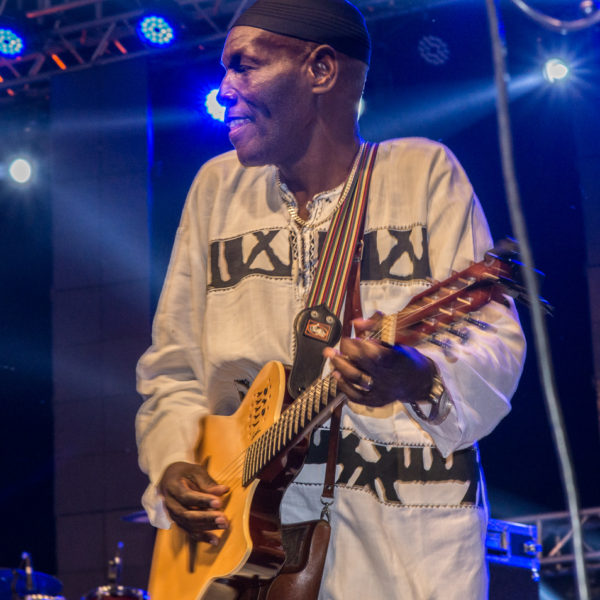

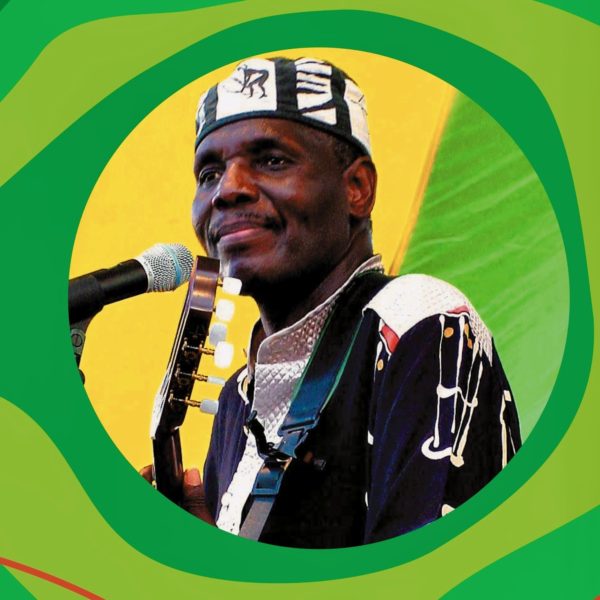

These days the music scene in Zimbabwe is dominated by Zim Dancehall stars and deejays. But that doesn’t mean traditional group and roots pop bands have disappeared. We recently met WaCharie, a singer/guitarist/songwriter/bandleader, born in 1992. WaCharie writes serious songs and has a band sound strikingly reminiscent of the late Oliver Mtukudzi’s. Afropop’s Banning Eyre recently spoke with WaCharie via a video call from Mutare, a town in eastern Zimbabwe near the border with Mozambique. WaCharie has recently released his third album, Chidzorogoro, a strong set of twelve thoughtful songs with grooves that can only have come from Zimbabwe. Banning was instantly a fan. Here’s their conversation.

Banning Eyre: Hey, WaCharie. Where am I reaching you?

WaCharie: I'm in Mutare right now, yeah. I'm actually here with my manager, Kevin.

Cool. Hey, Kevin. So, WaCharie, I want to hear your story, how you became a musician, where you grew up, and all that kind of stuff.

Alright, well, let me see where to start. I'm WaCharie, born Tawanda Charie. You know, where I come from, people didn't really know my name, they only knew my father's name. So they used to call me Mwana Wa Chari, meaning “son of Chari.” But it became too long for them so they just started calling me WaCharie.

I come from a family that loves music. Growing up, I was surrounded by music, all types of music, from Western music to local traditional music. There would be music every day, from early in the morning until late at night. I really loved seeing people happy, what music did to people, how it made them connect, brought them together, even when they have their differences. Whenever there's good music around, people get along and just have fun. So I wanted to bring that into people's lives. I can't really say I decided to do music. I think music decided for me to do it. I actually tried by all means to run away from it. I tried by all means.

To run away from it? Why?

I wanted to do different kinds of things, but I always found myself right back trying to do music again.

What was your first instrument?

I've always been passionate about the guitar, but know, growing up here, where we come from in Africa, music is quite demonized. Being an artist, even though people love music, seeing their child doing music is something they don't really accept. You have to do all the other things, but not music, so I didn't have access to an instrument until I was around 20, 21.

Wow. That long.

