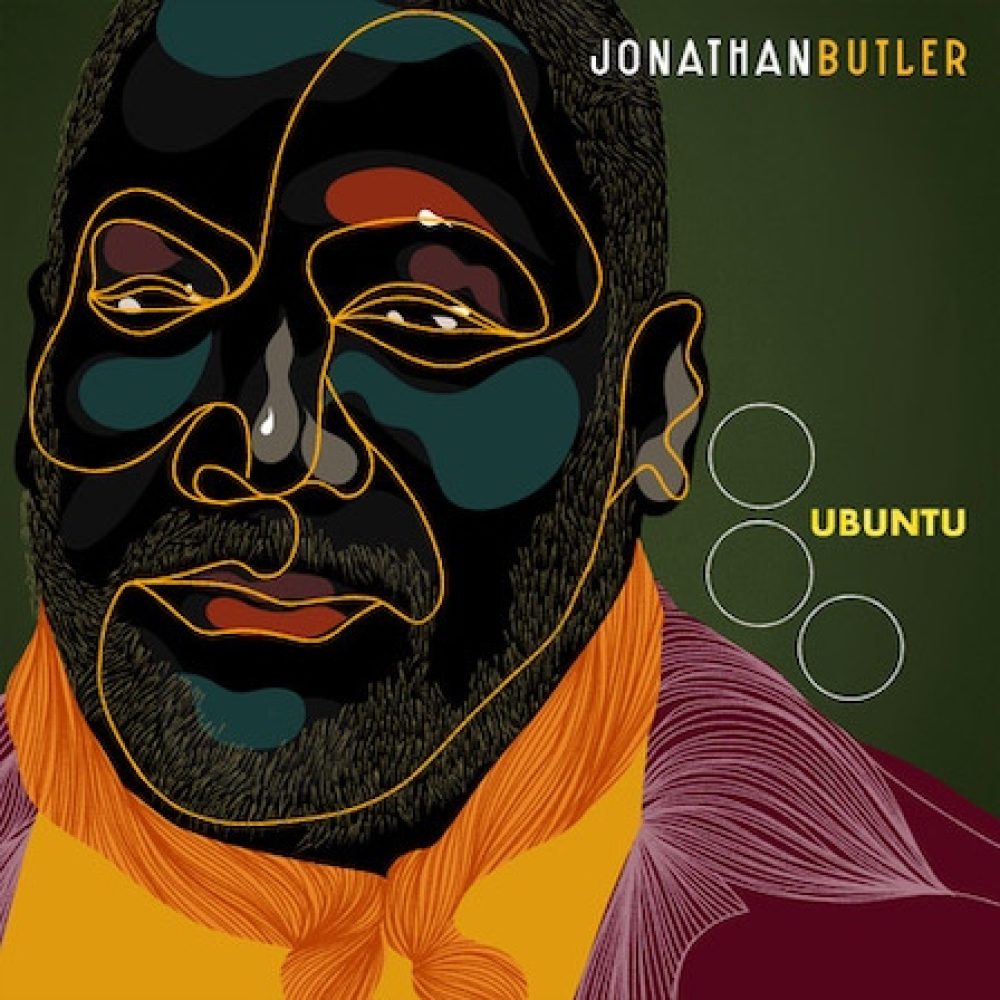

Ubuntu

“I am because you are.”

Ubuntu is the universal Bantu philosophy adopted by South Africa as a guiding principle after the abolition of apartheid.

Ubuntu encompasses the interdependence of humans on one another and the acknowledgment of one's responsibility to their fellow humans and the world around them.

