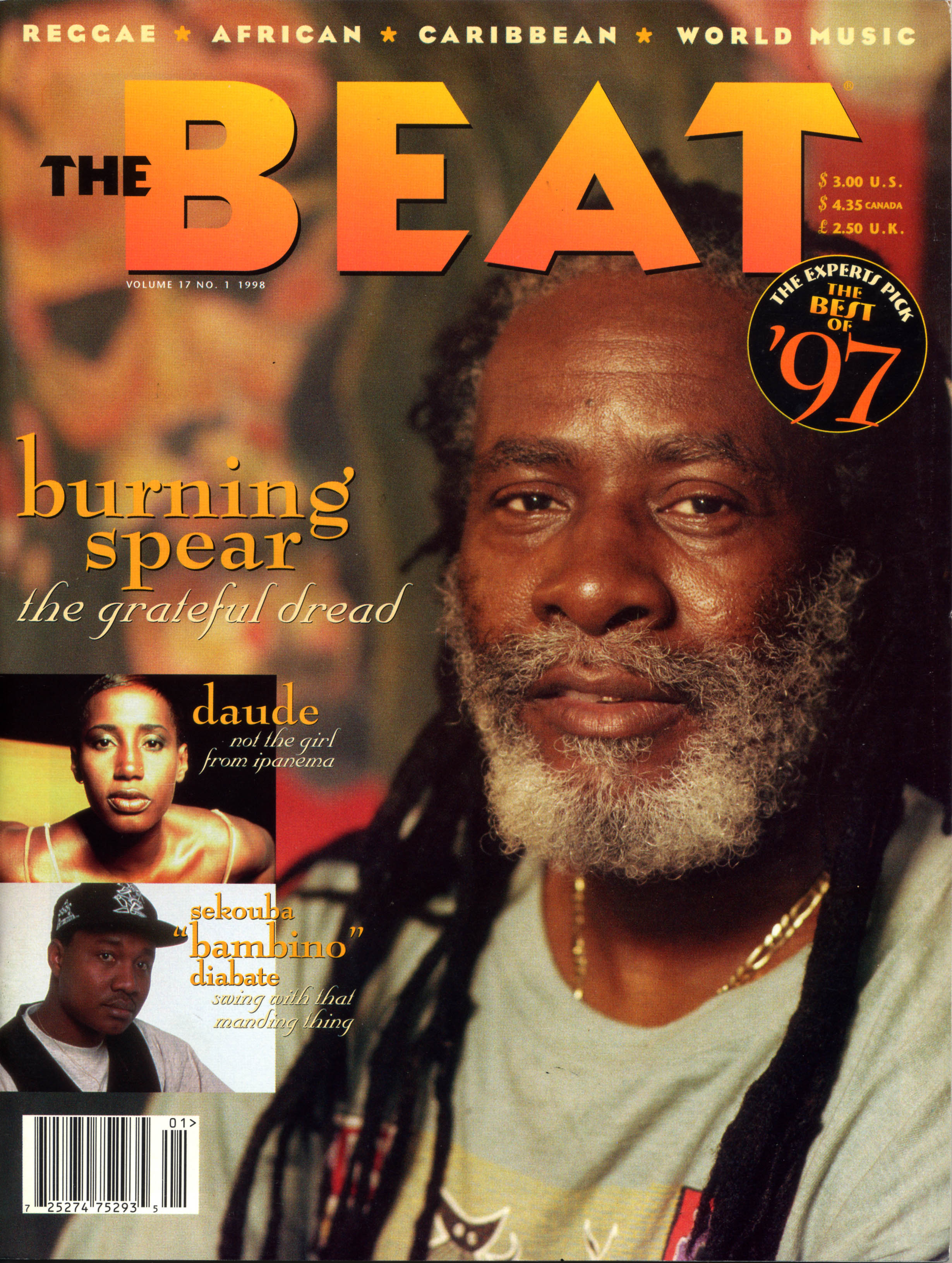

Considered not only one of the great voices of Guinea, but by many as one of the greatest living singers anywhere, we were quite honored to have a chance to sit down with Sekouba “Bambino” Diabaté before his packed outdoor concert at Festival International Nuits d'Afrique in Montreal last month.