Yeah, that long. Then I found a second-hand guitar, which was dead. It was dead, like you played all the strings with buzz. But you know, I was passionate and I started teaching myself. I'm self-taught, if there's anything like that. I believe we learn from the people around us, by watching. So I started teaching myself guitar and from there I started teaching myself mbira. I started playing percussion. I was all over the place, but I was happy that I was finally getting to do what I really loved.

This is in Harare?

Yes, in Harare. I grew up in Harare.

You said you grew up surrounded by music, but were your parents musicians?

No. I think everything musical that I have, I took it from my mom's side, not my dad. He's late now, but he didn't want anything to do with music.

I’ve heard stories like yours a lot in my work with Zimbabwean musicians, stories about parents who did not want their kids to be musicians.

It's the Zimbabwean story, yeah. But, you know, having grown up, I went to South Africa looking for greener postures. You know how things are economy-wise in Zimbabwe, and I decided to go and look for something to do in South Africa. I had no plans to perform when I got there, but I practiced a lot. I was always on my guitar, practicing. So there's a guy who saw me playing on Facebook. He was in Cape Town and I was in Joburg.

He was like, “Man, come over here. I want to work with you.” I said, “Man, I'm not really a musician. I do this for fun.” He said, “No I want what you're doing.” I thought he was kidding, but a couple of days later he sent me money for transport and I'm on the bus to Cape Town. I get to Cape Town to rehearse the guy’s music. I was supposed to play guitar and he was doing the singing. So when we got to the venue, and I was supposed to do soundcheck for my guitar, I didn't realize the venue was already packed. It was a big hall and it was dark, you know? The light was on me on the stage. I switched on my guitar, I started doing the soundcheck, the engineer saying, “Okay, play something.” And then he says, “Can you sing?” I said, okay, fine, let me sing something, since there's no one in here. I did one of my songs. Just after doing that, the lights went on and the hall was packed.

My God! I couldn't even play the second song. I was shaking. I was shaking and he said, “No, keep playing.” And people applauded. They loved what I did and then they said I had to keep playing. I played I think about four songs and people really loved it. That's how I began. That's how my journey began.

That’s quite a story. When was that?

It was in 2014, 10 years ago.

And so from that moment, you thought, “Okay, maybe I can be serious about this.”

Actually, I wasn't given a chance to make that decision because it was made for me. Just after that event, I got a booking. I was supposed to play the following day and at that gig I also got a couple of bookings. I didn't really have time to think about it. I just got into it.

Fascinating. So the songs you played were ones you had written?

Yes, yes, songs I've written. Before I even started playing an instrument, I used to write songs. I would just put something down, try to shape it in a way, trying to make it sound good and all that. So those are the songs I did on that day. I had practiced them over a million times. So they were really ringing in my head all the time.

How did you get from there to forming a band?

I remained in South Africa for about a year. Then, towards the end of 2014, I decided to come back home. So the moment I came back to Zimbabwe, someone had heard about me when I was in Cape Town. They had an anniversary of some sort, and they invited me to play at their anniversary. They gave me a band, their band, which was supposed to back me up on that day. So just after playing at that event, the whole band approached me and said, “We want to play with you.” And that's how I got my first band.

They heard something great. Now, this album that I'm looking at now, your latest. I’m seeing NeShamwari Dzerwendo. Tell me about that

Neshamwari dzerwendo means “the friends we travel with.” That's the name of my band.

The album title is Chidzorogoro. I really dig the tunes. Your singing is beautiful. Your guitar playing is lovely. How many albums do you have?

This is my third studio album. This is my own band now; this is the band I perform with. I meet people in different places. I'm always looking for interesting characters. So before the music aspect comes in, I look for people I connect with on a personal level, people who quickly get what I'm trying to say before I even say it. I don't have to struggle explaining to them what I want to do. We are kind of resonating in the same frequencies at a personal level. So when we get to the instruments and the music, it's easier to connect. Most of them, when they came, were not really as perfect as they are now. But because of the personalities and the characters that they had, we became one and we started teaching each other up until we became the unit that we are now.

I hear a lot of the influence of Tuku, Oliver Mtukudzi, in your sound: the acoustic guitar, the interesting traditional rhythms, the structure of the songs. Was he a role model for you in any way?

Very much. The man is pretty much my biggest role model. Almost 90 % of what I know in music I have learned from listening to his music and from hearing him talk. He is great in every aspect. He influenced me in telling me to be who I want to be, giving myself to the people and not trying to be anyone else.

Did you know him?

We met a couple of times. I went to his place because there were programs he used to do, grooming young artists and stuff. So I met him a couple of times I got an opportunity to sit down and have a chat with him.

