Weedie Braimah is a djembefola (a master of the djembe drum), and a force of nature. Born in Ghana and raised in East St. Louis by two world-class drummers, his father Ghanaian and his mother American, Weedie imbibed deep percussive knowledge pretty much from birth, and he’s kept learning ever since. As we’ve noted on this site before, Weedie has expanded the range of his instrument from an accompaniment role to the central player in his powerful band, Weedie Braimah and The Hands of Time. After a recent performance of the band at the Blue Note in New York City—with the phenomenal Cuban conguero Pedrito Martinez sitting in—Afropop’s Banning Eyre caught up with Weedie for a talk about his current doings, including taking students to West Africa—damn the politics!—to study with local masters. He also previewed a collaborative recording he recently co-produced with Michael League of Snarky Puppy for none other than Youssou N’Dour!. Here’s their conversation, lightly edited for clarity.

Banning Eyre: Hey, Weedie. Great to talk with you again. Are you still based in New Orleans?

Weedie Braimah: Actually, now I'm between New Orleans and Ohio. I basically live in Ohio. My family is here, and I'm an associate professor at Oberlin Conservatory of Music. So we have some unique courses there, Djembe Orchestra and Djembe Practicum taught with me and my partner, my wife, Talise Campbell, who's a professor of African dance.

We have an African dance ensemble at Oberlin, and I'm over at the Djembe Orchestra. We teach students how to play for dances and how dancers are able to understand the music and understand both narratives. And then we have the Djembe Orchestra. I think next fall semester, we'll have a band that's gonna fuse folkloric Manding, Akan, Asante, Ewe and Yoruba music into modern narratives and genres. We’re going to be able to mix those within the jazz vernacular and blues and funk, pop, hip hop... So that's the next thing. But right now, it's over 38 students in the class at Oberlin, and I'm really proud of those young kids. They sound great.

That’s fantastic.

You know, they go to out with us to West Africa. We’ve taken the kids to Senegal, we took the kids to Ghana, we took the kids to Mali. We're actually working on our upcoming trip to Mali. We’ll be in Bamako with all the who's-who's that you know.

How do you find it om Mali now? Have you been recently?

I was just there last year, but I'll be back again, God willing, in another couple of weeks. One thing I know will always stay true is that the music still lives; the culture still lives. Through all the barriers, it's the music that makes the ties that bind. And that's been my heartfelt understanding. Politically, we have issues everywhere. Hell, we're in the States! But I know the people. If you have a passport to the world, you know there's issues everywhere. But as an African raised in America, I've realized the struggles on both ends of the water. The only thing that separates us is the water.

I imagine you might get some pushback from the parents of those kids.

Oh, we did. We did. We definitely did. But this is not through the university. My wife and I have our company, DJAPO West African Dance Ensemble/Cultural Ensemble. She had this way before we got together. So me and her, when we got together, we were able to bridge ideas. I was the first one to take her to Mali, because she's been to Senegal 30 times, 40 times. She's basically Senegalese, and so with me we started going to Senegal, going to Ghana and going to Bamako. , Bamako is a special spot. You have to go there to see how special it is, to really grasp it. And once you grasp it, that's it.

So true. I hear you on that. But our wife's company? DJAPO?

It means “coming together” in Wolof. She started it about 16 years ago, and we met eight years ago, right when I was touring like crazy. I had left the drum and dance world. So when she started DJAPO African Ensemble, we knew each other from afar. She's been able to train a lot of artists, teaching them to preserve the traditions and the cultures within the narratives in America. I'm very proud of her for that. And you know, our little one is a phenomenal musician. He's an honorary Ghanaian and an honorary Malian because in Bamako, that's his home. He loves Mali.

Beautiful.

So we take 21 students to West Africa, students and fans. Some people are my fans, and they want to come and study with me in Africa. It was not easy, but at the same time the people there respect us and they know we have our child with us. So they would not put their child in any harm.

Okay, well that's very exciting, and you're going soon.

Right after the new year begins. The students will be in Senegal for a week and they'll be in Bamako for a week.

I was once in Bamako for New Year's. It was fun.