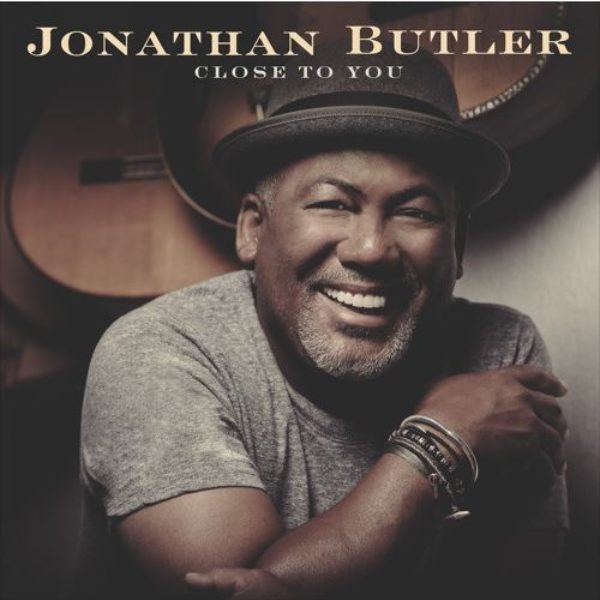

GRAMMY®-nominated singer-songwriter/guitarist Jonathan Butler drops a new album called Ubuntu after a five-year hiatus via Mack Avenue Records on April 28th. The title of the album might need some explanation. Butler was born in Athlone, Cape Town, in 1961, barely six months after the March 21, 1960, Sharpeville massacre. These were the darkest days of apartheid in South Africa when racist apartheid pass laws restricted every aspect of life for Black South Africans, who were forced to carry a passbook at all times. On this day police officers opened fire on 5,000 and 10,000 injuring thousands and killing 69 people who had peacefully converged on the local police station, offering themselves up for arrest for not carrying their passbooks. It was on March 26 that Nelson Mandela along with many others burned their passbooks openly in protest against the Sharpeville massacre where he and others were arrested after what was a treasonous action, resulting in what would be a 27-year prison sentence on Robben Island. Jonathan Butler was nearly two thousand km away in his own segregated Athlone which was designated a so-called colored area at this time, but this context affected the lives of every South African whether Black, white, colored, or Indian, the system would define the lives of everyone.

By 1994 with the pressure of sanctions and an armed struggle, apartheid was toppled, Nelson Mandela was released and a Truth and Reconciliation Commission led by Rev. Desmond Tutu tried to make peace with the past. It was at this time that Tutu suggested a way forward with forgiveness as the central tenet and the old Bantu philosophy of ubuntu was reinstated into the consciousness of the world. This is the background to the title of the new album by Jonathan Butler which draws inspiration from this Bantu philosophical principle.

In the past, he struggled with identity due to the complexities of living as a South African artist in politically driven exile as his music was being pigeonholed by the U.S. music industry, back and forth between r&b/jazz, smooth jazz, jazz fusion, and gospel. Since his early start singing for whites-only paying audiences in Athlone, Cape Town as a teen idol in 1975 with his first album I Love How You Love Me, he somehow held in the hope that one day he would be comfortable in his skin. With this new album, he has found his true voice by staying the course and sustaining a highly productive and successful career outside of South Africa, pumping out a mind-boggling 28 studio albums, live albums, and compilations for close to 50 years. He has wielded a subtle influence on upcoming musicians all over the world and was recently awarded a South African Legend award.

