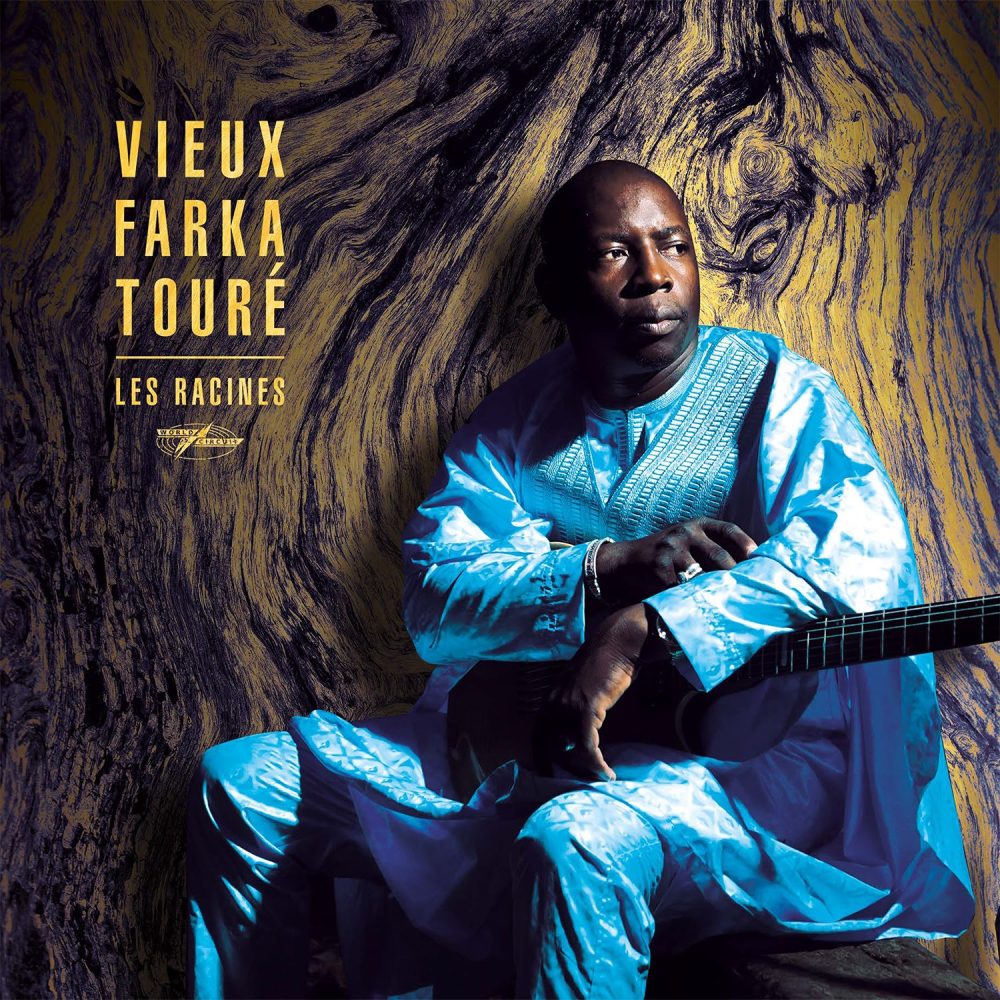

Vieux Farka Touré rocked the house at Race Street Live in Holyoke, MA, on May 22, 2022. The occasion was the coming release of his sixth studio album, Les Racines (The Roots), a deep dive into the traditions of northern Mali in the footsteps of Vieux’s legendary father, Ali Farka Touré. The album is a landmark release in this genre, demonstrating Vieux's mastery of his father's stinging guitar tone and profound knowledge of northern Malian traditions.

The Holyoke performance was the guitarist/singer-songwriter’s 11th in 12 days, and you could guess at the exhaustion when as he performed with closed eyes, but it sure didn't show in his playing, as fiery and passionate as ever. Vieux was staging a spare trio, with Marshall Henry on bass and Adama Kone on percussion. It was the way the artist likes it these days, strong and simple. After adventurous collaborations with the likes of John Skofield, Dave Matthews and Israeli maestro Idan Raichel, the new album is a return of sorts. Before the performance, Afropop’s Banning Eyre and Sean Barlow sat with Vieux back stage for a talk. Here’s their conversation.