Me too. It's a riot. It's a hang. The musicians are going from one gig to the next. One sumo [griot music ceremony] here, one naming ceremony there. That’s their money night. That's a money night for musicians all around the world, I think.

Absolutely.

So it was great seeing you guys at the Blue Note. What's going on with The Hands of Time? The last time we spoke, the record was just out.

Yeah, the record came out. It did a couple of cool things. We got nominated for the Grammy for Best Jazz Soloist for our brother, Chief Xian aTunde Adjuah, formerly known as Christian Scott. We made the top 10 albums in Time magazine.

Wonderful.

It was cool. But the most important thing, Afropop Worldwide loved it. That's all I cared about.

[laughs] Yeah, right. And on the strength of that, you've been touring. Where have you played?

We just got back from Europe. We're heading to South America in February. Hopefully, we'll be in Brazil, in Rio and Sao Paulo, then Argentina. And there’s some other cool things coming at the end of the year that I can’t talk about yet.

Nice.

But you know, my main goal is to maintain the instrument in its purest presence and to show what it can do. A lot of times we always get talked about as “the percussionist.” I don't understand that, but then I do understand it because that's the way we have to introduce instruments with a European vernacular. When we try to define a European vernacular with an African narrative, it just changes up everything. My band is a testament that you don't have to be the guy playing in the back. Most African djembe players that come over here, they're in the back or they come out at the end and solo and the crowd goes crazy. Wow! And that's it. The difference with us is that the djembe player is the lead; it's the melody; it's the heart of the band. That means if I don't come, the band ain't coming.

That was very evident in the show we saw at the Blue Note. You are front and center, leading it all.

If you look at bands like Mamadi Keita with Sewa Kan, it was a djembe group, but still under the vernacular of djembe rhythms. But what he was doing was very futuristic. He was utilizing these rhythms and spaces that you wouldn't see. He was playing all these different international festivals. But during these festivals, they noted him as being the grand percussionist. You know what I’m saying? I want to change the narrative. Yes, all these other percussionists are out there, phenomenal, world-class percussionists, and they're great. But when we played at the Blue Note the other night with our guest Pedro Martinez, the statement I wanted to make is that you have to know this gentleman as a conga player. He's a congero who's in the richest and the purest tradition of Afro-Cuban music. And to say that he's just a percussionist… Okay, he plays some shakers’ he plays this and that. There are percussionists in an orchestra, but within the orchestra, they list the items you play. If you are in the woodwinds, you play oboe or clarinet. I am trying to change the narrative for percussion instruments. If you're a percussionist, you play marimba, you play snare, you play congas, timbales, bongos, triangle. You play vibraphone.

I play an instrument that has a name. I've never seen a person say, “On drums, Max Roach; on piano, Thelonious Monk; on percussion, Chano Pozo.” Thelonious Monk, Max Roach, Art Platt on percussion? They all are part of the percussion family.

Of course. People don’t think of piano is a percussion instrument, but it is.

Exactly. But if you call a drummer a percussionist, he will immediately get mad. So that's the narrative we're changing.

You know, what I thought was interesting was when you guys played “Sakadougou,” a classic Mande piece, I was listening to the way Pedrito played within that, because that's a tradition that's sort of peripheral to what he does. It's a separate branch of the tree, as it were. So I noticed that every time he played, I heard this Cuban inflection in it. He wasn't wailing and playing fancy stuff. He was just kind of commenting, but it was adding this very particular Cuban texture. That was great.

Exactly. And it was a real shaking of hands from across the sea that was happening. My idea is that I'm literally a bridge. Who I am, how I was born and my history is a bridge. First of all, there's a lot of folkloric Ghanaian drummers who play djembe. But djembe is not an indigenous instrument to Ghana, historically speaking. Now everybody loves the instrument, but with everybody loving the instrument, we have to interpret how to respect and get a certain type of knowledge behind it, so we can pass it on to people who don't know.

So when we do gigs like this with Pedrito, Pedrito is singing in real-time. It’s a style of music that he can appreciate as a listener, but not as a practitioner. And that's different. So now, something interesting happened during that show when we were playing “Sakadougou.” He was listening as a musician. He’s listening as a melodic musician, listening to what will fit and what would be able to speak to him. And we talked about this every night. The whole band knew that something that unique happened.