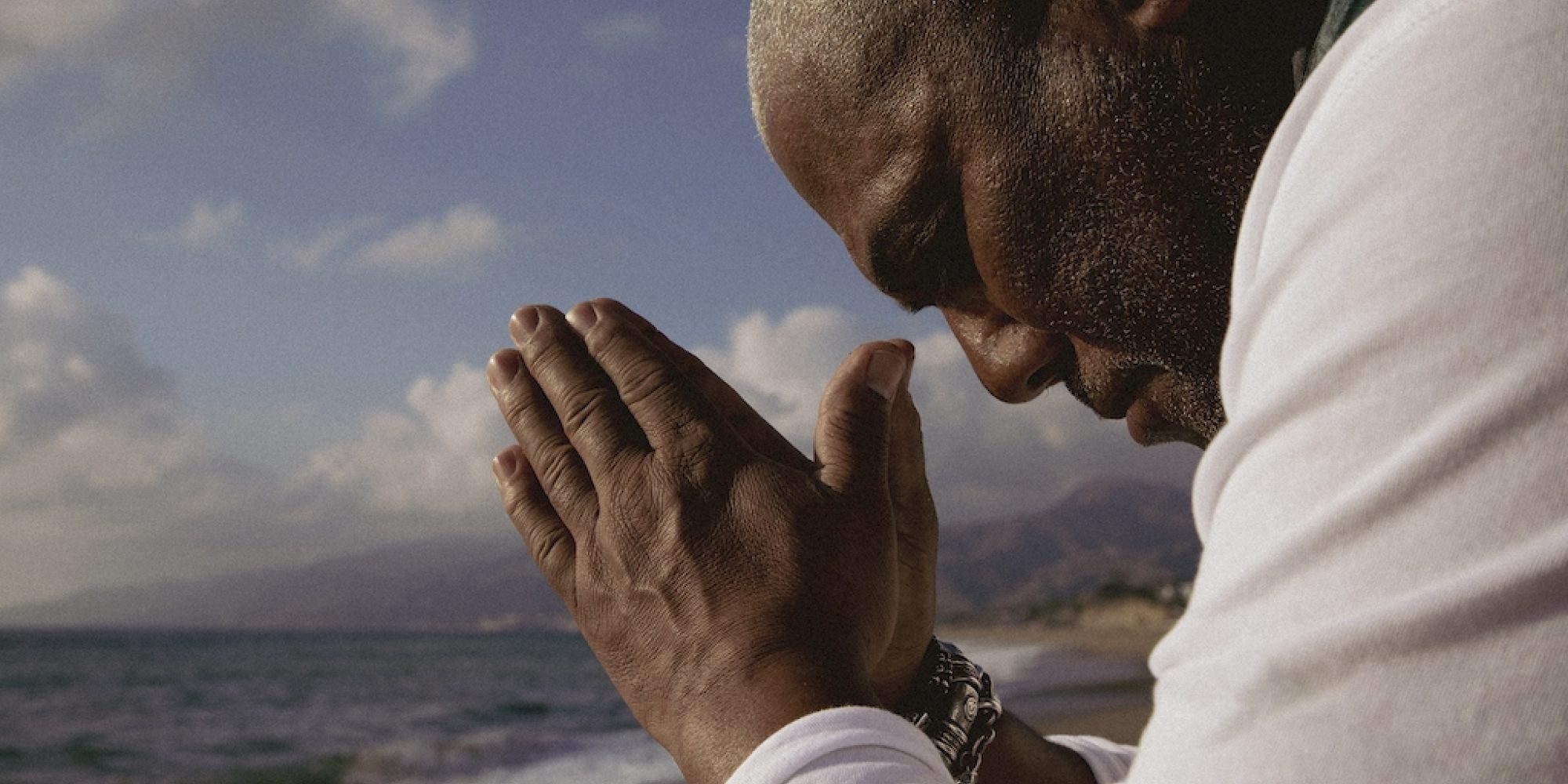

Today he stands as an authentic man finally comfortable in his skin and the years of work have paid off in what seems like an effortless collaboration with those he admires. His new studio album Ubuntu, recorded in a record-breaking three days was produced by the American musician, songwriter, and record producer Marcus Miller. Marcus is best known for his work as a bassist and resuscitated the careers of trumpeter Miles Davis, pianist Herbie Hancock, and singer Luther Vandross to name a few. Marcus has a gift for lush arrangements and bringing out the best in every musician he works with. I had to listen to the new album over a few weeks, going back and forth to each song, mulling over the subtle textures and echoes but here is my humble review of the album.

The album has local South African musicians opening with a unique interpretation of the classic Superwoman (Where were you when I needed you last winter), by Steveland Morris AKA Stevie Wonder. In a call and traditional response version assisted with the lyricism of South African gospel singer Ntogozo Mbambo, this cover is inflected with strings that does not diminish from the original classic. This opener confirms the deep respect that Stevie Wonder has for Jonathan Butler and his music, where the great maestro himself adds his signature harmonica solo to the track. Butler has been blessed in this way. Following this soul-stirring cover is the title track “Ubuntu,” and it will have you stepping into the progressive groove, where Miller´s musical toolkit is inspired with a South African twist.

The third track, “When Love Comes In” is a Mississippi Delta-inflected love song featuring blues singer Keb’Mo, an American revivalist and five-time Grammy Award winner who is also singer, guitarist and songwriter, living in Nashville, Tennessee. By track four we remain with what Jonathan has perfected over time which is a classic love song with “No Tomorrow,” where lush chords and progressions and his signature guitar phrases fit hand in glove with his vocal tenor. The next track, “Bon Appétit,” is an instrumental and a syncopation of echoes of Africa expanded with a scatting motif. This form of vocal improvisation is as old as the African continent itself, found in the trance singing of the San people of southern Africa. This form is adopted in recorded music most prominently in jazz music with the likes of Louis and Ella and adopted by many including George Benson. Jonathan has been employing this vocal technique for years by inflecting South African vocal tones and he has developed an African musical language all of his own.