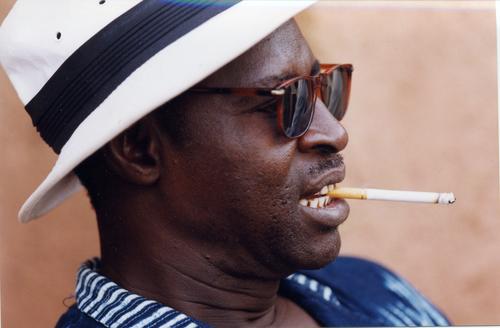

Live photos by Banning Eyre.

Banning Eyre: Vieux, great to see you.

Vieux Farka Touré: Me too. It's been a long time.

It is nice to hear you speaking English. It's come a long way.

I have to learn English. To do this job, you have to learn to speak English. I try to do my best.

For this interview, feel free to speak French if you're more comfortable.

I think I'm going to go to the French. [And he does.]

Let’s talk about this album. What was the idea of making an album called Les Racines. It seems like you're going back to the source on this one.

Well, you know about my beginnings. I started with you guys on my first album.

Yes, I think we covered one of your very first U.S. concerts, at Wesleyan University in 2007.

And you've done a lot for me throughout my career. For those who haven't followed Afropop, I will say that you guys are people who supported me from the beginning. I thank you. For me it's very important to recognize the people who have helped you.

Thanks for that. It’s been our pleasure.

So speaking about Les Racines, I've done a lot of things during my career. I've released a lot of albums that reflect Vieux Farka Touré, not Ali Farka Touré. For certain, I carry the sonority of my father, but I decided early on not to do the same thing as him, but to be myself. This has always been a bit complicated for me. Because Ali is Ali, with his Grammys and all. He's the top. So I decided right away that I wasn't simply going to follow him. I had to let the world discover what I do, what I love, who I am, what I can do. So I have done quite a lot of that. Now, I've arrived at a moment where I said, "I've done all that. People know that Vieux is a bit in rock, a bit in reggae, a bit in pop.” All of that. Many projects. But now I thought it's time to go back home, to reclaim the source, the basis of my music, where I was born, where I grew up, to bring in all of that. And above all, to bring in what Ali gave me as a heritage. It is all of that you hear in this music. On this album, I try to show what Ali gave me.

It's very clear in the music.

Because lots of people have been asking me throughout my career, "Why don't you play your father's music?” And I've always said, "That will come. And for the moment, I have to be Vieux Farka.” But when I do it now, people will say, "O.K., he's returning home."

It's not easy being a son of an icon, is it?

It's very, very complicated. It's really not easy, but people don't understand that. All the musicians I know who have tried to follow the steps of their famous fathers, it hasn't gone well. You have to be yourself. But then, of course, from time to time you can. Look at the sons of Bob Marley. They do their own things, but sometimes they also sang their father songs.

Or the sons of Fela Kuti. A similar story.

Same thing. You have to do the things that you want to do, and then you can revisit the things your father did. So that's where this album Les Racines comes from.

O.K. Let's talk about the songs themselves. Are these traditional songs, new versions of songs Ali recorded, your own compositions?

It's mostly my own compositions. A couple of songs that I have reinterpreted, not exactly reinterpreted, but I've taken something from it as part of my composition. There are some melodies that have been sung for many years. Let’s take “Gabou Ni Tie.” That is me, but inside it there is a song that has been sung in Mali for a very long time. But it's not the same song anymore. When I take an old song from the ’80s, or the ’60s, or the ’30s, whether it was Ali or someone else who sang it, I listen, and I take what I want. And then I use it in my way, and sing it in my way. I take something from that song to create something new.

That's a fine tradition, certainly in Malian music, but in many genres too.

That's it. So “Gabou Ni Tie” is in Sonrai. It says, "You have to know where you are putting your feet.” Today, there are lots of people who just go wherever and do what they like, and the world is no longer at peace. So you have to know where you’re putting your feet. It's very important. When I talk about the roots, I am taking on the role of Ali. Like him, I like to sing about how people live together, about social consciousness, about things that bring about a peaceful life.

Then we have “Ngala Kaourene.” This is a song in Peul that I created. It means, “We must make peace.” We must live together. Because today we have a huge problem between the Peul and the Dogon.