So the beginning part, when we play a real serious Mending folkloric groove, that's straight “Sakadougou.” Straight. I didn't want to play with him like I was just playing with a person that played congas. I wanted to play with him as a djembe player who understood his narrative. I wanted to speak to him as if I was playing with another person in Cuba. I don't want him thinking, “He's a djembe player; I'm a conga player.” Because my job as a djembafola is to be able to speak multiple languages and talk to the person in their language so they're able to follow me in my language so we can speak together. So within my djembe phrases, I'm gonna play calls and codes that understand that he's playing Abakuá [Cuban religious music]. He's playing rumba, or he's playing bimbi, or he's playing all these folkloric Afro-Cuban rhythms. But on the flip side, he then threw it back to me.

Then, when we went to the mbalax rhythm in the second part , he start playing the mbalax groove on congas. And if you ever watch the video from this, you see our faces. The whole band was like, wow! We lost it. And he stopped, ‘cause he's like, “Did I mess up?” He naturally played the phrase that he's supposed to play. And when we went to the dressing room, I said, “Yo, you so-and-so! Did you know that's what you were supposed to play?” We cuss each other out all the time. We're very close friends. And he’s like, “Man, I thought I messed up. Did I mess up?” I said, “No, bro, you played the exact part that fits with the music.” We've done a lot of shows together, and a lot of people always want to watch us play together. But what I did at that moment, which was touching, was that I wanted to play rhythms that made him feel comfortable within the group, so he could feel like, “They're playing my language.” And so he did that, but it was almost like a baseball game. He pitched it back to me immediately. And I'm like, “Whoa!”

Yeah, that was impressive. I could see that happening. When you hit the mbalax part, that's a very specific thing.

That's a very specific thing and you either know it or you don't. And he knew it.

Speaking of innovative versatile percussionists, we just lost a great one in Zakir Hussein. That was a shock, right?

That man, he was the king, the king of tabla. I know there's other people out there that are like the next big thing, but the innovativeness of what he did with the instrument… he took it everywhere.

He was a tabla player, not a percussionist, right?

Yeah. My dream is to be like that; I wanna go even farther than that. You know, Adama Drame (virtuoso djembefola from Burkina Faso)? When he heard my album, he was like, “Great work, very great work.” My job is to pray and pray one day I can even get even close to what these greats have done with the instrument.

Well, that's humble of you, but I think you're well on the way.

No, I'm praying. I'm praying. I want the instrument to have the name and the recognition, like congas. And it's getting there. It's getting there. Now, of course, there are more drum circles in the world and everybody knows what a djembe is. It’s everywhere. People ask me about drum circles and I'm like, I'm not a fan of them. I can respect them. But I’ve never seen a piano circle. I've never seen a tabla circle. And it's because of respect for people like Zakir who made people realize that this is not an instrument that you can just take to a drum circle and play.

I see what you're saying. You've never seen a tabla circle.

And I never will. But that's the issue I fight every day. We cannot just use an instrument because we feel something. I've never seen a violin circle either. You have to go to a certain classroom and learn from a teacher and people pay $150 an hour for their child to learn how to play violin. So why not pay that same $150 to a djembafola who understands how to teach your child, and not just how to play an instrument. We're not teaching life skills when you're learning violin. I've been to school for music and I've never learned life skills. It was the people who believed in me as a musician who said, “Okay, come with me.” I come from a musical family. Those were the ones that loved me and said, “When you're becoming a young adult, you have to conduct yourself like this. Dress like this. Eat like this. Play like this. When this person walks in the door, you present yourself like that.” That's why it's important for Zakir Hussein's legacy to forever stay alive.

And I believe it will. The man opened doors you can’t close.

You know, we did this unique show like a year ago at the Blue Note. It was with Savion Glover, Chris Dave and myself. It was tap dancing, drum set and me on djembe and congas. It was actually one of the most interesting and most emotional shows I've done, because I have the biggest respect for Savion Glover as a tap dancer and as a hoofer and the biggest respect for Chris Dave as a drummer, an icon of our time. And for them to do that show with me, it's a testament that they see the respect for the instrument.