The sixth track “Rainbow Nation” is an anthem, interpreting another term coined by Archbishop Desmond Tutu to describe post-apartheid South Africa after the country’s first fully democratic election in 1994, to inspire the continued healing of South Africa. What is great about this track is that Marcus Miller, outstanding bass player that he is, gets to play musical tag with Jonathan in this refreshingly beautiful melody with fragments of his native Cape Town Jazz fully apparent to the trained ear. Back to focusing on Jonathan’s guitar storytelling instrumental on the next track “Peace in Shelter,” co-written and performed with sophisticated composer and keyboardist Russell Ferrante of Yellow Jackets fame, is dense with an orchestral aesthetic reminiscent of Alhambra and Mozart and everything in-between. This is where Jonathan illustrates his capacity to embrace sounds from anywhere in the world and his work with the most innovative musicians in the business. Wrapping up the album, with the last four tracks he puts himself firmly back in Cape Town of his youth with “Coming Home,” “Springtime in Afrika," both with Marcus Miller sharing the melody. Jonathan has the ability to create in any genre and also takes us into the hypnosis that is the reggae ride of “Silver Rain,” destined to be the certified hit on the album. “Our Voices Matter,” the final track inspired by the Black Lives Matter movement brings us full circle back to the concept of Ubuntu, influenced by his own life events and the events following the public lynching of George Floyd, reconciling the world to respect the humanity of Black people ending the album on a note called hope. It is such irony that even with his enormous success, the ghosts of racial segregation and apartheid still haunt but here in the U.S., as he recently experienced a confrontation at the Goose & Gander restaurant in St. Helena, California.

I had the honor to sit down to speak to Jonathan Butler over Zoom about his unique spiritual and musical journey and return to his roots in South Africa with this album Ubuntu.

Mukwae Wabei Siyolwe: How are you?

Jonathan Butler: I’m excellent, excellent. Just recovering from a long trip back home from Cape Town.

Oh, shame. When did you get back?

I got back Thursday, the 23rd March. I was there from February 13th. So like, six weeks. So I just came straight home, straight to shows. But I'm good. Got a cup of coffee.

Oh, good. So home is also L.A.?

It's been L.A. For a very long time. A very long time.

Tell us more about that choice of the name Ubuntu for your new album and how you were motivated by that.

Over the years, the course of my life, my career, I had the privilege and the honor of spending quite some time with the great Archbishop Desmond Tutu. And much of what I have seen in him and much of what I've heard from him, and much of what he stood for and how universal he was in his thinking, and just in his manner as a person and the light that came from him was something that I was very attracted to and his teaching as well. And that's how Ubuntu came about. For me, it's it's sort of, you know, learning from this incredible light of a man and also the country that I was born in the sense of community in the face of all the hardship, and the stuff that we've all had to endure during apartheid and segregation. Ubuntu came because it was such a record that kind of embodied everything that I am today. And also, I wanted to send the message that I'm at home. I'm always at home in my music. Whether I live in Los Angeles, and whether I've been here for 40 years, I would say I've always been going home, and I've always been connected to South Africa.

And Ubuntu is that for me, knowing that I belong to a community. I belong to a village. I belong to a people, and that we draw strength from each other. We draw strength even in the toughest of times. I said it the other night in Carmel, Indiana. We can make a sad song happy and we can make a minor chord feel like a major chord, and that's kind of like my way of summing up “ubuntu” as well. I saw the village that stands together and everything just fell into place. Marcus Miller was on safari with me, him and his family. I took them to South Africa for the first time as they've never been on a safari. The kind that I do, which is more, as it embodies not just your commercial safari, but you get to know the people, you get to eat the food, listen to the music. And that's where it all started. The record started in Cape Town, and then we flew into Johannesburg, and by the time the safari ended, we started the record in Johannesburg.

It's been many years since I've actually been in Johannesburg at a recording studio, actually, since I was 12. That was the first and last time I was in Johannesburg recording. And then my greatest inspiration, Stevie Wonder, was so generous to say yes and bless the album with his own song. And a friend of mine, Ntogozo Mbambo: she's incredible. So Ntogozo said yes, and she came and sang on it. And it's all local musicians, everyone on the album is from home, and we're living in this kind of world where smooth jazz is a place where I landed without permission. It just kind of landed me there.

People called me "smooth jazz when I really felt more deeply that I was a world music artist and I represented Africa and that's ubuntu. I wanted to represent Africa in my music, and I wanted people to not be confused about it. That's why it’s Ubuntu, even though there's some kind of classic r&b stuff that Marcus Miller had written. But it's my springtime in Africa and there's some moments that I address the pandemic with "When Love Comes In." And also a song I wrote with Russell Ferrante. What was that? What was the tune called, the one with Russell Ferrante? It was “Peace and Shelter.” That's during the time at the height of the pandemic when things were absolutely just chaotic and deadly. And so I found myself writing those two songs, especially during that time. But I am because you are, is where this message comes from.