I think if he were around, he'd be very impressed with what you're doing. Let’s talk about some of the songs, the messages and the rhythms. In the past, I was more familiar with all these different Zimbabwean traditional rhythms. I've gotten a bit rusty on it. I feel like one of the problems with music these days is that too many artists gravitate to the same rhythms. It's almost always the four on the floor or some clave variation. I like interesting rhythms, and you’ve got them .

Yes, true. Thank you so much. Mostly my rhythms are influenced by traditional grooves, but then my thinking is kind of not straight. I struggle to think in a straight way musically. So I try to put them in a way that does not confuse people but rather gives a heartbeat to the sound. My main focus when I'm creating stuff is usually the bass and the drum. The soul of African music is the rhythm, the drums and the percussion and everything around that. I think having come from a traditional background has really helped shape that part of my music.

Tell me about the song “Chadzimira.”

“Chadzimira” is a prayer. We believe in some way, at some point, we will get to a place where we feel lost and we're trying to find ourselves and connect to a greater power. So this was me saying to the creator that I'm lost, “Help me find myself, show me the way.” As far as the rhythm is concerned, I'm sure you're familiar with katekwe.

I know that’s one of those rhythms Tuku liked to use.

I'm from the same rural area he is from, from Dande valley. Katekwe came from Dande. So we have the same roots as far as music is concerned. This is the music we hear when people are celebrating something, when people are happy, when they come together. So that music, that drumming, influenced the sound and the rhythm of “Chadzimira.”

It’s a cool 6/8 groove, but tricky. You can hear other rhythms within it. Very deep. How about the title track, “Chidzorogodo.” This one also has that rhythmic complexity. You can count it in either 6 or 4. Both are right. I love that.

Yeah, yeah, yeah. Growing up, my great-grandmother, the mother to my grandmother--she's still around and very old, by the way—she would say that when you talk about something or when you smile or laugh without even knowing what you're laughing about, oh my, you will be in trouble. She would say, “Chidzororogodo. You're talking about me behind my back.”

I realized that in life, there are people who think everything is about them. When someone succeeds in life, they think this person’s success is something to spite my failures. There are people who think that if things are not going well for them, then someone else whose things are going well should not celebrate. There are people always think everything is about them. So that's “Chidzororogodo.” It's on the same katekwe rhythm, but with different placing of the kick and the snare.

I hear that. I love all these songs. Are there any you want to talk about particularly?

There's a track called “Ndambakuudzwa.” That one has a bit of a groovy rhythm. At first it's broken down and then it's groovy. It talks about people who don't listen. There's a proverb in Shona that says Ndambakuudzwa is the name given to someone who doesn't listen. So they are seen with a scar on the forehead. Because they don't want to listen something happened to them and now they have a scar. There are consequences. You've got this scar on your head because somebody told you: don't go in the darkness, but you went and you hit your head on a post. Now you come back with a scar. I gave it a groovy rhythm so that the message does not get lost in the seriousness. People don't really like serious stuff, you know. They want stuff that can make them happy and dance, but at the same time, the message doesn't have to get lost in the beat. So I was trying to make sure that it gets to the people, but whilst they're enjoying themselves.

That's a very interesting thing, putting a tough message into a sweet tune. I always think of Bob Marley. “Total destruction the only solution.”

Yeah, yeah. If you put it on a depressing melody, then nobody will want to listen to it. No one wants to be depressed. And then we did a track called “Muninga.” I think it's the shortest track on the album. It is kind of a mental health awareness song. People are going through a lot out here. Almost everyone is going through a lot. So it was about someone saying, “You see a smile on my face and you think everything is okay. But no, it's not.” These days in social media, people are always saying that they are there for you. They are there to listen, you know? But when you say something that's really happening to you, you meet a lot of condemnation, a lot of negativity. But they are the ones who were saying, “Talk to us.”

Really? They want you to talk and then if you open your heart, they attack.

You’re giving them a point to attack. Now they know that someone is going through this, they’ve got an angle. That’s the way of the world. And we kind of try to put a rhythm there that doesn't depress you, but you get to listen to the message. So that’s “Muninga.” Then there’s “Mskanzwa.” That's the only track that is not traditional on that album. The rhythm and the grooves is more pop, jazzy, in a way. I wanted it to appeal more to a young audience. It's talking about mischief, people who are cheating on their partners. “You guys, why are you doing this?” It's one of the most popular tracks in the clubs. That's what they love to hear about.

Sure. Infidelity is always a very popular theme.

Then we have “Mharadzano.” That’s a track about someone who says, “I’m coming to the end of my journey.” Mharadzano is kind of separation. You are going this way, I'm going that way. It’s a crossroads. I'm saying that I've come to a crossroads with myself and my troubles. I'm going this way, and the troubles are going this way. That one is very much traditional. It's quite close to my heart. I put in a lot of work into that one.