Sure.

I don't want to be confined by the barriers of time because I have to do X, Y, and Z. I don't want future students that see me and say, “Okay, I have to play this in order to do this.” I don't want my son to be like, “I have to do this to make it as a musician.” I want him to learn everything, to be a full-round musician.

The last time we spoke, you mentioned that you had done a special project with Michael League of Snarky Puppy. Is that something you can talk about?

Okay, here’s the story. It's not a Snarky Puppy project. Michael League is producing a project that I am co-producing with him. We wrote, arranged for one of my heroes, and to me, it really changed the narrative of the future of African music. Mike League and myself just produced the next Youssou N’Dour album, which is coming out I think in February, 2025. We did it in Spain, in Calaf. We were at Michael's house, in his studio. it was one of the most surreal moments. Banning, I've done a lot of projects that I wrote for, produced, co-produced, or arranged. I've done a lot of things. But as a djembefola, to write and arrange with Michael League, who I have the biggest respect for as a composer... I take composition very seriously, and he’s an amazing composer, amazing human being. We're in a band together called Bokanté.

Right. I've seen you guys. Terrific band.

Here's how it all happened. We were at Essaouira (Moroccan seaside town that hosts a massive annual festival of Gnawa music), and he had got an email and said, “Bro, you're not gonna believe this. I just got asked to do the next Youssou N’Dour album.”

And my whole body, my heart, just said, “Wow, I wish I could be a part of this.” So a couple of days later, I said, “Hey, Mike, I need to talk to you about something. I got a big favor to ask.” And he's like, “What? Anything for you. We be with brothers. Of course.” But I couldn’t. I said, “I’ll tell you later.” We were there writing for the next Bocanté album. We stayed there after the festival. So we were leaving, going to Germany. And on our way to he says, “Weedie, is everything all right? You said you need to talk to me.”

So I say, “I need a big favor. Let me be a co-producer on that album.” And he looked at me, he says, one 1000, two 1000, “Done! I was gonna ask you to be a part of it.” But how unique the way the world works! Everything happens by divine intervention, divine choice. About a year ago, I met Youssou’s manager Dudu Sarr. Dudu is a friend of mine. We had dinner with my students when I was in Senegal. And when I got back to the United States, I sent him a video of us at the Blue Note, that version of “Sakadougou,” and he was like, “My God, bro, this is classic mbalax. Can I send this to Youssou?”

I thought it was a joke, right? Now, mind you, I'm the biggest fan of Youssou, but I'm also the hugest fan of his sabar player, Mbaye Dieye (Babacar) Faye. Mbaye Dieye Faye is the reason why I am the quote unquote the percussionist than I am today. When you talk about percussion in a band, he represents how to be a leader and how to be a composer, and how to be a percussionist within a context like that. So when people ask me who's my favorite percussionist and folklorist, I will forever say Mbaye Dieye Faye. Forever. He is the king of that. And he's a comedian. He's the star of show. Youssou’s the star. But Mbaye Dieye? People go crazy.

Right. He's the one who revs up the audience.