That's amazing. I mean, I would love to ask you, in terms of your own process, do you feel like you've responded to stuff before it even happened? In terms of your own connection with your music, do you get inspired before things happen that you’re just like, “you know what? I've got to write a song that is about ubuntu", or was it the COVID pandemic that forced you to write?

I think you're right. I don’t think anybody actually asked me a question that way before, because I remember when George Floyd was lynched in front of the world. I do remember immediately being so impacted that I wrote “Our Voices Matter” and for instance, that was an example of that. It's like, that's how I write. I think that's how I write. I mean, during the pandemic, I wrote a lot of music. I think I must have written four albums in the whole time that I was on lockdown. And each one kind of drew me closer to home. For some reason, I went back into finding Jonathan Butler. Where is he? Why has he been quiet for five years in Smooth Jazz? This is the first original album in five years. I'm surprised promoters still call me for touring repertoire from yesteryear and not so recent. But, yeah, it really comes from that. “Coming Home,” especially that's another song I wrote on safari. But the conversation before that was, say, “Marcus, I'm actually here in South Africa looking for me,” because before this album happened, I didn't feel like I had the right things to say. I just couldn't connect with my studio and my instruments. So what I would do in the morning, I would stand in front of my grand piano, and with my phone I would play little pieces of guitar music. And my wife said to me, “Why don't you call it, “Guitars in the Window?” So I called them “Guitars in the Window” and it became like a series of tunes that I would do every day or every other day. I would play a little bit of music. And so that kind of helped me a little bit, too, in lock down, to stay connected to stay connected to the instrument.

But I didn't really feel like I had found what I was really set for because I was kind of wrestling with smooth jazz. I hate to bring it up again, but I was kind of wrestling not wanting to be there, because there was just so much of the same thing. There was so much of the same. Like each day, there'll be a programmer who will program 93 beats per minute so all songs would be the same tempo. And I couldn't see myself in the middle of that. I couldn't see how I fit into that. And then slowly, it was about going through the process of listening to all my stuff that I was writing through lockdown. Ubuntu was like a groove that I loved. It was like a four bar groove that I just love to play on my laptop. And Marcus said, “Why don't we just finish the song?”. So he went so hard on it, and he brought out all the guns on the song, and I woke up and I said, “Yeah, this is it. It speaks to me”. And it's also, like, just being comfortable in my skin. That's really why this record is the image of my face, the way it is. It's just a symbol of someone who recognizes his roots, who he is, and has transitioned into being a world artist. But I guess throughout my career, I had to always roll the dice or take the risk, because if you don't, there's no reward. If you don't take a risk and see what's on the other side. I did a Burt Bacharach album. I did all the Burt Bacharach background music. I did it Afro style. I changed it up to like a South African flavor. It wasn't as well received as I would have hoped, but for me, when I play it live, there's such a response. So I don't know. Some artists translate better live than they do on CD and some better on CD than they do live, so there's that as well.

That's amazing. That's very interesting. So you would say, then, that the proximity kind of helped that artistic block, just being close to South Africa, just being on the land.

Yeah. And like I said, I'm 62 this year come October and I do feel like when I'm among my colleagues and musicians and artists there, I know and feel like there's been a little bit more seasoning sprinkled on me, you know, like a little bit more spice. So I'm kind of aware of that spice. I use it. I use it on stage. I use it in my conversations. When I was younger, I was always trying to find myself in American culture. That's the other thing. When you're an African and you come to America, you are always going to struggle a little bit with American culture. Even if you're Trevor Noah, you're going to struggle with American culture because, yes, you are respected as Trevor Noah, but you're not Chris Rock. You're not Dave Chappelle. You have to sort of come into your own. And that's why when I see Trevor at home, the first time I saw Trevor Noah at home, I was like, man, I get it. I get everything the same. The accent, the whole the Zuma thing, whatever he does, our president, I love it. And I found when I came here to the U.S., I had to kind of wrestle with the culture and how to continue to carve out my sound and my style that, thank God, became acceptable.

People loved it. People loved the stories. When I was younger, I wasn't so much into storytelling. I was just trying to make the music, just create the music, play the song. They knew it. But now I can stand on stage and actually talk through the song with people, tell them a little bit of history of why this song is what it is. Like 7th Avenue where I grew up in Cape Town or Crossroads. Where Crossroads was in Cape Town. I can talk to people on stage about it. So it took me many years to come to this place where I'm now comfortable. I'm now making the music and it feels good to make this kind of music. It's like, “Hey, this is you. This is who you are.” I tried the compromise thing. I tried a little bit of that and I've seen where I remember I was doing a song, I wrote a song called “Mandela Bay” on the Madiba album. It was a song for PE, for Port Elizabeth, because that name was going to be changed from PE, to Mandela Bay. And I asked Bra, the late Bra Hugh Masekela, to play on it. But the record company decided they wanted to change the group to fit the smooth jazz market. And that gave me such anger and it put me in a very angry state because you're going to give this song to some white producer in San Diego to change what the true essence of the song is? So I've had to go through all of these processes and, as you can tell, I'm trying to just move away and move into my own journey wherever it's taking me.