I can see that. I look forward to listening again with all this in mind.

Please, please do. And then there is, “Mbwende.” It means coward. It's talking about gender-based violence. So I’m saying that if you see someone who hits someone, that is a coward. They want to avoid conversation; they have nothing to say; so they resort to violence instead of talking. The head is empty. They can't say anything, so they will hit you. I don't know if it happens over there, but this side, there's a lot of gender-based violence, people are always fighting in married years and stuff, and at end of the day, people are getting hurt. Both men and women. They're getting hurt because of the fighting, so I was trying to find a way of dealing with that.

Good for you.

Then there is “Chati Homu.” That comes from a Shona proverb. You know, baboons make a sound like that goes like, “hom heem hum.” They'll be communicating, right? So I say, “When someone says something, they have communicated something. It's up to you to listen to them or not. It's up to you to consider what they have said or not, but they have communicated.” Oftentimes we misunderstand each other, but then we say that someone did not communicate, but they were communicating. We were just not paying attention to them. I think that is the slowest groove on the album. I wanted to be a little bit relaxing.

That theme of wanting people to listen to each other runs through this album. The person who doesn't listen and has the scar and the couples that need to listen to each other. It’s kind of a unifying idea.

Very much. Very much. I've learned that there is always a need to put a message across to people and the best way we can do it is through music. That's the only place where one doesn't feel condemned or rebuked or attacked.

How do you go about writing songs?

Well, it starts with me. Most of my songs I write myself. Then once I'm done with the music, I come to the band with what I've created. I say, guys, “This is what I have. And I want you to go like this, like this, like this.” Then when they've done what I've said, I give them room to express themselves. Then they start doing what they can and we come together with a beautiful project.

It's clear that you guys work well together. It’s such a coherent sound. Who is your audience in Zimbabwe? And what kinds of venues do you perform at? I remember the days of beer halls and nightclubs all over the city.

Well, I got to a point where I wanted to classify my audience and put them in groups. I wanted to group them according to their ages and stuff and then I realized that: no, I'm wrong. Actually, people listen to my music from different age groups and different ethnicities and different backgrounds. So now I try to make my music the common thing that brings people together instead of their age, or their backgrounds or their ethnicity.

I've been playing in quite interesting places. We have a concept we recently developed whereby we do house concerts. You play for a certain community. You see that these people love my work. They come together, a few families, you know. They find a big place. We go in and we do music there. In the clubs? Well, we have a few bars that we play in, but this thing has kind of changed, it's kind of shifted.

In the days of Thomas Mapfumo and Oliver Mtukudzi, the music scene was dominated by the live band musicians. These days it's more dominated by the digital musicians, the ones who do digital genres. It's quite difficult to penetrate that space for different reasons. One of them being the venues do not accommodate a live band setup. So it's quite a struggle. We've had big shows, on big stages, where they don't even have a drum set. That's one of the main challenges that we have now, being a live band musician.

Wow, that is a big change.

This era is quite difficult.

I'm sure there are people who still really want live bands, right?

Very much. Very much. We are playing almost every weekend. This weekend we had something on Sunday, on Saturday, this following Saturday. We have a gig. Sunday we have a gig. And the following weekend again.

You probably have your own sound system, right?

Right now we hire sound systems.

And you’re mostly doing these community shows.

Those are most of the gigs that we're doing. But we're also playing in bars and beer halls. People are coming out in numbers, you know?

That’s great. When I first went to Harare in 1988, you weren’t even born yet. But I couldn't believe the number of bands that were playing all over the place and everybody was really good and big crowds came out and supported. It was exciting. It was also very competitive, and the music was excellent. Thomas and Oliver, Simon Chimbetu, John Chibadura, Leonard Dembo, Leonard Zvakata, The Four Brothers, on and on.

We wish for those times.

Of course. But someone like you who's young, and who's really carrying on the tradition of a strong live band, can make a difference. I love that. I'm glad to know you’re there and reaching people of different generations.

Thank you so much.

Do you get to play outside of Zimbabwe?

The only time I played outside of Zimbabwe was when I started in South Africa. But now we want to expand and reach beyond our own border. This is what we are working on now.

I guess the obvious place to start is the UK. You've got a really great sound and I know there's an audience for it. Maybe maybe more on the outside than the inside. Who knows? You'll find out, I guess.

Hopefully, and with the feedback that we're getting online from the album and everything else, I'm really hoping that outside is much better than it is locally.

Me too. I'd love to see you guys over here. We will stay in touch.

Related Audio Programs