of the upcoming (April 29, 2022) album from the queen of Wassoulou music, Oumou Sangaré. We’ll have more to say about this release, including an interview with the woman herself. But there’s a sign here too that Sangaré is finding new expressive modes. The advance video, “Wassulu Don,” already featured on this site, has an electric, John Lee Hooker feel about it, not exactly futuristic, but a new direction for Sangaré. Of course, when you have one of the most iconic voices in African pop, as Sangaré does, moving with the times can justifiably take a back seat.

Related Audio Programs