Wow, I'm so surprised about that. That record company had that kind of artistic license to be able to tell you who you can collaborate with.

It's a wrestling match now for me because I stand so strongly for this album Ubuntu and I think if you don't live in Africa, if you've never traveled through Africa, if you never had the food there or listened to the music there, you can't speak on it from the States and say, well, I think this will really go down great in Zambia or Uganda. I'm sort of hoping to steer his project so that everybody understands what it is.

Absolutely. I mean, just looking at what for some people, it might not be positive thing, but in my books, I'm seeing how the Nigerian music industry, they've got their own big label, Mavin Records, for example, who basically are Africans through and through the whole process. So there's never, "O.K., could you play this little piece?" I'm really happy for your emancipation, that you can, and you should, be able to do that at this point in your career. It's just like my music, but I'm sure you'll share more about that. Do you think that your entry into a bigger audience within the U.S. market was possibly to due to your faith, your Christian faith?

Well, that's part of the journey. That's part of my Jonathan Butler's story, because that sort of later in my career, it became more evident, and it's something that I had. Trust me, I prayed over this for a long time because I became a born-again Christian when I was 19, and prior to that, I was a huge drug addict. I went from the big, famous, young star, teeny bopper idol in South Africa, all over South Africa, to being caught in the net of the drug cartels in Cape Town, all over. I was probably, I could say maybe on a suicide mission at that point in time because I played with a lot of great bands. I was hanging around with Hugh Masekela, Mbeki Mseleku, Dennis Mpale, Duke Mukaze, the All Rounders... Oh, my God, Tsepo Hotseng, all these guys. I was hanging out with everybody. But this journey from all of that took me down a path where I became a born-again Christian. And the transformation of that was the start of another journey for me, because I wanted to stay away from jazz and stay away from secular music, and I wanted to pursue ministry, and that's what I wanted to do. But I soon began to feel that God, or the Universe, whatever you want to call it, that God began to pull me away from what I thought was the right thing, and I ended up back in the nightclubs. I ended up back in the secular world, and I realized it was cool because I was growing in my faith. I had a lot of help. I had a lot of mentors when I made that transition to becoming a Christian. So I have a lot of great men and women who mentored me all the way to where I am today. But this has been a prayer answered, because I recorded, wrote, “Falling in Love with Jesus.”

One of my favorite songs, by the way.

Thank you. Thank you. I had no idea. But I will tell you the truth, I used to say to God, I don't want to do this unless you release me to do this. I don't want to be just another r&b singer putting gospel songs on an album, which I did before I had maybe one or two songs on secular records. And it's crazy because when I look back on it, back in the days of Dorkay House and the All Rounders, I was drugged out writing gospel music. I was drugged out. I mean, I'll show you LP´s where I actually wrote gospel songs while I was high and recorded it. I have it on the vinyl covers. But the true transformation was when I was going through discipleship with these men and women pastors who mentored me. And when I wrote “Falling in Love with Jesus,” it's almost like a prayer. The prayer was answered because I had no idea the song was going to be this huge song all over the world. I guess churches and believers from all over began to open the door for me, open their doors for me to come in and not only just be a gospel singer in their church, but be a musician and take a solo and then sing the song and share my testimony. And God, just like little fires everywhere started happening. I heard my hero Stevie Wonder, sing it live on TV and he still sings it.

So it was really a dream that was fulfilled in my lifetime because I knew there was an anointing on my life to do what I do, but I just didn't want to do it for the sake of popularity or flirt with these important, powerful words that can be life changing. So I get it now. And I have a responsibility. I understand the responsibility that I have that it's on me. So on my shoulders to be this person that comes on stage and not only sings “Lies” or “Holding On,” but in the middle of the set, I have to play “Take Good Care of Me,” because if I don't, people will kill me. It's like people will just like, nah. Now it’s just amazing that when you take religion out of the whole conversation and see it as spiritual as a spiritual interpretation, then it's much better to understand. And there's more freedom that comes with that. There's liberty that comes with that.