I have read about this. I understand that it’s quite complicated.

It is. For me, as a Sonrai, the Dogon are my cousins and the Peul are my parents. Because in Niafunke there are Peul, Sonrai, Dogon, much more than just Tuareg." And there's nobody in Niafunke who does not speak Peul. We are truly mixed. So I feel like it's time to send a message, a very strong message, that says the same thing from Kayes to Kidal. We must understand each other. There must be peace from Kayes to Kidal. These are the two extremities of Mali. So it's a song that speaks not for the Bambara, for the Sonrai, for the Peul, for the Maninga, for the Maraca… It's a song speaks for everyone.

The song “Be Together” has the same message as “Ngala Kaourene.” Because right now Mali is very divided. The Peul are apart, the Dogon are apart, the Tuareg are apart. This is not good. In the past, Mali was not like that. The Peul and the Dogon and the Tuareg were cousins.

I hear you. That unity was always something I admired about Mali.

It was the system of the Maigas and the Tourés. We knew no war between us, no war among the dialects. We have to return to the old way. We have to live together. Because if the ones who are born today don ‘t know, Mali will come to pieces. If the population doesn't come together, if people want to live separately, it won't work.

The song “Tinnondirene” is also in Peul. It says, “We have to arrive. We have to finish what we started.” We have to be conscious of what is happening and do what we must do. All the people who come, the ideologues and politicians, just turn one group against another.

That's a very difficult situation. What you think is behind it?

Politics. Politics, man. You know, it's a business. Big business behind this stuff. It's very complicated. People used to say, “The Dogon are the rebels. The Peul are the rebels. The Tuareg are the rebels…” I don't know. But I just keep saying that Mali has many dialects, many kinds of people. So if you want to say that it's one dialect that's behind all the rebellion, that's not good. That's a very bad idea. In every population, you have good and bad people. If you want to stop the rebellion, you have to stop saying it's the Peul or the Dogon or the Tuareg. Because now if the Peul see the Dogon, they’re going to kill them. And if the Dogon see the Peul… If you are in a car, not a rebel or anything, but if your name is Diallo or Cise… I don’t know. They can kill you. It’s no good.

So tough. Let’s keep going with the songs.

There’s “Adou.” That’s my son. When I wrote that he was one year old. He was in the studio. This was a song I had not prepared. It just came to me. He was sitting there, it was his first birthday, and I celebrated him in my way. For each of my children, I have dedicated a song. That something I like doing.

Very nice.

“L’Ame” is the soul. These days, everybody is becoming a criminal. There are some really nasty people among us today. Everyone's carrying guns, and they kill people without even thinking about it. It used to be that when someone died it was shocking. Today it's something normal. It wasn't like that. People have to return to their souls. The souls of people are sick. Sometimes it seems they have no souls.

Everything I sing about on this album concerns humanity. I think that today artists must face this scourge. It's true that when you are an artist, it's very nice to sing about love, and everyone likes that. But that's not my path. My art is not that. I'm an artist to educate people, to reflect and bring people to reason. As an artist, I feel I have to explain a little bit what is happening in this world.

You share that with Oumou Sangaré, whom I spoke with recently.

That's it. You can't be an artist and just sing about love and about yourself. Today 80 percent of Malian artists, the young ones, they sing about themselves. Me, me, me. But when you talk about Oumou Sangaré, Kandia Kouyaté, Kasse Mady, Ali Farka, Habib Koite, that's not what they sing about. They sing to educate people. They sing to remind people about the true spirit of humanity. That's it.

O.K. “Flany Konare.” That is about my uncle, the head of the family now. He loves his wife very much. So I dedicated this song to the love he has for his wife. It's a story that helps to understand Ali as well. Because when you love someone, you give them everything, until you have nothing left to give.

That’s real love.

Voila. So then “Lahidou” is in Sonrai. It says there are a lot of people who say they are going to do something, but then they don't keep their word. I might say, “Banning, after tomorrow, I'm going to bring you something." But I never bring it. A guy might tell a woman, "I'm going to marry you. We will live together and be married.” But then he never does. So the song is to say that a promise is a debt. A promise is something very deep and complicated and precious. If you can't provide something, then don't promise it.