Born into one of the royal families of griots, the Diabatés of Kéla--who have spread across Guinea and Mali for over 70 generations--Diabaté had music and a desire to be a spokesperson for his people coded into his DNA. Marlama Samoura, Diabaté's mother, also a popular singer in her time, died when Diabaté was only 3 years old. His father, who was a chief of the Diabaté family, played kora, but not professionally. Instead, he ran a transport business. When his son showed an interest as a young boy in wanting to follow his mother's footsteps, he says his father feared for his soul.

“My father was a griot,” Diabaté explains through an interpreter, “but he never practiced as one. So he was afraid for me because I was the only son of my mother and because 'a life of a musician is always about girls and drugs and everything like that,' he said to me. So he wanted me to have a regular life, and not to do music. He was afraid I wouldn't become a good person if I became a musician. So I had to do it in a good way because I was afraid he would disown me.

“My father was later very proud of me that I stayed a good person,” he smiles widely, “even though I was a musician.”

Diabaté took the stage professionally at the age of 15, in 1979, singing with the Revolution Band, one of the many government-sponsored groups under the dictator Sekou Touré, who ruled the country for 24 years. After hearing the young Diabaté sing, Touré wanted the boy to replace lead singer Aboubacar Demba Camara, who had died in 1973, in the Bembeya Jazz National Band. However, it took some time for Diabaté to join the group, supposedly because his village wanted to keep him for themselves and so many negotiations ensued. Eventually he did join them at 19. It was then he picked up the nickname “Bambino” (Italian for “little baby”) since there was already another Sekouba Diabaté in the band, famously nicknamed “Diamond Fingers” for his guitar virtuosity.

It was not long after he joined the group that President Touré died of a heart attack in 1984, and a military coup freed the country from his tyrannical rule. One of the benefits of the end of the Touré regime was that Bembeya Jazz National was now permitted to perform outside Africa.

“When we were allowed to tour in Europe,” Diabaté recalls, “it was a very good thing for us. It was the first time for me to see outside of Guinea. And soon we were going to Europe, Canada and the United States. Starting just with the airplane, which was a big experience for me. It all opened our minds to see the world and also let the world discover the music of Guinea. One of the things that I still remember most was our first outdoor festival in Paris. There were like 10,000 people. I never thought I would play before so many people. It was amazing. Also, after President Touré passed, we were able to go further into extending what our music could be... because music is made to evolve and change.

“Just the fact that I've had the opportunity to sing in different countries, to travel and all the experiences I've had have helped develop my voice. When I look at it now, and remember my beginnings, I realize there has been so much growth.”

Diabaté stayed with Bembeya until the band broke up in 1991. Since then, he has released nine solo albums, as well as collaborating on various recordings, including the Afro-salsa project Africando, which brought together New York Latino and African musicians.

“You see the rumba was always very present in West Africa,” Diabaté says, “so I actually grew up hearing that kind of music. The significance of the name Africando means 'Africa together,' –-all the different countries' music of the Africas were to be represented. There was a singer from Mali, others from Guinea, Burkina Faso, Benin, Senegal--and we all sang in our own languages. I sang in Malinké, of course.”

One of the ways to explore Diabaté's music is by checking out his videos, available on YouTube. While they lack slick production values, their somewhat home video quality makes them quite endearing. We asked Diabaté about them and he confirmed they are, for him, a bit like home videos.

“Yes,” he says, “you see a lot of my close friends, my family and fans. I love making them. So it's like that in my first videos, like 'Kassouma Ma.' It's specifically about the beauty of Malian women. My mother was from Mali and so it is a tribute to her because she wrote that song.”

(There is some dispute as to whether his mother actually wrote the song; however, she was known for singing it.)

In his video for the song “Taximan,” Diabaté gives us a bit of a tour of the city of Conakry, circa 2004.

“Now this song is about the difficulties of the taxi-driving job because there is lot of suffering,” Diabaté explains. “They see and hear a lot of things, but they can't express themselves. You know, like people are very aggressive with them. So they have to deal with these kinds of people. It's a song for taxi drivers not just in Guinea, but everywhere in the world.”