That's a really good insight from my position. You know, being here listening to music from the diaspora and Black music from all over the world, all day, every day, every single genre possible, and every single genre that is to be born, what I'm seeing now and what I'm sort of sharing with other artists and encouraging them is to embrace all of who we are, because it's limitless. It has no beginning and end.

Right, right.

Inspiration is forever.

Exactly. Yeah.

So I'm really excited to see you do more music in many different genres and embrace all of who you are that we haven't seen yet.

Well, I was just at home, and I played in Maputo. I played in Botswana, and there was a Koi-San group, and they were amazing. So there was music that really gave me another boost of, like, yes, I’m changing. And that is what keeps me relevant. I want to say that, because I was fortunate to play with a lot of new, young musicians in South Africa. And I mean, it's almost like it was anti-climactic, almost the other day when I first when I landed back here in the U.S., and I went straight to Phoenix, Arizona, to play. And back home in South Africa, people sing all your songs. They'll give you back everything, what you give to them. So when I was playing in Arizona, I was like, oh, man, shoot. Do you only know you're only giving me back this much now, but back home, it's like, oh, man, it's everything. But I realized you have to command the stage. You have to be intent. You have to have intent when you go on stage, you have to have intention, and you have to channel your ancestors. And like the Bible says, you have to have on your breastplate like, a warrior. You have to come prepared to go to war, to battle, because you never know what kind of energy is in the room. And that happened when I was even younger, when I was growing up and singing six, seven years old in Durban, in white nightclubs, and you have to put on your armor and not demand but command people. Where was it? Sunday night was epic in Carmel, Indiana, because they were like an orchestra singing back to me. I was directing harmonies, and they all sang everything I ever wanted them to sing, even though they didn't know what they were singing, but they were engaged, you know. So there's a lot of great music from Africa, and I think Africa is going to be leading the world and it is where all this new great music is going to come from. Nigeria is one of them. Nigeria is definitely one of those countries that has great stuff is coming out . And I'm really focusing my energy on a lot of the young guitar players in Cape Town because, damn, they are insane. They're just amazing to listen to. They're amazing to listen to and also I’m getting an understanding that it's time for me to pass the hard drive. It's time for me to give the hard drive and download it into the younger minds and the younger musicians now. And instead of just trying to hold on to my hard drive with the information, I think it's time for me to download it.

That's interesting. But please don't stop.

(Laughter)

No, I won't stop at all. I'm too in love with it. I complain when I get home from a long flight. I always complain a little bit and get a little grumpy. But when the lights go on I'm the happiest guy. Yeah.

Of course. And just to that point, I mean, what we've been happy to sort of reveal at Afropop over 35 years is the fact that Black music globally is contemporary pop culture. We drive it. And so we're not hiding from that anymore. And we like to remind artists that you're not marginalized. You're the center and have been the center. It's just that the way that it's been reported has been like, you're on the margins, but you're actually in the center.

Actually, absolutely. Yeah.

Just lovely. I just recently sort of did an article on the roots of rock and roll went back to an African-American musician called George Johnson. Yes. But before him, I found out that he could be a great great great grandfather or relative of my own children. He was a musician in the 1890s at the Hopson Plantation and he recorded the first boogaloo song.

That's amazing.

I know. So he is, in essence the first in recorded music. But things like that. Information comes to us especially like you are saying when you're in tune and you have intention, and that all of those kinds of inspirations and information will just appear.

There's a song that I was watching on Netflix while I was in Cape Town. I was watching the song that is in The Lion King. A song which lots of white artists took credit for to this day. There was a guy who even said that he wrote the song, but the actual composer was from Soweto. Solomon Linda and The Evening Birds called Mbube who wrote and first performed the song back in South Africa the 1930´s and I was fascinated.

Solomon Linda & The Evening Birds, Mbube (1939)

The Tokens - The Lion Sleeps Tonight (Wimoweh)(1961)

Miriam Makeba - Mbube (Live, 1963)

Wimoweh - Karl Denver (1964)

Billy Eichner, Seth Rogen - The Lion Sleeps Tonight (From "The Lion King" (2019)

Like, it's so important to look for this information, to search after this information. Because a lot of our music has been copied and has been used. Like you said. My grandfather was from Monrovia, Liberia, and was a banjo player. Came through this Buffalo Soldiers era, through slave ships into Simonstown, and hence started the Carnival. Cape Carnival in Cape Town. We all came out of that whole carnival experience. You weren't a Butler if you didn't participate.

That is so fascinating. I didn't know that about you.