These days with us, this is a problem. A young man will say to you a girl that he wants that he's going to marry her, so they can live together. And then afterwards, he leaves. Even our parents did this. I had a grandfather who promised his brother he was going to buy him a pinnace [boat] and all these things, but he never did. And the brother was left to wonder how his brother could live in France and be successful and yet buy him nothing.

The last song on the album, “Ndjehene Direne,” has a kind of ceremonial feel about it. Someone is speaking.

That's my griot. He is speaking about the descendants of Ali and of my descendants. The messages that we must always remember our ancestors. It's directed to all the descendants of Ali. That's why I put it last on the album, because it's partly directed at me.

Let's talk about the music a bit. I really like the flute in “Gabou Ni Tie” and a few other songs. It has a wonderful back and forth with your guitar.

That’s Madou Traoré. I love that too. He’s the flutist for Inna Baba Coulibaly. He is very good. I heard him playing, and I brought them into the studio.

Was this album recorded in Bamako?

Yes. It was all recorded in Studio Ali Farka, at Ali’s former house in Lafiabougou. I made a big studio there, with everything. This is my house now, and I put in a big studio there with isolation booths, everything. We do a lot of great things there. I built the studio in a way to honor Ali, because he always wanted to do things to bring up younger artists in music. All these young musicians now, they want to make music with machines. But we have all the traditional instruments there. So if you want to make a recording with me, you have to use traditional instruments.

Leave the computer at home.

It's absolutely clear. You leave it behind. If you want to make a recording with me, I say, "O.K. We do everything live. No programmation. Everything live." We have ngoni, njurkel, djembe, calabash, everything. Even bolon.

So are there young artists who really want to do that?

For sure. Just the other day I had a call from a young rapper who wants to make his music with traditional instruments. Live. I said O.K. And there are lots of them. For this album, I didn't bring in a lot of extra things. It's very simple. Sometimes we brought in a lot of elements, and the next day I said, "All this is not necessary. Take that out. Take that, take that.” Even the guitars, a lot of the times I just said, “Just one is enough.” I wanted to show people the power of simplicity.

Over the years, you've recorded for a number of different record labels. But now you've returned to your father's label, World Circuit.

Frankly, I didn't want to wait. And I remember that when Nick Gold was there, he said, "I prefer that you make a little tour of the world, work with other labels so that you can do what you want. Because if you come with me, I might block you. It's better if you do what you want."

That was probably wise.

Before I said, “But why not now?” He didn't reply. But today, I understand. He was looking ahead. This time before recording, he said, "O.K., you can join World Circuit." This is an album that will last in the family of Ali Farka Touré and World Circuit. And now I'm in the mode of working fast. Boom, boom, boom. I always want to make simple records like that.

Anything else you want to add?

Well, as of now, I am the president of the Ali Farka Touré Foundation and also AMAHREK Sahel. With AMAHREK, we try to help children, orphans, musicians also, giving them instruments. We have many problems in the north of Mali. When the rebels came in, they broke all the materials, all the equipment. So I tried to bring a little bit each time I come. Because many people now do not want to do music. They're scared.

So now we do the Festival Ali Farka Touré in Bamako. We bring musicians down to this festival, and let them do what they want to do. If you go to my website under Activism, you will see what we are doing. So we try to do our best. And now, they've recently given me the honor of being an ambassador for Save the Children in Mali.

Congratulations. That's great stuff.

I try to do my best. I'm a musician, but what can I do for the kids? For me, the honor comes when I actually do something for them. We have some 200 kids in Timbuktu, and every year I send books, notebooks and things like that. Those people don't have money. If you're a father and you have less than one dollar to feed your kids in one day, and then you have to buy books and school supplies, this is why many kids don't go to school. Because the father says no. “I need to feed you guys. So don't go to school.” When I saw this, I knew what to do.

So I spoke to my manager, Eric Herman, and we decided that for all the CDs that we sell, we would take 10 percent for the foundation. That's what we do. We also bring things on tour to sell, to try to raise money to help these guys. Sometimes people give us money on the website. Not long ago we played in Seattle, and someone who came to the concert gave $2200. And everything we do, we post pictures on the website. Because when people give money, it's good for them to see what that money is doing. How much we raised, what we did with it, everything is there for people to see. That's very important.

Thanks so much for talking with us, Vieux. We’ll let you get ready for your show now.

Thank you very much.

Related Audio Programs