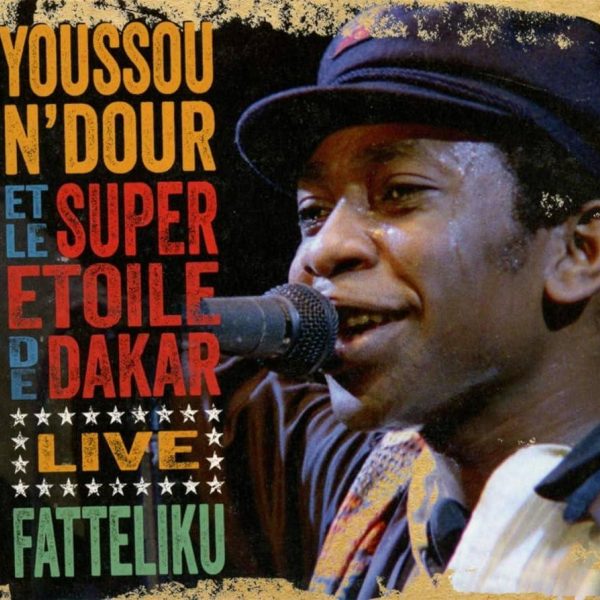

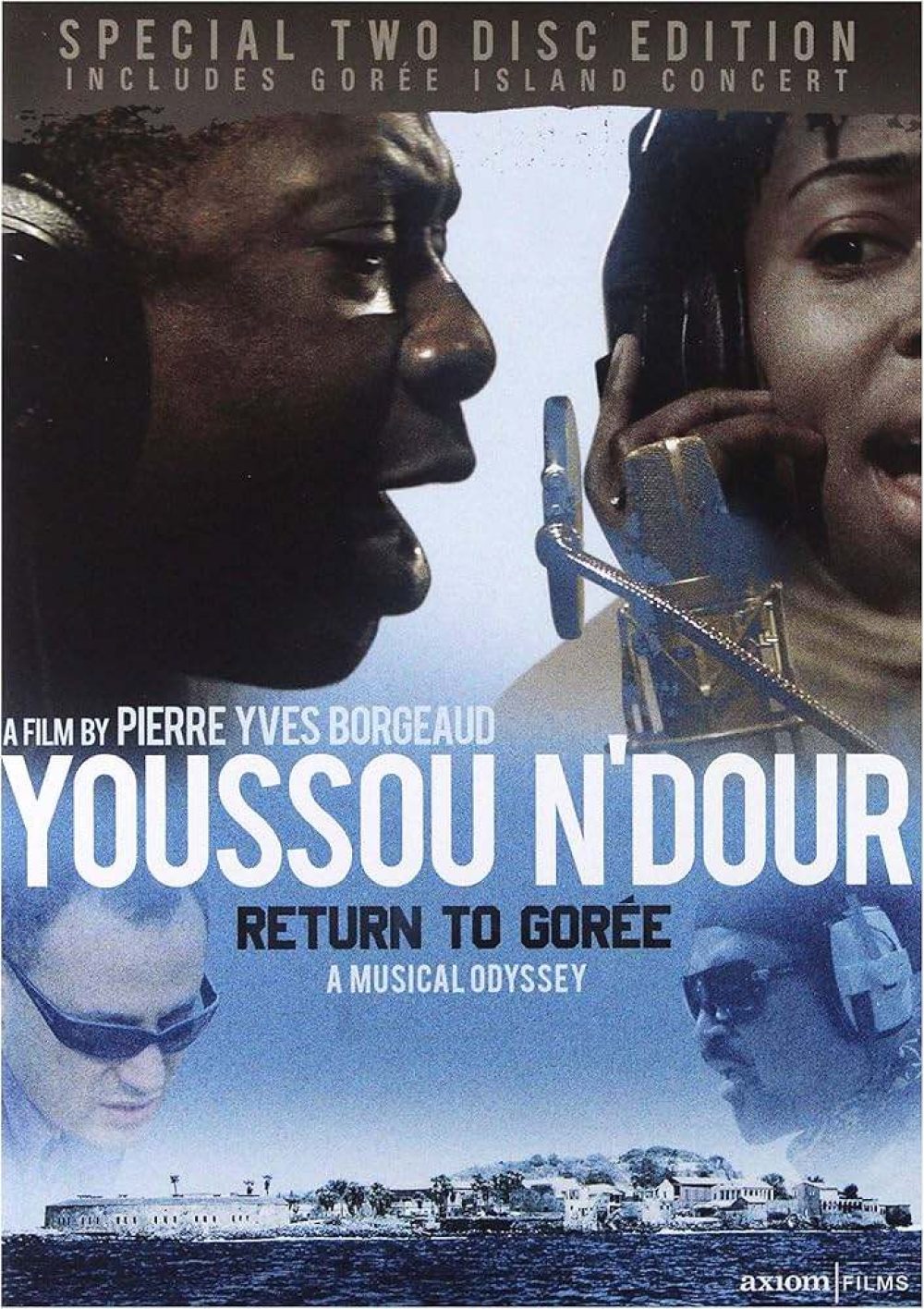

Within my show, I do one of Mbaye Dieye’s songs from his album, Songa Ma. I pay homage to him. So I met Dudu and when Dudu heard that he said, I have to send this to Super Etoile. They're not gonna believe this. So he sends it to Super Etoile. So later, I’m on my way to do the Blue Note Jazz Cruise and I get a call from Dudu. It's Dudu talking to Mbaye Dieye and Mbaye Dieye says, “Weedie, my son, I've been watching you for years, man. And I know your family. You know my family; we talk about you. They love you. We watch your videos, man. You are family.” So it turns out Youssou was watching the video too, and he told Dudu to send me a message saying, “Great work. Who is this kid? I love him.” Long back, Youssou did an album with my uncle, Idris Mohamed, the jazz drummer, called Return to Gorée (an album and a film from 2007).

So Dudu Sarr is the one who reached out to Michael League. Dudu has no idea I'm a part of this. So all of this is going on and we gotta get the band together, including my hero Mbaye Dieye Faye. Now it was time for my dream to come true. So when we met with Youssou in Calaf, I shook his hand and he looks at me and he says, “I know you, I know you!” And we hugged, and from that day, with Youssou, I can honestly say I didn't just gain a friend. I didn't just gain a hero. I gained a father figure, a papa and a true family member. It was something special.

What a story. So this album, is it a combination of Youssou’s compositions with Mike's and yours? How did it work on the composing side?

That's basically what it was. That’s exactly what it was. It's Youssou, Mike and me. I would say Mike is a visionary. I was almost like the glue, because Mike researches a lot. Mike would send me some things to listen to. I knew things visually to let him see the instruments we could use, because I new this world. One thing that helped me to blend folkloric African music to modern narratives was my last album. It didn’t just come from: let's get this guy and that guy and let them play together. It's a new sound. You have to speak both languages to create a new voice. If this had been Mike by himself just playing mbalax, Mike would have done a great job. But mbalax is a different beast. It’s a way different beast, even just understanding where to land the one. That's your first challenge.