Yeah. And so I researched this. I was in tears when I learned all of this stuff through a very dear friend of my father's because he said to me, he said, “When are you leaving?

he says, “Where do you live?” I said, “In Los Angeles.” He goes, “But you're home, aren't you?” I said, “What do you mean?”. “Your grandfather came from the U.S. through Liberia through the slave ships and ended up in assignments down here in South Africa you know. And so it's like almost knowing. That's why I'm saying the music, the African essence and spirit of music is in me. And so when I was younger I was a crossover artist with Take Good Care of me and the double album.

Then I'm on Johnny Carson and Vh 1. And so it was unusual for a Black artist, especially from South Africa, to become a crossover artist in the U.S. So my identity was already shaken a little bit because I knew myself to play at 7th Avenue and other music from home. I grew up with that stuff, so it was like, oh, every week or every month on the Billboard Chart, I would see, oh my God, you're on the r&b chart. So it was like, if this is years and years and years and years of coming into transitioning into Jonathan Butler from South Africa, like I always said to my neighbor, I said in an interview in Joburg, last week. I said, “If my neighbor ever came and asked me where I was from, I wouldn't say I'm from the street where I just bought my house. I'm from Belgravia down the road from Athlone, Cape Town. That's where I'm from." And it's important to kind of have that conversation with yourself as well so that you always remember who you are, always remember what you've been through. The stage is like for us… it’s like a place where we can let out those painful experiences. Some people write about that. It’s a place where you can share that. We can release all that, be healed from it too, through music. Coming back to this time and all the other stuff that I've done during COVID will probably be released in years to come, but it is all amazing music. There's one song I wrote for the great Alan Kwela, who I used to love as a father figure when I was a little boy in Joburg in Hillbrow. Alan was always around and Alan was one of the most amazing jazz musicians I ever heard. Nobody there knows Alan, talks about Alan Kwela. But this was where jazz really came from in Johannesburg back in the day.

That's right. With Todd Matshikiza and Sophie Mcgina. I grew up with that crew in Zambia and England. Yeah. Had them as (artistic) mentors. Yeah. I never felt like an impostor because I always had them close, but it was hard because I understand your journey, where you have to be this person, but you're in a place that has nothing to do with that space that you're from. So it's always like, where do you find that inspiration? And I'm just so glad that you stayed so connected to your roots.

My wife is here. She knows from the food. Not just the music, but the food is where I'm so true to our food.

Yeah. And of course, we have so many proverbs and figures of speech related to food and the act of taste and eating. Eating.

We have lots of stories, and South Africans have a lot of stories. And if you give them a chance, they'll tell you their story and more.

Please keep telling your story.

Well, you know, I was deeply honored at home. I was presented with a Legends Award in Johannesburg a couple of weeks ago, and it's Music Week. I've been involved with them in Canada. I was one of the ambassadors that spoke on African music. And so they want me involved as an ambassador for the whole continent of Africa, you know, to be an ambassador. To speak on and to bring our music forth. So one of the things that I want the listeners to know wherever they are, is that I'd like to visit your country and plug my amp in and come and play for you. And I can tell you my stories, and you can tell me your stories, and I can come away. I remember when I was in the Ivory Coast, it was so amazing hearing Black people speak French. And so it inspired “Many Faces” on the album Surrender. And that's the whole thing about how we stand together. And before Heavenly Father comes to get me, I want to see Africa. I think I belong, and I feel a deep pull for greater things to come in Africa. For me, I believe that America has been really kind and good to me. But I think I wrote myself a note the other day, and it said, when a man gets on in years, he wants to spend it with his people. That's what I wrote down for myself as a little note that I'm going to keep. So one day I'll be able to go home, teach, elevate, inspire, encourage young people to be their best selves. Write their own songs and tell their own stories.

And own their own masters.

And own their own masters. Yes. Own their own masters. I've been in this situation for so many years that so many times I was told, why did you start your own record label? And I guess I'm still from the old school era where you get signed and you get a manager, you get an accountant, you get a lawyer, and then you go on stage and record. I still believe in getting a lawyer, and some of us need an accountant because we just don't know what to do with the money that we have. But, yeah, I think that's another conversation that we need to inspire them, and it's doable for them. Right now, they have a laptop, they have a keyboard. They can write their own music and put it on Spotify and put it on iTunes and own it.

Exactly. Well, it's such a pleasure to speak with you.

Likewise. Well, take it easy, nice to talk to you. Awesome.

All the best and love to your family.

Thank you. Thank you. Goodbye.