We also asked him what drove him to make his hauntingly beautiful cover of James Brown's classic “This is a Man's Man's, Man's World.”

“Oh, James Brown was my idol since I was a kid,” he says. “I used to listen to all his albums. So I decided to do one of his songs... and bring my African touch to it.”

When people hear the word “griot,” if they know it all, they typically think of it describing a musical or storytelling tradition. However, it is much more than that. It also falls upon the griot to help his people through music or storytelling. In Diabaté's case, he has used his music to make pleas for social change.

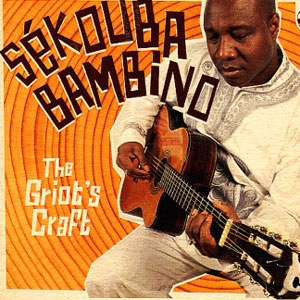

For instance, on his 2013 album The Griot's Craft, he wrote the song “Non à l'Excision,” which challenges the practice of female circumcision. In Guinea more than 200 million women and girls have undergone female genital mutilation (FGM). Every year, about 3 million girls under 15 are at risk of FGM. According to the nonprofit organization Population Services International, they credit Diabaté's song in helping both raise awareness and reduce the practice. In their 2016 study, they found the percentage of women who are aware of the adverse consequences of FGM increased to 59.3% in 2015, and the percentage of women who do not have an intention to circumcise a daughter of 4 to 12 years, also increased to 52.51% in 2016.

“Being a griot,” Diabaté says, “it's my role to be a messenger and to tell stories to educate the people. I'm also a father. I have daughters and other children. So I'm not only a griot for the people, but also for my family. So this issue of female circumcision is something I really think is bad and has to change. I saw it as my role to think about it, educate people and to transmit this message through spreading it in my music around the world.”

He has been an ambassador for the Red Cross in Guinea, and this year UNICEF appointed him their ambassador as well.

“It so happened,” he says, “that for about 20 years UNICEF was looking for an ambassador in Guinea. I believe it was because I was a well-respected artist and a griot who could help to communicate their messages that they chose me. I believe the way things will change is if we speak out about these issues. When I sang about female circumcision, it actually reduced the number of this happening in my country. So I can see how much impact I could have. This is why I want to speaking against these things. It does change the mentality. I wish it will end it completely.”

As part of his work with UNICEF, Diabaté is helping educate the country about child immunization, enforcement of laws for the protection of children, and a subject very dear to him, the lack of education opportunities for girls.

“It's a big problem back home in Africa,” he says, “The girls don't go to school. There are schools, but the parents want them to get married too quickly, and must then go to work in the market. We have to fight against this. So right now I am writing a song about this. It's not finished yet, but I'm working on it.”

Before we said goodbye, we talked about two more recent events in his life. The first, back in November 2015, while in Bamako, Mali for a concert, the hotel he was staying in was attacked by Islamist terrorists. Over 20 people were killed and there were over 170 hostages held during the siege.

“I was the first person who got out of the hotel,” he recalls. “The terrorists were in the hotel for three hours and we were trapped in our rooms. I had to find the courage to get out. They were in a room close to me and I could hear them talking. Then, when the army came, I heard them shooting and then they came knocking on our door. But people were too afraid to open their doors. So, like I said, I found the courage to open the door and left with the army. I thought if I believe in God and if I was supposed to die, then it would happen, but it wasn't. Thank God.”

We also extended our condolences over the loss of his friend, Kasse Mady Diabaté, in May of this year, at the age of 69. This Diabaté was considered one of the great singers of Mali.

“He was a griot,” Bambino sighs, “so he was born with a legacy and he left a legacy. So his children and all his family are playing music in that way. We grew up together. We have the same grandfather. My father was the chief of this family of griots, so we had a very long and close friendship. He was my big brother.”

Bambino’s concert at Nuits d’Afrique was spectacular. There was a legion of female fans swooning from the time he walked on stage through to the encore. It was a stunning set, which included some acoustic pieces he played solo on guitar.

For those of you around Silver Springs, Maryland, Diabaté will be performing as part of the Miss Guinea North America competition on Sept. 2. See his Facebook page for details.

Related Audio Programs