Like we said, it’s very specific.

So we were in the studio, me and Mbaye Dieye and Assane Thiam and Munir Zakee, and we’tr there playing together. But the best part was it wasn't just: okay, let me find where the groove is. Because we all knew each other's voices, it was like hand in glove. That was the beautiful part. What we thought was gonna take us three days to do, we did in a day and a half. Youssou, Mike and myself already had a lot of songs that Mike and myself had arranged. And then the songs that Mike and me brought, it was like building from the ground up. As I always say, Mike is a forward-thinking person. And some things I would look at Mike, like, “This may be toofar out.” But thank God I had the understanding of how to make it work rhythmically as well as harmonically and melodically. So there’s a lot of things that Mike and me had ideas and Youssou’s like, “Spot on.”

It's a testament to djembefolas that we are able to create and write and compose, not just because the Hands of Time album, but truly writing, composing these pieces for artists and icons. One of the deepest things I'll never forget in my life… There's some songs that we did that I had to show Youssou the idea. I don't get nervous, but to teach your hero the melody to something and hear him saying, “I love it, I love it. Great idea, great work.” For me, it's by far the most unique album I've heard.

So this album is coming out soon. Do you know what it's called?

Eclairer le Monde, which translates “Light the World.”

Fantastic, I see that Youssou is playing at King's Theater in Brooklyn on April 27.

Yes, and he's gonna be in New Orleans doing the Jazz Fest.

Well, thanks, man. This is an excellent interview. Lots of meat here.

Yeah, man, you know, Afropop Worldwide, I'll forever say this story. If it was not for hearing this show, at the age of nine, 10, I wouldn't know who Youssou was. I would have known Ghanaian artists, but it was this show that taught me about two of the main people I've worked with and have relationships with now, Youssou N’Dour and Baaba Maal. Because of this show.

That's a great testimonial.

So I'm forever a fan of this show. As long as I’ve got breath in my voice, as long as I have a spirit to speak, I will fight for this show. I will fight.

God bless you, Weedie. Travel safely.

Related Audio Programs